This year marks the 300th anniversary of the publication of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, the work that is generally proclaimed as the first English novel. To mark this tricentenary, the BBC is launching a major new TV series exploring the phenomenon of the novel and the impact this art form has had, on our imaginative lives as individuals and on our development as a society. As part of its year-long celebrations, the BBC invited a panel of six well known writers and cultural commentators – Stig Abell, Syima Aslam, Juno Dawson, Kit de Waal, Mariella Frostrup and Alexander McCall Smith – to assemble a list of one hundred English-language novels they feel have exerted a major impact – both on them personally, and on our cultural life as a nation.

“We asked our prestigious panel to create a list of world-changing novels that would be provocative, spark debate and inspire curiosity,” explains Jonty Claypole, the director of BBC Arts. “It took months of enthusiastic debate and they have not disappointed. There are neglected masterpieces, irresistible romps as well as much-loved classics. It is a more diverse list than any I have seen before, recognising the extent to which the English language novel is an art form embraced way beyond British shores.”

A very conscious attempt to challenge the canon, then, which is much to be applauded. The list certainly encourages debate – there are titles here that almost everyone will agree on rubbing shoulders with titles that will leave some critics rolling their eyes and tutting about standards. This is all part of the fun of the thing, of course – and I’m greatly looking forward to all the upcoming documentaries, discussion programmes and author profiles the BBC is promising us.

The whole business has got me thinking, though, about the impossibility of assembling a list that will have meaning for everyone. The panellists have helpfully arranged their choices into ten broad categories: Coming of Age, Love and Romance, Crime and Conflict, Politics, Power and Protest, Identity, Adventure, Family and Friendship, Class and Society, Life, Death and Other Worlds and, tantalisingly, Rule-Breakers. It’s as good a way of organising one’s thoughts as any, but reading is, above all, personal, and so it is inevitable that everyone who encounters this list will respond with more enthusiasm to some categories than others.

There is also the perennially vexed question of how you choose, what criteria come into play when making selections. It would seem obvious that anyone compiling such a list as part of a curriculum for a course of study, say, or curating an anthology, or indeed setting down a framework for a BBC Arts series has a duty to be as wide-ranging and representative as possible. We would want such a list to encompass the novel across all periods in its development. We should also demand that such a list be inclusive – of women writers, LGBTQ+ writers, writers from diverse social, cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Lists that fail to be inclusive will – directly or indirectly – help to shore up existing boundaries and biases, leading to a lopsided, restrictive view of literature and the potential alienation of millions of new readers and writers.

If we are choosing just for ourselves, though, our choices will naturally reflect our personal biases, our life experiences as readers, and I would argue that this is a tendency that should not be stifled but actively celebrated. If I were to find myself perusing a list of Hilary Mantel’s favourite books, or Nicola Barker’s, or Will Self’s, I would want to get a genuine insight into their thought processes and working methods, their personal literary canon. The books that made them writers, in other words. I would not be nearly as interested in seeing a list of titles they believe might make them look politically acceptable, intellectually on trend, or – heaven forbid – a nice person. I want to get at the meat.

There is huge value in group discussions of what literature represents and who it is representing. When I look back at how my own reading might have been shaped by such discussions – or lack of them – within the British education system I find myself interested and disturbed in equal measure. But there is also value in individual response, in laying bare our personal proclivities and blind spots, the ragged and digressive path of our creative development. In examining our choices, we offer ourselves the opportunity for reflection, and, perhaps, change. In looking at what is important to us now, we begin to wonder what might be more important to us in ten years’ time.

So in celebrating the tricentenary of Robinson Crusoe, I’m suggesting we all get naked! Here below you will find my own list – not of novels that shaped our world necessarily, but of novels that irrevocably, unequivocally shaped MY world. My main criterion in assembling this list has been that anyone reading it should be able to tell a lot, maybe everything, about who I am as a writer, how my literary interests have developed and what makes me tick. The one rule I set for myself was that no author could be represented on the list more than once. My selection parameters differ slightly from those of the BBC panel in that I have included works in translation. Novels written in languages other than English have been so central to my life and to my thinking that a list that did not include them would be practically meaningless. In similarly cheating vein, I have also included two poetry collections, and three short fiction collections. In the case of the Eliot and the Plath, these works have been so central to my literary outlook that leaving them off would feel like a lie. In the case of Oyeyemi and Wood, I wanted both these authors to be on my list, and these happen to be my favourite works by them. In the case of the Williams, her debut novel isn’t out yet and her collection Attrib. is too important to me not to be included.

