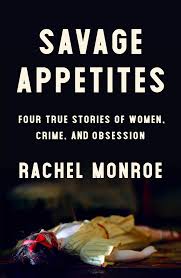

Savage Appetites by Rachel Monroe (2019)

Detective stories make good reading material for misfits. They teach you that being overlooked can be an advantage, that when your perspective is slightly askew from the mainstream, you notice things that other people don’t. If you imagine yourself as an investigator, you have an excuse to hover outside the social circle, watching its dynamics unfold. You’re untouched and you’re untouchable. Your weirdness becomes a kind of superpower.

I don’t have enough good things to say about this book. I’d go so far as to say that Savage Appetites is a book that everyone with an interest in true crime should read. As compelling as any novel, Monroe’s examination of the true crime phenomenon and in particular its attraction for women is as personal as it is forensic, as immersive as it is questioning. I’m not normally in the habit of marking up my books, but by the time I’d finished reading, my copy of Savage Appetites was peppered with little stars and underlinings. I loved this book unreservedly. I emerged from it feeling energised and inspired.

Monroe begins her documentary experiment with a simple yet immediately intriguing thesis. The women who find themselves attracted to true crime (be it books, podcasts, or documentaries – usually it’s all three) tend to fall into four broad groups: the detective (those who enjoy the investigative process and the sense of knowing that comes with it), the victim (those who feel an affinity with and want to draw attention to victims’ untold stories through possible parallels with their own lives), the defender (those with a powerful sense of justice who want to see justice done), and more disturbingly the killer (those who see aspects of themselves reflected in the marginalised, alienated and socially inadequate individuals who have committed murder).

Each of the four main parts of Savage Appetites is devoted to an individual or set of individuals who exemplifies their category. In the case of the detective, Monroe investigates the life of Frances Glessner Lee, the creator of the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death and dubbed by some as the mother of forensic medicine. In the victim category we meet Lisa Statman, an assistant film director whose fascination with Sharon Tate became so obsessive she moved into the guesthouse behind the infamous ‘murder house’ on Cielo Drive. This chapter is particularly insightful on the subject of the changes in attitudes towards crime that saw themselves enacted in the US prison system through the 1980s and through to the present day:

Studies of victimization find over and over again how similar victims and perpetrators are, but in the new rhetoric of victimhood, the world was divided up more neatly. A community of actual and potential victims, ‘us’, was pitted against actual and potential offenders, ‘them,’ a division along lines that were far from arbitrary… Crime isn’t worse, but it feels worse. Something feels worse, at least. It’s not that hard to imagine how such a thing might happen. How, if your world felt as if it were changing underneath your feet, if your life felt precarious and out of your control, and then you heard a good story that explained why that was, a story that placed the blame on a clearly defined bad guy, and then you kept hearing that story over and over, it might indeed begin to seem true.

The theme of law enforcement and its increasing politicisation continues in the third part of the book, which examines the notorious West Memphis Three case from the point of view of Lorri Davis, the woman who became so affected by the miscarriage of justice against Damien Echols that she turned over her whole life to the fight for a retrial. It’s an unusual and electrifying story, not least because stories like it, in which women devote themselves entirely to the cause of a ‘wronged man’ so often turn out badly, not least for the woman. In Lorri’s case, Monroe paints a portrait of an unusual and driven individual without shirking away from the emotional and psychological damage still inherent in her situation. The vast folly of America’s ‘Satanic Panic’ and the injustices it perpetrated still chills the blood – and also reminds us that we had our own version of this damaging episode here in the UK.

The most disturbing chapter deals with the subject of online serial and spree killer ‘fandom’, channeled through the bizarre fantasies of Ayn Rand and the case of Lisa Souvannarath and her failed plan to instigate a mass shooting. Monroe is brilliant and unsparing in her analysis of online fringe communities (such as the ‘Columbiners’), their possible motivations and insidious rhetoric as well as questions around gun control and increased surveillance. It is in this part of the book that Monroe interrogates herself most keenly, examining her own abiding fascination with true crime narratives:

Perhaps part of me felt as though I should have been [on trial]. I couldn’t stop thinking about how I, like Lindsay, had internalized the idea that murderers were fascinating. Over the years I’ve read thousands of pages about various varieties of Killer (Zodiac, Green River, BTK, Lonely Hearts) and Strangler (Hillside, Boston); don’t even get me started on the time I’ve devoted to goofy little Charlie Manson. My brothers can have entire conversations where they’re just tossing sports statistics back and forth; certain friends and I can do the same thing with serial murderers.

She chooses – rightly, I think – to end her study on a positive note, however:

Sensational crime stories can have an anesthetizing effect… but we don’t have to use them to turn our brains off. Instead, we can use them as opportunities to be more honest about our appetites – and curious about them, too. I want us to wonder what stories we’re most hungry for, and why; to consider what forms our fears take; and to ask ourselves whose pain we still look away from.

Rachel Monroe is one of a number of incredible true crime writers and investigative journalists – Sarah Weinman, Emma Eisenberg – who also happen to be women. Together, they’re helping to move true crime writing in a bold new direction, interrogating their subjects even as they report them. Asking us why we read what we read, why we are interested. I reiterate that I cannot recommend Savage Appetites highly enough, and needless to say I’m already hungry for whatever Rachel Monroe writes next.

(Oh, and in case you’re wondering, I’m classic Detective.)