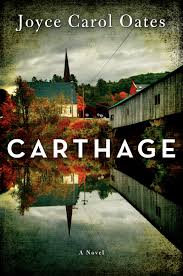

Carthage by Joyce Carol Oates

To Carthage then I came

Burning burning burning burning

O Lord Thou pluckest me out

O Lord Thou pluckest

burning

(T. S. Eliot The Waste Land)

It still amazes me, how critics still seem not to ‘get’ Joyce Carol Oates, how often her prodigious talent is spoken of dismissively, in belittling terms – ‘oh, Joyce Carol Oates, there’s just so much of it!’ – as if her very prodigiousness, the prolific expression of her talent could be a reason to reject it as something freakish and therefore unworthy in some way.

It still amazes me, how critics still seem not to ‘get’ Joyce Carol Oates, how often her prodigious talent is spoken of dismissively, in belittling terms – ‘oh, Joyce Carol Oates, there’s just so much of it!’ – as if her very prodigiousness, the prolific expression of her talent could be a reason to reject it as something freakish and therefore unworthy in some way.

‘She writes so much – is any of it any good?’

I’ve heard this said, seen it written. It often crosses my mind, and seems increasingly clear to me, that were Joyce Carol Oates a man her position as a ‘great American novelist’ would be assured. The broadsheets and the book blogs would all have been arguing over Carthage this summer instead of Purity. I wish they were. I wish they would. I think Oates is one of the greatest writers currently working, and I think that all the more because her books are not perfect. To me, each new novel (and I’ve probably read about half her output) feels like the next chapter, the next essay in an ongoing experiment, an ongoing project to discover the possibilities of the modern novel.

Some of these chapters are ragged, some are too long, some are just astounding. All are meant, involved, and acutely intelligent, the most complete expression of her intent the writer could manage at the time. All are worth reading, and all will stay with you, a quality which, surely, is one of the defining factors of great literature.

Fans of speculative fiction and horror in particular will be familiar with Oates’s interest in the gothic. Her most recent essay in the horror genre, 2013’s The Accursed, was a masterpiece of ambition and reach, spanning an American century, examining the guilt and tarnish at the heart of American privilege. I’ve written about the ‘Lovecraft chapter’ in The Accursed before, and it remains a shining memory. I don’t think I’ve yet mentioned the book’s sharp and canny mirroring of a perhaps-best-forgotten yet nonetheless fascinating horror novel of the 1970s, John Farris’s All Heads Turn When the Hunt Goes By, turning the embarrassingly misused tropes of that novel against each other, like wild dogs.

But Oates is just as interested in crime fiction as she is in horror, and it’s precisely novels like Carthage – ambiguous, labyrinthine, incautious, imprecise – that I’m forever bemoaning the scarcity of in the genre.

Some of those who care to examine Carthage as a work of crime fiction might be tempted to define it as one of those (always intriguing) works – Patricia Highsmith made a speciality of them – which pose as crime fiction but lack its defining element: that is, a crime. This is one way of looking at the book, but I would counter that Carthage is a story about a murder – just not the murder that is foregrounded.

The crime is fully described. A person is arrested and imprisoned. These two events are not connected in the way that they should be.

Carthage tells the story of Cressida Mayfield, a precocious and alienated nineteen-year-old who goes missing from her home in Carthage, upstate New York. We learn of the desperate search for this lost young woman, of the violence that appears to have precipitated her disappearance, the parents, the sister, the suspect (who happens to have been engaged to the sister), the half-truths and evasions, the blank spaces in memory and chronology that form the core material of such addictive mysteries. Fans of Oates will instantly be catapulted back to her earlier examination of this subject – the devastating impact of violent crime upon a previously stable and contented household – in her 1996 masterpiece We Were the Mulvaneys.

This first section of the novel is then cut off in mid-stream, with no resolution in sight. We tun the page and the jolt of unexpected revelation is physically palpable. What follows is strange, and much less easy to define: hundreds of pages of back-and-forth story. Gradually we learn everything, and perhaps more than we felt we needed to know, about Cressida Mayfield and what happened to her. The last people to find out what we have come to accept as the facts of the case are those most directly affected: those whose lives these facts have ripped apart.

I loved this book, even when I wasn’t loving it, even when I was wishing Oates would get to – or rather get back to – the point. I loved it because it is the kind of text that reminds readers that literature can aspire to be more than simply a pastime, an entertainment. That it should ask questions to which the answers are not always knowable or uncontested. That it should present itself in forms that can appear unfinished, as if the writer were still working on the manuscript up until the point where it needed to be delivered, still enmeshed in the world of those characters and the moral and psychological problems they represent.

Texts like these – where the writer’s engagement with the subject remains visible to the reader – I find to be amongst the most rewarding and significant.

I also found it odd, reading Carthage. There’s some stuff in it that overlaps, quite a bit, with what I’ve been writing myself these past eighteen months. I’ll never be Oates, of course, and the backgrounds of our work – American, British – are so very different. But I can’t help but feel that pulse of an interest simultaneously shared, a synchronicity that is disconcerting as much as it is satisfying.

Mainly though, I’m just left wanting to read more Oates.