The shortlist for the Women’s Prize for Fiction was announced this morning, and what a strong shortlist it is. I’ve already written about Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire, which remains potent in the memory as much for what it does with form as for its urgent storyline. Elif Batuman’s The Idiot is the book I most want to read next. I adore Batuman’s essays, and her memoir about Russian literature, The Possessed, is a thing of rapturous beauty. Jessie Greengrass’s Sight is also high on my list, not least because of the contradictory reactions it’s been garnering. The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock and Sing, Unburied, Sing have been outliers for me up till now, but I’m planning to read both before the winner is announced, if I possibly can.

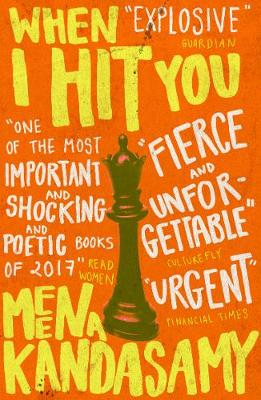

The novel I want to comment on today though is Meena Kandasamy’s When I Hit You: Or, Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife. If I read a more important book this year, I will be surprised. People have been describing this novel as a memoir of domestic abuse, which it is, but such a bald description fails to convey the majesty of all that is in it. If I were forced to use one word to describe When I Hit You it would be triumphant. It is a triumph not just in terms of victory of the spirit, but in terms of the writing art. The very act of writing – the act that most enrages the narrator’s solipsistic, jealous, controlling, abusive and above all selfish, selfish, selfish husband – is celebrated in these pages to the absolute utmost. Indeed, I cannot think of a better riposte, a sweeter revenge for the violence the narrator has suffered than this excoriating, empowering book about womanhood and violence, art, the practice of sanity, language and freedom of expression. I cannot think of a book that would be a more worthy winner of the Women’s Prize than this vital, supremely intelligent text, superbly realised. Angry but never embittered, this is a novel every woman – and for fuck’s sake, every man – needs to read as soon as they can.

The novel I want to comment on today though is Meena Kandasamy’s When I Hit You: Or, Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife. If I read a more important book this year, I will be surprised. People have been describing this novel as a memoir of domestic abuse, which it is, but such a bald description fails to convey the majesty of all that is in it. If I were forced to use one word to describe When I Hit You it would be triumphant. It is a triumph not just in terms of victory of the spirit, but in terms of the writing art. The very act of writing – the act that most enrages the narrator’s solipsistic, jealous, controlling, abusive and above all selfish, selfish, selfish husband – is celebrated in these pages to the absolute utmost. Indeed, I cannot think of a better riposte, a sweeter revenge for the violence the narrator has suffered than this excoriating, empowering book about womanhood and violence, art, the practice of sanity, language and freedom of expression. I cannot think of a book that would be a more worthy winner of the Women’s Prize than this vital, supremely intelligent text, superbly realised. Angry but never embittered, this is a novel every woman – and for fuck’s sake, every man – needs to read as soon as they can.

The thing that strikes me – and pleases me – most forcefully about this year’s Women’s Prize shortlist is its seriousness. These are books that are not afraid to take the personal and make it political. These are books that are not afraid of going in hard on big questions. These are authors that are unapologetic about their love of language, their joy in experimentation, their determination to be heard, their willingness to be difficult. It will be very interesting to see if any of these turn up on the Booker longlist, announced in July. Congratulations to all the writers, and also to the judges on the boldness and brilliance of their choices, on showing us why and how the Women’s Prize continues to be so important.