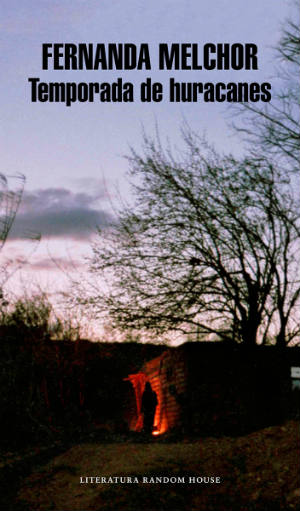

Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor translated by Sophie Hughes (2020)

“This is the story of a murder, but it’s not a murder mystery in any traditional sense.” (Sophie Hughes, Granta January 2020)

…and Brando felt himself choke with emotion, felt his skin prickle with goosebumps, and for a moment, with an almost cramp-like sensation in his gut, he wondered if maybe he hadn’t spat out the whole pill, if it was all just a hallucination, a strange nightmare, a bad trip brought on by bombing too much cheap aguardiente, by smoking too much weed and spending too long cooped up in that horrible house with that crazy terrifying bitch. He never told anyone how much Luismi’s voice had moved him, and he would rather have died than admit that the real reason he kept going to the Witch’s parties was to hear Luismi sing.

In the rural Mexican township of La Matosa, a murder has been committed. The body of the Witch, a person locally notorious for her occult powers and for the treasure she has supposedly been hoarding in her crumbling mansion, has been discovered submerged beneath the filthy waters of an irrigation canal. The police are summoned but no one will admit to knowing anything and in any case, this is not a story about a police investigation. What we get instead is less clear cut and more stubbornly resistant to judgement. Melchor’s characters tell their own tales, sometimes conflicting, sometimes overlapping. Sentences sprawl over several pages, unspooling in a welter of fury and pathos and technicolor profanity. By the end, we will know what happened, yet there is little sense of closure. The violence that led to the Witch’s murder will not blow itself out along with the hurricane. Rather it is a manifestation of the despair that is the inheritance of these deprived communities, a witch’s curse.

The best way to engage with this book is to give yourself up to it completely. As with Ariana Harwicz’s Die, My Love and Feebleminded, both of which I read last year, I found the only way I could fully appreciate the beauty, the madness and the pure technical mastery of Hurricane Season was to immerse myself in the text for an hour or more at a stretch, letting myself become prey to its rhythms, its structure, its firebomb language. I saw a review somewhere that likened the novel’s structure to that of Christopher Nolan’s film Memento, in which the time stream works backwards from the murder to its origins, and I thought that an insightful comparison. A second, perhaps inevitable parallel can be drawn with Kurosawa’s Rashomon. You might start this book wondering what is going on, who these people are and how they relate to one another. I would encourage you to keep going. The more you read, the more matters clarify, and – as with any more conventional detective story – there is much satisfaction to be gained from seeing the crime in context, to solving the terrible mystery of how and why it happened.

… and just then his telephone buzzed again and, once again, it was the kid, now telling him that he’d got hold of some cash, that he’d spot Munra’s petrol if he did him this one solid of taking him to a job, by which the witness understood that his stepson had required the services of taking him to a specified location where he could obtain the money to continue drinking, a proposal the witness accepted, meaning that inside his closed-top Lumina van (colour grey-blue, model 1991, with vehicle registration plates from the state of Texas roger, golf, X-ray, 511), he drove to the agreed-upon meeting point, namely, a row of benches in the park facing the Palacio Municipal de Villa, where he met his stepson, who was accompanied by two subjects, one of whom was known by the nickname of Willy, occupation VHS retailer in Villa market, roughly thirty-five to forty years of age, long black greying hair, dressed in his customary rock-band T-shirt and black combat boots…

In the fourth part of Roberto Bolano’s monumental 2004 novel 2666, Bolano details the deaths of 112 Mexican women that took place in and around Ciudad Juarez in the 1990s. The women were almost all from working class backgrounds, and heavily exploited. The police had notoriously little success in solving these murders or bringing anyone to justice. Hurricane Season can be read almost as an extra, previously missing chapter of 2666, a companion piece in which the backstories of some of the victims are explored in detail. As with Bolano, part of the power of Melchor’s writing resides in how un-polemical it is, at least outwardly. In asking her readers not to look away from the facts of this case, she reveals the murky no-man’s-land between good and evil. In acknowledging the inspiration given to her by journalists working on the front line of investigative reporting, she reminds us of the sometimes terrible cost of telling these stories in the real world.

Hurricane Season is one of those books you start out feeling frustrated with and end up being changed by. The moment I finished reading, I looped back round to the beginning of the book, sure in the knowledge that every word and connection that might have escaped me first time around would now be revealed in all its deadly clarity. What a rewarding, provoking, enriching, death-defying firestorm of a book this is. I feel privileged to have read it. For anyone looking for a crime story that does not shy away from the true nature of violence and its consequences, that refuses detective fiction’s reassuring archetypes in favour of something more challenging, more formally ambitious and more profound, I would recommend Hurricane Season unreservedly.