In the case of the four series I’ve included, it’s simple tit for tat: if the BBC can have the whole of Harry Potter, I can have the Tripods.

After careful thought, I decided that rather than arranging my list alphabetically I would list the books chronologically, that is, the order in which I personally first encountered them. I cannot be one-hundred percent accurate about this – I no longer remember if I read Picnic at Hanging Rock before The Turn of the Screw or vice versa – but it’s as close to the truth as I can get. There are also authors I read other works from before the one cited – I read Ian McEwan’s The Cement Garden when I was fourteen, for example, well over a decade before Enduring Love, but it’s the later novel that has left the most lasting impression, and so that’s the one I’ve chosen.

The earliest book cited here forms one of very first reading memories and my heart still clenches every time I see the cover. The most recent, I haven’t quite finished yet but I know already that it’s a keeper. Are there books I feel sad not to have included? Dozens.

It’s been a fascinating list to compile. One of the things that pleases me most about it is that it includes only two books – the scintillating and important Wide Sargasso Sea, the seminal Nineteen Eighty-Four – that happen to coincide with those selected by the BBC panel. Which only goes to show how individual a passion reading is, how many game-chamging, groundbreaking masterpieces we have to choose from, and be inspired by.

100 NOVELS THAT SHAPED MY WORLD

Borka: the Adventures of a Goose with No

Feathers

by John Burningham

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl

Stig of the Dump by Clive King

Charlotte Sometimes by Penelope

Farmer

Thursday’s Child by Noel

Streatfield

‘Adventure’ series by Willard

Price

The Ogre Downstairs by Diana Wynne

Jones

Carrie’s War by Nina Bawden

Jane Eyre by Charlotte

Bronte

The Time Machine by H. G. Wells

‘UNEXA’ series by Hugh Walters

Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

‘Changes’ trilogy by Peter

Dickinson

‘Tripods’ trilogy by John

Christopher

The Dolls’ House by Rumer Godden

The Chrysalids by John Wyndham

Watership Down by Richard

Adams

The Magician’s Nephew by C. S. Lewis

My Cousin Rachel by Daphne Du

Maurier

All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque

A Passage to India by E. M. Forster

The Old Wives’ Tale by Arnold Bennett

Nineteen Eighty-Four by George

Orwell

Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy

Pavane by Keith Roberts

Roadside Picnic by Arkady and

Boris Strugatsky

The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot

Ariel by Sylvia Plath

The Grass is Singing by Doris

Lessing

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

The Drought by J. G.

Ballard

Doctor Zhivago by Boris

Pasternak

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

The Search for Christa T. by Christa Wolf

The Idiot by Fyodor

Dostoevsky

Doktor Faustus by Thomas Mann

Ada by Vladimir Nabokov

The Turn of the Screw by Henry James

Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay

The Book and the Brotherhood by Iris Murdoch

Strangers on a Train by Patricia

Highsmith

The Affirmation by Christopher

Priest

Midnight Sun by Ramsey

Campbell

Ghost Story by Peter Straub

The Brimstone Wedding by Barbara Vine

The Course of the Heart by M. John

Harrison

Enduring Love by Ian McEwan

The Blind Assassin by Margaret

Atwood

Personality by Andrew

O’Hagan

House of Leaves by Mark Z.

