Apologies for my absence from the blog recently. The work-in-progress is currently in its final stages, and so the bulk of my concentration and energy is being poured into that. I hope to return to more regular posting soon. In the meantime, here is the transcript of a talk I gave yesterday evening to the North Bute Literary Society, which is not entirely unconnected with the novel I’m working on. This was fascinating to research and write, so much so that I have ideas about expanding it into something more substantial at a later date.

*

In a 2010 interview with the American publishing website GalleyCat, the British novelist David Peace talks about how he believes that crime writers, rather than inventing fictional serial killers, should concentrate their minds on interrogating the real events presented in newspaper headlines and police investigations. “I’m drawn to when writers take on history, take on real crimes,” he says. “To me there’s just so much that happens in real life that we don’t understand and we can’t even fathom. I don’t really see the point of making up crimes. I think that the crime genre is the perfect tool to understand why crimes take place, and thus tell us about the society we live in and the country we live in and who we are.”

Peace’s own writing has from the beginning centred itself upon real crimes. The Red Riding Quartet, set against the background of the Yorkshire Ripper murders of the late 70s and early 80s, takes its inspiration from the Yorkshire and specifically the Leeds of Peace’s own childhood and adolescence. His later Tokyo trilogy examines the political and social evolution of post-war Japan through the filter of three real-life crimes that shocked and polarised a nation already traumatised by war and the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki through the brutal force of Allied nuclear weaponry.

Peace claims as his most potent inspiration the American writer James Ellroy, who is so intent upon recapturing the atmosphere of the 1970s Los Angeles he writes about that he still uses a typewriter and has never owned a mobile phone.

We tend to think of the current interest in true crime as a modern phenomenon. Whether it be through podcasts like Serial, Netflix productions like Making a Murderer or closer to home, TV series like David Wilson’s Crime Files, which has a specifically Scottish focus, everyone seems to be talking about, watching or reading true crime. Along with popularity comes criticism – what is it about our society today that has led to what some call a prurient obsession with murder and murderers? Many, inevitably, have pointed to social media as the accelerant and you only have to look at the inappropriate and often abusive social media commentary around cases such as the recent, tragic death of Nicola Bulley in Lancashire to understand why.

Personally, I have always resisted the narrative around social media that has cast it as the chief villain of contemporary society. I happen to believe that social media is itself morally neutral, its agenda set entirely by those who use it. I would describe it not as the cause of a set of new and by extension worse behaviours but simply as a tool, a faster delivery system for the information, rumours, gossip, and scandal that has always obsessed us.

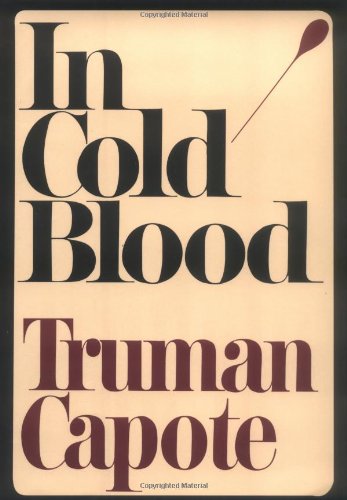

Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood was published in 1966 and is often hailed as the first ‘non-fiction novel’. In Cold Blood takes as its subject matter the murder, in 1959, of Herb, Bonnie, Nancy and Kenyon Clutter, a Kansas farming family by small-time criminals Richard Hickock and Perry Smith. The two had recently been released from prison after serving time for robbery. They arrived at the Clutter house expecting to make away with more than $10,000. What they got was $40. Capote took more than 8,000 pages of notes in the course of writing the book, which brings the events to life using the techniques of New Journalism – a personal agenda, imaginative reconstruction and the interleaving of multiple points of view. As the writer Rupert Thomson puts it:

“Capote saw journalism as a horizontal form, skimming over the surface of things, topical but ultimately throwaway, while fiction could move horizontally and vertically at the same time, the narrative momentum constantly enhanced and enriched by an incisive, in-depth plumbing of context and character. In treating a real-life situation as a novelist might, Capote aimed to combine the best of both literary worlds to devastating effect.”

Just two years later, the playwright Emlyn Williams turned a similar focus upon the Moors Murderers Ian Brady and Myra Hindley in Beyond Belief, a work that similarly blends hard facts with imaginative reconstruction and that lays emphasis not on the crimes so much as the social background and family circumstances that made Hindley and Brady such an appalling influence on one another.

