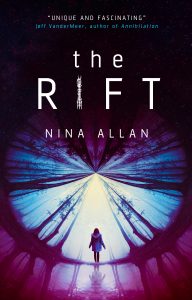

[Disclaimer: for the purposes of this essay, I am writing as if my own novel, The Rift, were not on the list.]

The 2018 Clarke Award submissions list is finally here! The number of books is slightly up on last year, with non-genre imprints – I’m delighted to see – making a particularly good showing. As always, there are any number of fascinating shortlists lurking amongst those 108 titles, with each combination highlighting a different and specific approach to genre. What such selections might theoretically reveal about individual critical standpoints – what constitutes science fiction and its current direction of travel – is what makes submissions list time so exciting and intriguing for me. While we must assume that the Clarke jury have already decided upon the six novels that will make up the official Clarke Award shortlist, for the Shadow Clarke jury, today is just the beginning. Even as I write this, they will be scanning the list intently, trying to decide which titles they hope will appear on the official shortlist, which they would most like to see discussed within the context of science fiction now.

I’m strictly an onlooker in the Sharke process this year – but of course that doesn’t stop me from wondering what I would pick! I’ve actually read more of the submitted titles in advance this time around, and there are even more on the list that I want to read. It’s interesting what hindsight will do. Looking at my choices from last year, it is clear to see that I made a conscious decision to go for a personal shortlist made up of titles from genre and mainstream literary imprints in equal proportions – in an attempt to curb my own biases, no doubt. If I had the choice again, and since having read the entire Sharke preference pool and then some, I would pick Don DeLillo’s Zero K, M. Suddain’s Hunters & Collectors, Joanna Kavenna’s A Field Guide to Reality, Martin MacInnes’s Infinite Ground, Catherynne Valente’s Radiance, and Aliya Whiteley’s The Arrival of Missives – all books that live in the memory in spite of any imperfections they may carry. My personal winner would still be Infinite Ground, a novel that even now is influencing my thinking, not just about science fiction but about the project and purpose of fiction in general.

In this revisionist state of mind, I’m going to play devil’s advocate this year and pick the shortlist I most want to see, a shortlist I know doesn’t stand a hope of actually happening – in fact I’d go so far as to say I’d be surprised if even one of these titles ended up on the official shortlist – but that best expresses my own current hopes and desires for science fiction literature. The reader might infer from this list that I have come to not give a damn about genre and they might well be correct, which is not to say that I don’t continue to believe that speculation in literature – whether that be in the matter of subject, form or language – is its most radical expression.

My personal preferred shortlist is as follows:

H(A)PPY by Nicola Barker. This choice won’t come as any surprise to anyone who reads my blog. I have long believed that Barker is one of Britain’s most interesting and important writers. For me, H(A)PPY was a magical and deeply unsettling reading experience, a book that will last and – most crucially – would deliver an even richer experience on rereading. As science fiction it is provocative and new, making use of established concepts to create a narrative whose originality lies not so much in its synopsis as in its execution.

Sealed by Naomi Booth. I’ve been hearing such great things about this and Booth’s novella, The Lost Art of Sinking, was excellent, beautifully written and tautly imagined. Going by the online preview, Sealed is even better, playing with themes similar to those that appear in Megan Hunter’s The End We Start From but with a harder edge. I liked the Hunter and it has stayed with me but I think I’m going to admire Sealed even more.

Memory and Straw by Angus Peter Campbell. ‘I know now that my ancestors had other means of moving through time and space, and the more I visit them the simpler it becomes. For who would not want to fly across the world on a wisp of straw, and make love to a fairy woman with hair as red as the sunset?’ I will be writing in greater detail about this book in due course. Angus Peter Campbell is a poet as well as a prose writer, as every page of this short novel about time, place and memory amply demonstrates. Campbell’s writing is pure imagination, made word.

Gnomon by Nick Harkaway. The big beast on this list in more ways than one! At more than 700 pages in length, Gnomon requires some commitment, but the reader will find that commitment amply rewarded. Freedom, information, truth – Harkaway paints big themes across a sprawling canvas in what is without doubt his most strongly achieved and important novel to date. The truly odd thing about Gnomon is how much in common it has with H(A)PPY in terms of its subject matter and what it chooses to do with it, though comparing the two might prove as difficult, if I may continue with the art analogy for just a moment, as comparing Vermeer’s The Lacemaker with Delacroix’s The Raft of the Medusa. My outright preferred Clarke winner this year would be either H(A)PPY or Gnomon, and I can see arguments for choosing either. To ignore them both would be a serious failure of nerve and imagination.

Euphoria by Heinz Helle. As far from Gnomon in terms of scope as it is possible to get, Helle’s novel focuses closely on a small group of friends at the dawn of an unexplained apocalypse. The language is terse, fractured, a shattered mirror to what is going on within the narrative. With a distinctly European accent on existential crisis, Euphoria was one of my favourite books of 2017 and one I will definitely be revisiting.

Black Wave by Michelle Tea. Billed as a ‘countercultural apocalypse’, this was on my list of books to read with the Clarke in mind in the immediate aftermath of last year’s award. I have only just got round to it, but I am loving it so far and it seems like exactly the kind of novel – existential, metafictional – the Clarke should be taking notice of, not to mention the Goldsmiths. The language alone – direct, abrasive, provocative – qualifies it for a place on my preferred shortlist in and of itself.

Very narrowly missing my cut are The White City by Roma Tearne – the writing is so wonderful that if I’d actually read the whole of this book at this stage then I might well have found it edging out one of the others – and Exit West by Mohsin Hamid, which is a vitally important text right now and a strong novel. Ask me tomorrow and you might find either or both of these on my list, and I’d be more than delighted to see the jury select them.

In my column for this month’s Interzone, I examined the reasons why science fiction might have found itself considerably better off had Hugo Gernsback never ‘invented’ the science fiction genre. Before Gernsback, speculative conceits floated freely in the mainstream of literature alongside every other kind of idea: political, social, metaphysical, confessional. Now more than ever, the ideas that for decades found themselves confined to the science fiction ghetto have been leaking out into the broader river of world literature, which – now more than ever – is where they belong. For proof of my thesis – that there is no such thing as ‘science fiction’, only books that make use of speculative ideas – look no further than the six (or indeed eight!) very different, challenging and original books above. If science fiction is truly to have a future, then this is it.