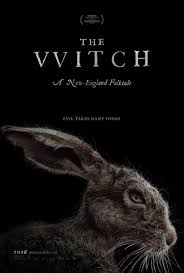

Well, this was interesting. I’d been looking forward to The Witch ever since seeing the trailer around this time last year. I missed seeing it in the cinema but finally caught up with it on DVD, a perfectly acceptable substitute when the need arises, but the unnerving, subtle beauty of the cinematography did leave me wishing I’d been able to experience this movie on the big screen as the director intended.

Well, this was interesting. I’d been looking forward to The Witch ever since seeing the trailer around this time last year. I missed seeing it in the cinema but finally caught up with it on DVD, a perfectly acceptable substitute when the need arises, but the unnerving, subtle beauty of the cinematography did leave me wishing I’d been able to experience this movie on the big screen as the director intended.

Cast out from their fledgling Puritan community in the backwoods of seventeenth-century New England (the film opens with a theological disagreement between church elders) William (Ralph Ineson getting his best Nedd Stark on) and Katherine (the always excellent Kate Dickie) take their five children to live in a remote farmstead on the edge of the forest. When the youngest of the children vanishes without a trace, William is determined to blame the tragedy on blind chance – a wolf must have taken the boy. Twins Jonas and Mercy have other ideas, though – everyone knows the woods are home to witches. Their brother’s disappearance must surely be the work of the devil. But who is the devil working through, and who will be his next victim?

It would be impossible to watch the first half of this film without thinking of Nicholas Hytner’s The Crucible, with Ralph Ineson in the Daniel Day Lewis role, a man of faith who is nonetheless determined to uphold the laws of reason in the face of a religious extremism that threatens to overturn the community and civilisation they have spent so long in building. Naturally blame for the devilish goings on is laid at the door of Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy), William and Katherine’s adolescent daughter whose burgeoning sexuality has already begun to stir the senses of her younger brother Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw). William won’t have it, though – Thomasin is ‘his girl’, intelligent, truthful and responsible. When she says the twins’ talk of her being a witch is nothing but a joke, he is prepared to believe her. But as tragedy after tragedy strikes the family, his faith in God and in his daughter is tested to the limit – and beyond.

As with The Crucible, it is emotional claustrophobia, the sense of creeping entrapment with no safe way out for anyone, that defines the action of this unusual and affecting film. The family, already under a severe strain from the harsh demands of their environment, seem besieged by misfortune, and the rising tide of horror seems all the more unbearable for taking place in such isolation, away from the sight and knowledge of anyone who might offer help. Of course it’s more or less impossible to know what life in a seventeenth-century New England village might ‘really’ have been like, but the period details here – the robust Puritan clothing, the mud, the candlelight, the sinister, encroaching forest and above all the sense of being acutely vulnerable in a vast and unknowable world, are rendered with a level of passionate commitment (I was reminded of Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights) that makes them feel accurate and utterly convincing.

What surprised me most about The Witch was the ultimate direction it chose to take. I don’t want to spoil the film for anyone by revealing too much about that, and even hours after seeing it I still can’t decide whether it was madness to go that way, or genius. What I do know is that The Witch is a beautifully crafted, richly imagined and intellectually worthwhile addition to your watch lists, and I would advise any fan of horror cinema – especially quiet horror cinema – to see this as soon as you can, if you haven’t already.

There’s a fascinating and informative interview with the film’s director, Robert Eggers, here. Suffice it to say this guy has definitely earned his horror credentials!