“I had believed in fiction as a uniquely powerful way of speaking the truth about experience. I had believed that it was, like art in general, necessary, and that a society with no interest in reading serious fiction (serious meaning done with care, with love) was in some way damaged or on its way to being so. None of that, I realised, had really changed. What I had believed at 17 I still, by and large, thought true. But now there was something else going on, a chilly countercurrent, a hard-to-pin-down sense of frustration that seemed to organise itself around the idea that fiction – in novels, in films, on television – had become more competent than interesting, more decorative than urgent, more conventional than otherwise. I picked up novels and put them down again. They were not badly written, not at all, but after a page or two I felt I knew them, knew what, at the deeper level, they were up to. I slid off their surfaces. I struggled to care. I had precisely the same difficulty with my own work. Projects started; projects abandoned. Was this writer’s block? Or was it a hazy recognition that there might be some problem with “traditional narrative”? A set of assumptions that had become almost invisible but that shaped what we wrote?”

“I had believed in fiction as a uniquely powerful way of speaking the truth about experience. I had believed that it was, like art in general, necessary, and that a society with no interest in reading serious fiction (serious meaning done with care, with love) was in some way damaged or on its way to being so. None of that, I realised, had really changed. What I had believed at 17 I still, by and large, thought true. But now there was something else going on, a chilly countercurrent, a hard-to-pin-down sense of frustration that seemed to organise itself around the idea that fiction – in novels, in films, on television – had become more competent than interesting, more decorative than urgent, more conventional than otherwise. I picked up novels and put them down again. They were not badly written, not at all, but after a page or two I felt I knew them, knew what, at the deeper level, they were up to. I slid off their surfaces. I struggled to care. I had precisely the same difficulty with my own work. Projects started; projects abandoned. Was this writer’s block? Or was it a hazy recognition that there might be some problem with “traditional narrative”? A set of assumptions that had become almost invisible but that shaped what we wrote?”

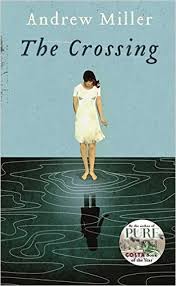

In a fascinating piece in The Guardian, novelist Andrew Miller writes about the problem of fiction in a way that is striking a particularly resonant chord with me right now. Is the manufactured, anodyne quality of so much of today’s fiction in some way a mirror to the political situation in which we now find ourselves? The literature of disengagement ultimately signalling a crisis-of-everything? These are some of the questions I’m thinking about – along with are we now reaching the end of the current political era? I will certainly be reading Andrew Miller’s latest novel, The Crossing, which sounds pretty special and if it gets a good review from Kate Clanchy – who never pulls her punches – then that’s good enough for me.