I’ve been thinking about this for a long time so I’m just going to say it: if Nicola Barker were a man, she would immediately become Significant, hailed as one of most exciting and innovative British writers of the postmodern era. As things stand, she is more usually sidelined into ‘quirky’, ‘whimsical’, ‘difficult’ or ‘depressing’. She has ‘a devoted cult following’, of course she does, and anyway, she was shortlisted for the Booker, so what does she have to moan about?

I’ve been thinking about this for a long time so I’m just going to say it: if Nicola Barker were a man, she would immediately become Significant, hailed as one of most exciting and innovative British writers of the postmodern era. As things stand, she is more usually sidelined into ‘quirky’, ‘whimsical’, ‘difficult’ or ‘depressing’. She has ‘a devoted cult following’, of course she does, and anyway, she was shortlisted for the Booker, so what does she have to moan about?

Why then is she still not discussed alongside Pynchon, Foer, Amis, Rushdie or even Mitchell? Barker’s oeuvre is remarkable in its depth of field, its social comment, its capacity for formal innovation. Her dialogue is incisive and brilliantly funny. The stories she tells offer an often excoriating commentary on the way we live now. Yet Barker is only ever discussed as an anomaly, a domestic comedian, an acquired taste. Why is this? The answer seems more depressingly clear with each new novel: women writers (still) aren’t expected to do this kind of stuff, so the narrative they get written into becomes subtly twisted.

“I know that piece.” The Stranger – Savannah – nodded towards ****, but his eyes remained fixed on me. “There are three parts to it. The Prelude was written long after the other two movements, but now it sits at the start. It is wistful, melancholy. There are bells ringing throughout. And an organ plays Bach. The composer – Augustin Barrios – was of indigenous blood. A great Romantic. A genius.”

“He died, in poverty, of syphilis,” **** sneered. “What possible romance is there in that?”

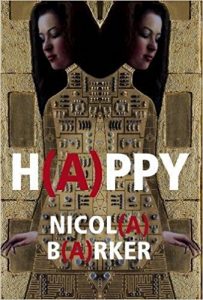

Nicola Barker’s new novel H(A)PPY is remarkable in many ways. The dystopia it portrays is all the more chilling because it is presented as a utopia: there are no mass killings, no persecution, no banned books. All that is understood to be in the past. The social coercion that exists – to be perfect, to be happy, to discard the depressing march of history in favour of universal progress – exists because it has been chosen, because people accede to it willingly. No one is hungry, confused or in need. For Mira A, her desire to find out about a particular figure from the past – the Paraguayan musician and composer Augustin Barrios – is dangerous only in that it throws her preconceptions – her notion of happiness – into doubt. Like turning back the corner of a rug to reveal the dirty floor beneath, one small revelation can lead to a greater, more far reaching revelation that has huge implications. So it is for Mira A. So it is with H(A)PPY. So it is for the question over the reception of Barker’s writing.

In H(A)PPY, even the choice of the guitarist as hero is significant. The guitar has often been looked down upon as a folk instrument, an instrument lacking in subtlety, flexibility or repertoire, insignificant precisely because of its accessibility. The great novels of music have tended to place their focus upon the piano or the violin – glamorous and complicated, the instruments of record for tortured, glamorous, misunderstood males. Barker’s choice of the guitar – available to everyone, easily portable, a ready accompaniment and partner to the human voice, the natural instrument of protest – is in itself an act of rebellion, a way of smuggling subversive ideas between the cracks of cultural orthodoxy.

I scowl and turn again to the native – the performer – the patriot – the humiliation – the farce. Which of these two should I address? I wonder. Which do I prefer? Both are unreal. Both have been so carefully, so painstakingly constructed. Can these two – the one so civilised, so polite, so careful: the other so fearless and ridiculous and romantic – be merely one entity? Is that feasible? How might I conceivably hope to address them when I am not even able to unite them successfully within my own consciousness.

The native Barrios sits down on a pew and begins to play. The kneeling Barrios covers his ears.

Here Barker illuminates the duality of Barrios, a natural genius forced to adopt Western models of excellence in order to be taken seriously as a composer, whilst simultaneously being driven to perform his nationality in order to enhance his stage persona. As she is drawn to examine Barrios’s inner conflict in greater depth, so Mira A discovers a similarly corrosive dichotomy within herself.

H(A)PPY addresses Barker’s recurring concerns – class, celebrity, capitalism, the slippery, explosive power of the written word – whilst also exploring questions of power inequalities between citizens and state, Western nations and indigenous peoples. I found in H(A)PPY some of the same quietly oppressive quality that characterises Karin Tidbeck’s Amatka, a chilling vision of the alternate near future that is all the more effective for being so understated.

As science fiction, H(A)PPY is brilliant: inventive and thought provoking and unlike anything you’ll have read so far this year. In the games it plays with scrambled fonts and typographic art, you will probably be reminded of Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves, always a good thing in my book. Barker recommends reading H(A)PPY whilst listening to the music of Barrios, a ploy some might dismiss as a gimmick but that I would go along with, one hundred percent. In fact it’s a shame the publisher couldn’t have gone the extra mile and included a CD recording tucked into the back flap. Luckily you don’t have to search far to find what you’re looking for. As a novel about music, H(A)PPY is one of the most imaginative and powerful I’ve ever read.

In many ways, this is the novel I wanted Joanna Kavenna’s A Field Guide to Reality to be. H(A)PPY is more successful for me as science fiction through being more explicit, and Barker’s writing about Augustin Barrios was never not going to resonate. I love this book. I think Nicola Barker is a genius. Should H(A)PPY end up on the Clarke shortlist in 2018? Hell, yes.