….. can now be read at the Featured Story page. A summer story this one, so only fitting for the time of year. ‘Microcosmos’ was originally published in Interzone #222.

Month: July 2011

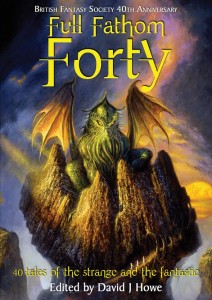

The British Fantasy Society is forty years old this year, and to celebrate, the current chair David Howe has been busy putting together a mammoth forty-story anthology entitled Full Fathom Forty. The book will be launched at this year’s FantasyCon in Brighton. I was surprised and delighted to find one of my own stories, ‘Feet of Clay,’ selected as part of the line-up.

‘Feet of Clay,’ which was originally published last year in the anthology Never Again, edited by Joel Lane and Allyson Bird, had a curious – not to say panic-stricken – genesis. Joel and Ally’s brief was simple: they wanted stories that expressed an opposition to fascism or any other form of racism or hate crime. Not a difficult sentiment to express, you might have thought, and I also believed I had my submission all worked out. As an older child and young adult I adored dystopian fiction. The strong anti-totalitarian message contained in such novels as Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four, Zamyatin’s We, Huxley’s Brave New World and Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day was a positive reinforcement to the idealistic left-wing politics I was dabbling in back then, and I loved the skilfully cadenced call to revolution these stories inspired. The mixture of SF and politics was driving and compelling. More subtle explorations of these themes – Keith Roberts’s magnificent Pavane and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids (possibly my favourite book then and still my favourite Wyndham to this day) made me even more of an addict.

The book that changed everything for me, in a political sense most immediately but in a more far-reaching artistic sense also was Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. It slapped my innocent face with its experience, stunned me with its tensely fought counter-arguments to exactly those questions I had been so devotedly pondering, and – most of all and most importantly – thrilled me with its radical and decidedly European style of engagement with the issues that mattered most to me: freedom of expression and the freedom to decide one’s own fate. What it also showed me – like Orwell’s great novel before it – was how political argument could be voiced in terms of a moving and compelling drama of the emotions.

(It’s a far cry from Chernyshevsky, believe me…… )

What stuck – and sticks – most about the Koestler was its ambiguity. When art is employed in the service of politics of whatever stripe, a dangerous game is being played – dangerous for the politicians (hopefully) and for the artist (certainly). No writer of any worth can ever place himself wholly and one-hundred percent in allegiance with any one party – if he does he’ll find he’s doomed as a writer. For me the ‘simple’ task of writing a story ‘against’ fascism turned out to be hideously difficult. The most obvious pitfall was cliche – it’s all been done before and so much better. Close behind it came the slipperiness of the arguments, the elusiveness of the ‘enemy’ himself: was the death of Heydrich worth the destruction of Lidice? Certainly not. The most obvious means of fighting oppression are rarely the cleverest.

I had decided the best thing to do would be to try my hand at precisely that kind of dystopian tale that had so caught my imagination when I was younger. I took a fragment of something I had tried to write a year or so earlier and turned it into what eventually became ‘The Silver Wind.’ A disastrous decision as it turned out, because Ally and Joel wanted stories of 6,000 words or less; ‘The Silver Wind’ came in at 16,000.

At that point I had precisely two weeks left to meet the deadline. I like to have at least a month to work on a story, and I was in a right panic. In a desperate effort to pull something out of the bag I tried something I’d never attempted before, and wrote the story outwards from the centre. The central scene I had in mind at least was clear to me: a father and a daughter, exploring the hills of the Derbyshire Peak District and talking about a death in the family. That was all I knew at that point, but once I got Jonas and Allis having their conversation it came together. The story even manages to make some points about fascism: not just the horror of its more outrageous crimes, but the insidious ambiguity of its legacy, the Midas-like toxicity of any form of violence, in whoever’s name.

Reading the proofs of the story for Full Fathom Forty I experienced that surge of surprise you occasionally get as a writer when you come upon your work unawares. It was more than a year since I wrote ‘Feet of Clay,’ and I felt glad I had written it.

If the ToC for Full Fathom Forty is anything to go by, this promises to be a book packed with variety and surprise, a genuine ‘snapshot’ of the face of British fantasy in 2011. The only story in the book (apart from my own) that I’ve read thus far is the Rob Shearman, brilliant and brilliantly original as always. The rest I shall have to look forward to along with the rest of you.

