In some ways this is my least favourite time of the year – I hate it when the clocks go back, and I am already looking forward to the spring equinox – and so anything that brightens it up is welcome indeed. Whether or not it’s appropriate to talk of Hallowe’en ‘brightening things up’ I’ll leave for you to decide – but as a moment to take stock, to light the fire (metaphorically if not literally) and make lists of favourite horror fiction and film then yes, for me it is!

Horror fiction comes in many forms, and the kind of horror I associate with Hallowe’en tends to have an elegiac, sepia-tinted quality that has as much to do with autumnal mists and shorter evenings as with the pagan festival of Samhain itself. Ironically, this would decidedly exclude offerings like John Carpenter’s 1978 slasher flick Halloween (not to mention its ludicrous sequels), which seems part of another genre entirely and as father of the jump-scare has done horror cinema no favours at all.

Here then are three unequivocal Hallowe’en recommendations, all of them British, all of them excellent. I hope you enjoy them.

1. The Inner Room by Robert Aickman.

‘Two rooms on the ground floor remained before I once more reached the front door. In the first of them a lady was writing with her back to the light and therefore to me. She frightened me also, because her grey hair was disordered and of uneven length, and descended in matted plaits, like snakes escaping from a basket, to the shoulders of her coarse grey dress. Of course, being a doll, she did not move, but the back of her head looked mad. Her presence prevented me from regarding at all closely the furnishings of the writing room.’

‘Two rooms on the ground floor remained before I once more reached the front door. In the first of them a lady was writing with her back to the light and therefore to me. She frightened me also, because her grey hair was disordered and of uneven length, and descended in matted plaits, like snakes escaping from a basket, to the shoulders of her coarse grey dress. Of course, being a doll, she did not move, but the back of her head looked mad. Her presence prevented me from regarding at all closely the furnishings of the writing room.’

One of Aickman’s longer works, this is a masterpiece among masterpieces, a horror story of uncommon power and disquieting political undercurrents, told in the restrained, deceptively quiet manner of the classic Victorian ghost story. It begins in an almost comedic manner: an observant, intelligent child describes what happens when her father’s car breaks down, leaving the family stranded for a couple of hours in an unfamiliar place. The result of this mini-adventure – the acquisition of a sinister dolls’ house the obtuse if well-meaning father insists on calling Wormwood Grange – has far-reaching consequences. Dolls’ houses are one of my obsessions anyway, and even re-reading the above short extract is enough to make me breathe a little faster. Any Aickman story would make ideal Hallowe’en reading, but with this one you get more pages to feast upon.

2. Don’t Look Now by Daphne Du Maurier

I happen to think Daphne Du Maurier is underrated. She’s world-famous, of course, with several of her novels adapted for film multiple times across multiple territories. She was a bestselling writer in her own lifetime, but what is not talked about so much – then or now – is what a good writer she is. As a highly successful woman, Du Maurier predictably found herself being type-cast as a writer of sensationalist suspense fiction, the kind of thing that was fine for entertaining the ladies but most definitely not to be taken seriously. Her novels make compulsive reading, yes – but they are also small masterpieces of narrative economy with a deftness of characterisation and style that reward repeated reading and warrant closer attention than they have often received*. Her short stories in particular are taut as drums. My first encounter with Du Maurier came through a dog-eared Penguin paperback of her collection The Blue Lenses. I was about thirteen at the time and I would say that my encounter with these stories formed a defining moment in my appreciation of horror fiction. I’m choosing Don’t Look Now as my Hallowe’en Du Maurier recommendation though because again, you get more story for your money, and because it exists with its 1973 film adaptation by Nicolas Roeg in a near-perfect equilibrium of mutual understanding. Could Roeg’s film be the greatest British horror film of all time? It’s certainly up there. Du Maurier’s original novella, a poignant and ultimately terrifying story of a married couple haunted by the accidental drowning of their young daughter, is not just a great horror story, it’s a sublime piece of English short fiction.