Both these books were instant bestsellers – and instantly show us that the interest in true crime, for both reader and writer, long predates the advent of the internet. And we can trace that interest back far further than Capote. As early as 1875, the writer Wilkie Collins, perhaps most famous for his fictional mystery The Woman in White, wrote The Law and the Lady, a novel freely inspired by the trial of Madeleine Smith in 1857, a case that also inspired William Darling Lyell’s 1921 novel The House in Queen Anne’s Square. In 1912, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, best known as the creator of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, wrote a freewheeling true-crime account of another Glasgow case, the gross miscarriage of justice against Oscar Slater, falsely accused of murder and whose case was famously taken up by Doyle himself.

In my previous talk for this society, we concentrated upon writers associated with the so-called Golden Age of detective fiction, the period between the wars when the social order was rapidly changing and whose excitement and unease were so inventively tapped by detective writers. We tend to think of the Golden Age writers as spinning convoluted, sometimes fanciful ‘puzzle plots’ – the antithesis of the gutter-level vantage point of true crime narratives. As it turns out, the Golden Age writers were as fascinated and inspired by real-life crimes as any of their grittier modern counterparts.

The Anatomy of Murder, published in 1936, is a collection of essays by Golden Age writers such as Dorothy L. Sayers, Francis Iles and Helen Simpson examining some of the most famous true-crime cases of the era. In his introduction to a recent reissue of the book, crime writer, historian and latter-day president of the Detection Club Martin Edwards talks about the fascination felt by Golden Age writers for real cases, how Detection Club meetings would often feature engaged discussion on the latest theory or new piece of evidence. Nor did they confine themselves to abstract discussions. Novels directly inspired by true crimes were as common and popular then as they are now, with many of them displaying much of the same concern and fascination with the social background to crime and the inequalities within society that is often influential not only upon the causes of crime, but how crime is seen and judged.

Perhaps the most written-about criminal ever is Jack the Ripper, whose true identity, ironically, remains unknown unto the present day. Anyone who suspects that behaviours such as trolling and the spreading of ‘alternative facts’ are the product of the internet age might do well to take a look at some of the spurious letters, communications and false rumours that deluged down upon the heads of officers charged with investigating these brutal murders in the Whitechapel of 1888.

More than a hundred years later, crime writers, podcasters and film makers are still writing and talking about the unidentified serial killer. One of the very first novels to take the Whitechapel murders as their key inspiration is The Lodger, written in 1913 by Marie Belloc Lowndes, the sister of the poet and satirist Hilaire Belloc. Sometime in 1910, Marie Belloc Lowndes attended a dinner party where she heard from the painter Walter Sickert of how the landlady of his then apartment in Mornington Crescent first showed him the rooms, telling him that she was sure a previous tenant had been Jack the Ripper. Sickert famously painted the room as ‘Jack the Ripper’s bedroom,’ drenching the scene in his characteristic umber light, producing an ambience of dingy notoriety. Belloc Lowndes drew just as much inspiration from the tale, which inspired a short story published in McClure’s Magazine in 1911, a story that proved so popular with the readership that Lowndes decided to expand it into a novel.

The Lodger tells the story of Bunting and his wife Ellen, who keep a lodging house on the Marylebone Road. The Buntings meet while they are both in service, Bunting as a manservant and butler and Ellen as a maid. They work in good houses for generous employers, eventually acquiring enough money to set themselves up on their own. However, a series of disappointments and unforeseen accidents have left them without an income and as Lowndes’s novel opens they are desperate. Lowndes makes a point that might well have been missed by modern readers otherwise, that had the Buntings been either poorer to begin with, or more middle class they would have been more certain of finding help within their community. As things stand, they belong to no class, and so are thrown back on their increasingly depleted resources.

When a mysterious stranger presents himself looking for lodgings, Ellen feels his presence almost as a divine intervention. Mr Sleuth, she is certain, is ‘a proper gentleman’. A touch eccentric yes, but quiet, decent and god-fearing, a teetotaller like herself. His needs are simple, and if his habits seem strange then the money he offers in return for his rooms is ample compensation. For the first time in many months, the Buntings see the possibility of a new start. But when a series of gruesome murders becomes the talk of the neighbourhood, Ellen Bunting begins to notice an uneasy correspondence between the scenes of the crimes and her lodger’s nocturnal rambles. As the body count rises, Ellen’s imaginings take on the quality of nightmare.