For those of you not coming to Brighton, you can pre-order a copy of FFF here

It’s hard to focus on anything fully when you’re caught up in the maelstrom of moving house, one of my least favourite activities in the world, ever. It looks like we’re into the endgame now though, so my dreams of spending the second half of this year researching, planning and beginning actual written work on my new book may yet come to pass.

In the meantime, I’m pleased to report that I’ve completed the final draft of the new Martin story and the revisions of the earlier pieces in the set, and so my mini-collection The Silver Wind is now complete.

I’m happy with the way it turned out. Watch this space for publication details.

No sooner had I sent the ms off to David Rix at Eibonvale than I had an article on Robert Aickman to finish – that’ll be in next month’s issue of Starburst Magazine. It was a real rush to meet that deadline, but I can’t really complain, because reading and thinking about Aickman is a singular pleasure. His story ‘The Swords’ is just so damn brilliantly weird, and ‘Ringing the Changes’ holds – bizarrely perhaps – such happy memories for me because hearing the Jeremy Dyson radio adaptation in 2000 was my first ever encounter with Aickman’s work.

Currently indulging myself with Stephen King’s most recent clutch of novellas, Full Dark No Stars. That’s rare steak on the skillet perhaps after the refinements of Aickman, but by God that man can tell a story.

With so much dashing, rushing and packing it’s hard to believe that less than a fortnight ago Chris and I were in Paris……

I went to the ICA this evening, to see Jessica Oreck’s new (I say new, but looking at iMDb I see it was made in 2009 and has only just had its UK release) documentary feature Beetle Queen Conquers Tokyo. The film explores the intricate and intimate relationship between the Japanese people and….. beetles! I knew I had to see this film the minute I read about it, and that if I didn’t grab the chance this weekend I would miss it. Even in our enlightened metropolis, movies about buglife aren’t likely to be granted more than a half-dozen screenings.

Even I, one of the weird handful of people who would actively go out of their way to track down stuff like this, was unprepared for the extraordinary revelations this movie had to offer. Why dream of alien planets when right here on Earth we have a city where giant scarabs are as common a household pet as the hamster or gerbil, where crickets are invited into the home to provide live music, where the dragonfly is a symbol of bravery and the emblem of the warrior class?

In Toyko, you can go to the mall and pick up a new pair of jeans and a pair of Nikes, then pop into the store next door and buy a rainbow beetle and a pack of synthesized tree sap to feed him with. The amusement arcades are packed with kids playing computer simulations of Bug Hunt and Bug Wars. Adults and children set off at weekends into those patches of forest and wild places that still remain close to Tokyo to have a picnic and to track live insects.

Families gather at dusk to watch the fireflies. Our beetle seller from the mall proudly shows us the red Ferrari he bought with his earnings.

It is not just its content that makes this film extraordinary but the directorial vision that lies behind it. Beetle Queen appears to be Jessica Oreck’s first full-length feature, yet it speaks with the kind of self assurance that if not born of long experience can only come from a genuine and passionate commitment to its subject matter. It is not a conventional documentary. It is a work of impressionist art, a montage, a collage of ideas and images that leaves you feeling you’ve been granted a privileged glimpse into one artist’s unique methodology as well as the secret mechanisms of an entire culture.

The Tokyo of this film is a world of hidden allusions and complex symbolism, an environment we in the West have come to think of as the most intensively urbanised in the world and yet whose people still maintain their connection with nature in ways that make you re-evaluate everything you thought you knew about Japan. It made me think about my other most recent literary and filmic experiences of that country – David Mitchell’s Number9Dream, Gaspar Noe’s Enter the Void, Richard Lloyd Parry’s compelling book about the life and death of Lucie Blackman, People Who Eat Darkness – and what Beetle Queen had in common with all of these was the sense it carried that this is a world that we as Westerners can gaze upon but never fully enter. Unlikely though it may seem it was Noe’s film that kept coming to mind while I was watching Beetle Queen. The interplay of colour and light, the almost hallucinogenic swirl of sensory impressions, the interlocking grids of train-tracks, street intersections, city freeways that characterise both films, drawing you down into a mind-maze that both dazzles and disturbs.