I happen to think Daphne Du Maurier is underrated. She’s world-famous, of course, with several of her novels adapted for film multiple times across multiple territories. She was a bestselling writer in her own lifetime, but what is not talked about so much – then or now – is what a good writer she is. As a highly successful woman, Du Maurier predictably found herself being type-cast as a writer of sensationalist suspense fiction, the kind of thing that was fine for entertaining the ladies but most definitely not to be taken seriously. Her novels make compulsive reading, yes – but they are also small masterpieces of narrative economy with a deftness of characterisation and style that reward repeated reading and warrant closer attention than they have often received*. Her short stories in particular are taut as drums. My first encounter with Du Maurier came through a dog-eared Penguin paperback of her collection The Blue Lenses. I was about thirteen at the time and I would say that my encounter with these stories formed a defining moment in my appreciation of horror fiction. I’m choosing Don’t Look Now as my Hallowe’en Du Maurier recommendation though because again, you get more story for your money, and because it exists with its 1973 film adaptation by Nicolas Roeg in a near-perfect equilibrium of mutual understanding. Could Roeg’s film be the greatest British horror film of all time? It’s certainly up there. Du Maurier’s original novella, a poignant and ultimately terrifying story of a married couple haunted by the accidental drowning of their young daughter, is not just a great horror story, it’s a sublime piece of English short fiction.

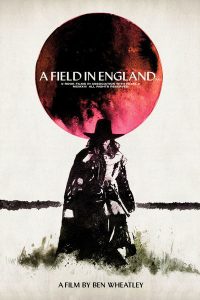

3. A Field in England dir Ben Wheatley screenplay Amy Jump

‘Quintessential’ is possibly the most over-used adjective ever among listmaniacs, but Ben Wheatley and Amy Jump’s 2013 film truly is the quintessential Hallowe’en watch. Set in the English Civil War, it tells the story of a bunch of common soldiers who flee the battlefield – in search of a pub, what else? – only to find themselves in mortal spiritual danger of the most uncommon kind. Shot entirely in black and white, A Field in England has in its jump-cuts and unscripted asides something of the quality of found-footage, but without any of the derivative and outworn tropes that have sadly become the defining features of that sub-genre**. This film is genuinely unnerving – some scenes made me go cold all over and that really doesn’t happen often when I’m watching horror films. It could be argued that Wheatley’s films kick-started the current renaissance in folk horror and A Field in England is, absolutely, the The Wicker Man of its generation. There’s only one problem with this movie: it’s almost too frightening to watch alone…

‘Quintessential’ is possibly the most over-used adjective ever among listmaniacs, but Ben Wheatley and Amy Jump’s 2013 film truly is the quintessential Hallowe’en watch. Set in the English Civil War, it tells the story of a bunch of common soldiers who flee the battlefield – in search of a pub, what else? – only to find themselves in mortal spiritual danger of the most uncommon kind. Shot entirely in black and white, A Field in England has in its jump-cuts and unscripted asides something of the quality of found-footage, but without any of the derivative and outworn tropes that have sadly become the defining features of that sub-genre**. This film is genuinely unnerving – some scenes made me go cold all over and that really doesn’t happen often when I’m watching horror films. It could be argued that Wheatley’s films kick-started the current renaissance in folk horror and A Field in England is, absolutely, the The Wicker Man of its generation. There’s only one problem with this movie: it’s almost too frightening to watch alone…

* Probably my biggest beef with Roger Michell’s really-quite-OK film adaptation of Du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel is that for some totally inexplicable reason he decided to replace the unforgettable first line of the novel – ‘They used to hang men at Four Turnings in the old days. Not any more, though.’ – with some bland paraphrase of his own. Madness.

** Stupidly, the only horror film I thought to bring with me to Paris was John Erick Dowdle’s 2014 As Above, So Below which is at least Paris-set, a fact that doesn’t, on balance, make up for its general ridiculousness. That being said, I do have a guilty affection for it. Must be the catacombs…