Danielewski

The Gunslinger by Stephen King

The Iron Dragon’s Daughter by Michael

Swanwick

The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe

Shroud/Eclipse by John

Banville

My Tango with Barbara Strozzi by Russell

Hoban

The Green Man by Kingsley

Amis

The Sheltering Sky by Paul Bowles

Cloud Atlas by David

Mitchell

Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel

Shriek: an afterword by Jeff VanderMeer

Austerlitz by W. G. Sebald

Darkmans by Nicola

Barker

Glister by John

Burnside

The Good Soldier by Ford Madox

Ford

The Kills by Richard

House

A Russian Novel by Emmanuel

Carrère

The Third Reich by Roberto

Bolano

The Dry Salvages by Caitlin R.

Kiernan

In the Shape of a Boar by Lawrence

Norfolk

The Lazarus Project by Aleksandar

Hemon

The Accidental by Ali Smith

Happy Like Murderers by Gordon Burn

F by Daniel Kehlmann

Straggletaggle by J. M.

McDermott

The Lost Daughter by Elena

Ferrante

What is Not Yours is Not Yours by Helen Oyeyemi

The Loser by Thomas

Bernhard

The Peppered Moth by Margaret

Drabble

All Those Vanished Engines by Paul Park

Sorcerer of the Wildeeps by Kai Ashante

Wilson

The Infatuations by Javier

Marias

Outline by Rachel Cusk

A Separation by Katie

Kitamura

Satin Island by Tom McCarthy

Carthage by Joyce Carol

Oates

This is Memorial Device by David Keenan

The Sellout by Paul Beatty

Death of a Murderer by Rupert

Thomson

Lanark by Alasdair Gray

Falling Man by Don DeLillo

Dept of Speculation by Jenny Offill

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor

Attrib. by Eley

Williams

Berg by Ann Quin

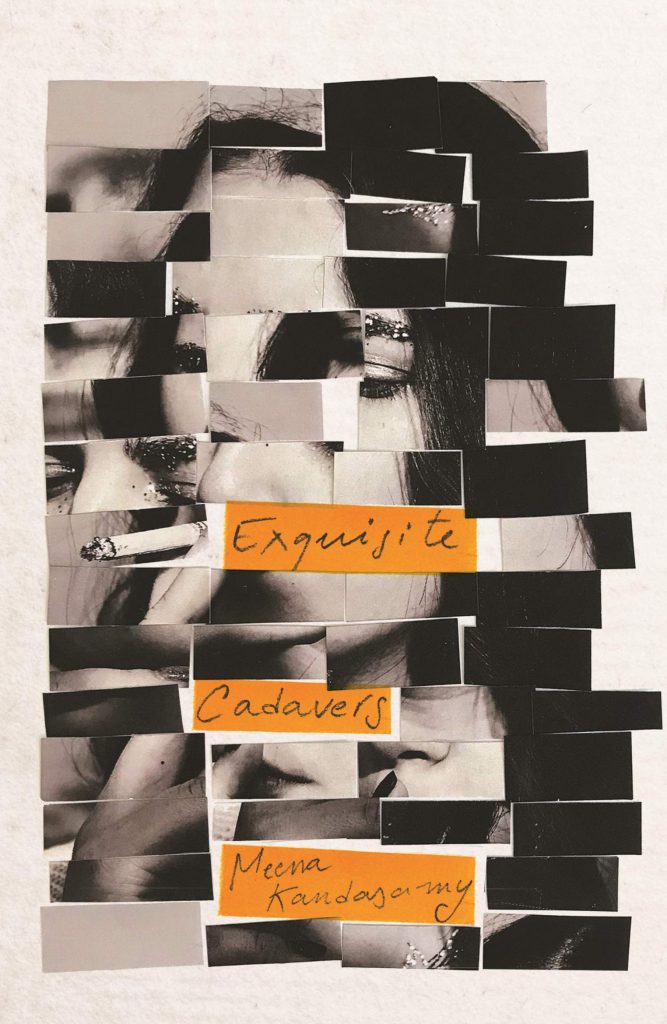

When I Hit You by Meena Kandasamy

Munich Airport by Greg Baxter

Caroline’s Bikini by Kirsty Gunn

Die, My Love by Ariana

Harwicz

The Sing of the Shore by Lucy Wood

Flights by Olga

Tokarczuk