In particular I was enchanted by the attitude of the children, girls and boys alike who treated their pet insects with respect and rapt wonderment, a small boy sillhouetted in the ultraviolet light of a moth trap, releasing a grey-green Lunar Moth back into the wild as a trainer might toss a racing pigeon into the sky, the three young friends who called their dung beetles ‘brothers.’ The idea that one should fear or loathe these creatures would, I suspect, be utterly alien to them.

After the film we were lucky enough to be given an impromptu and completely unadvertised talk by the Curator of Beetles at the Natural History Museum. His mini-lecture, sprinkled with phrases such as ‘the other day when we were in Peru,’ and ‘we’re in the course of naming this beetle after one of my colleagues,’ was sheer delight, all the more so given that he had brought several cases of beetles with him to illustrate it. These we were allowed to examine in close-up, and audience questions were not in short supply as a 20cm Amazonian beetle larva made its rounds among us in its jar of formaldehyde. ‘Careful with that,’ said our tame entomologist. ‘The lid’s loose.’

Which just goes to show, I suppose, that a love of beetles has very little respect for national boundaries. And according to the staff of the Natural History Museum, the number of girl coleopterists is on the rise.

I love this city.

Read an interview with Jessica Oreck here.

As the stories I write tend to adopt the weather conditions prevailing at the time they come into being, so they often become irredeemably associated with a certain album or piece of music. I must have listened to Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ concerto about thirty times when I was writing ‘The Muse of Copenhagen,’ five times in succession on some days. I can’t always have music playing when I am writing – if a first draft especially is proving difficult it is dangerously distracting – but while second-drafting it is a wonderful stimulus.

The odd thing about it is that it seems to be the stories themselves that guide my choice of music, that demand the concentrated absorption in certain pieces that only obsessively repeated listenings can bring. I’ve been working on the second draft of ‘Rewind’ this week, and the story will now be forever associated for me with The Harrow and the Harvest, the hypnotically sublime new album from the alt-country singer Gillian Welch.

Gillian Welch became famous when she guested on the soundtrack album of the Coen brothers’ O Brother Where Art Thou. She is an infamous perfectionist. Fans of her music have been waiting eight years for a new album – she simply won’t put anything out unless she feels on a gut level that it’s the best work she can produce at that given moment. As someone who found her 2001 post-O Brother album Time (The Revelator) as close to being a perfect piece of work as it is possible to produce, I have to admit I was a little disappointed by her 2003 follow up, Soul Journey. It wasn’t that I didn’t love it – there were some great individual songs on it, and I’ll listen with pleasure to anything Gillian sings in any case. But for me at least it had a bit of a commercial feel about it, and the tracks simply did not fit together the way the tracks on Time did. In its marvellous coherence, Time is like a set of linked short stories; Soul Journey felt more like a ‘best of.’

So I was apprehensive as well as excited when I heard that Gillian finally had a new album out. Could it possibly be as great as Time, or would it be another Soul Journey, enjoyable but not quite it?

I think if I tell you I’ve listened to The Harrow and The Harvest approximately twenty times in the last three days I think you’ll guess my answer to that question: Gillian Welch and her partner Dave Rawlings are at the top of their form, and this gorgeous album is worth every day of the nine-year wait.

How can I dsecribe her music, except to say that Gillian Welch is a natural born storyteller. The thing that’s most often said of her tracks is that they have the sense of being already old, of being handed down for generations among the musician-families of the Appalacians and the Adirondacks. I can’t add to that really because it’s true. The songs are like cross-stitch samplers, or patchwork quilts, the story as much in the making, in the texture of the warp and weft, as in the recounting of specific events.

Her language, both musical and verbal, is strong, simple, direct. The images she conveys are arresting and often stark. Yet there is a tenderness and poetry in the rendition that grabs at the heart.

The Harrow and The Harvest is not lighter than Time, but its silks are finer. If Time (The Revelator) reminds me of Wisconsin Death Trip, Harrow reminds me of Tarnation. The lyrics and rhythms of my favourite tracks – the central triptych of ‘The Way it Will Be,’ ‘The Way it Goes,’ and ‘Tennessee’ – already feel like they have been in my life for years.

Gillian Welch is a writer’s musician. Let’s just hope we don’t have to wait another decade for her next album.

Just started reading: Mr Fox, by Helen Oyeyemi. Loving it so far, magical and funny and assured.

Walking: along the Stade, with echoes of Daphne…..