The Lodger is a fascinating social document, evoking a world in which class is still absolutely the most defining factor in society. In spite of mounting evidence to the contrary, the police find themselves unwilling, almost unable to believe that crimes of such a violent and sordid nature might be the work of a ‘gentleman’, and Lowndes is astute in demonstrating how their blinkered approach actively hampers their investigation. Lowndes’s portrait of Ellen Bunting is the most nuanced, revealing her increasing fascination with the crimes and the ways in which her insights lead her into places and behaviours that would previously have been unthinkable. A romantic subplot involving Bunting’s daughter from a previous marriage dovetails neatly with the main action when Daisy finds herself falling for a detective constable involved with the murder investigations. The Lodger is plainly written, unostentatious in terms of its literary style but Lowndes is an honest craftswoman with a nose for a good story and her descriptions of a London caught up in murder fever are given extra life by her knowing references to other real-life crimes of the period and her professional insights into tabloid journalism and the public thirst for sensation and especially for true crime. Bunting’s clandestine pursuit of his murder fixation in the Evening Standard will raise a knowing smile from all modern day podcast junkies:

Thanks to that penny he had just spent so recklessly he would pass a happy hour, taken, for once, out of his anxious, despondent, miserable self. It irritated him shrewdly to know that these moments of respite from carking care would not be shared with his poor wife, with careworn, troubled Ellen.

Anyone reading The Lodger when it was first published would have been acutely aware of its realworld resonances, and accordingly thrilled.

Lowndes was a prolific writer and journalist, active in society and constantly on the lookout for material suitable for adaptation into the hugely popular novels that, essentially, supported her family. The writer of our next book, Elizabeth Jenkins, was of a very different temperament. Shy and something of an introvert, she was an intensely private woman, who chose her subjects carefully and who expressed her opinions obliquely within her writing. Margaret Elizabeth Jenkins was born in 1905, and lived into our current century, dying at the age of 104. Jenkins studied English and History at Newnham College, Cambridge, and worked variously as a teacher and civil servant before becoming a full-time writer after WW2.

Her most popularly successful novel, Harriet, was published in 1934 and was awarded the Prix Femina, beating both Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust and Antonia White’s Frost in May. Harriet is based on the infamous Penge murder trial of 1877, fully ten years before the Ripper crimes but a case that excited at least as much attention at the time.

Jenkins, who often insisted she needed the firm armature of a real-life incident to inspire her best writing, first learned about the case when her brother David, who was a solicitor, gave her a copy of The Trial of the Stauntons by JB Atlay, one of the volumes in the Notable British Trials series. David thought the peculiarly enmeshed, secretive family relations at the heart of the case might be of interest to Elizabeth, and he wasn’t wrong. She quickly found herself becoming obsessed with the Stauntons – or the ‘Cudham quartet’ as they became known – and decided to write a novel about them. This of course was Harriet, which in Jenkins’s own words was to be “one of the very earliest instances – if not the earliest – of a writer’s recounting a story of real life, with the actual Christian names of the protagonists and all the available biographical details, but with the imaginative insight and heightened colour which the novelist exists to supply’.

Harriet Woodhouse – Harriet Richardson in real life – lives in London with her mother and stepfather, her birth father, a well-to-do clergyman, having died when Harriet was twelve. As well as a generous settlement from her father’s will, Harriet has been left a sizeable sum of money by an aunt. Harriet has learning difficulties, and although she has a lively and curious nature she depends heavily upon her mother, who has always been determined that her daughter should gain as much life experience as possible within a safe environment.

Harriet is in her early thirties when she first comes into contact with the significantly younger Lewis Oman at the house of a near relation. Lewis, an auctioneer’s clerk, is a good looking young man, and when he starts paying special attention to Harriet she quickly becomes infatuated with him. When he proposes marriage, Harriet’s mother realises immediately that he has no real affection for her daughter, but very real designs on her money. She attempts to have Harriet certified as a lunatic in order to prevent the marriage and protect her daughter, but the family doctor is quick to warn her that this plan will probably fail:

‘You must see,’ said the doctor, ‘that what she’s doing now is done by hundreds of young women who to all intents and purposes are as sane as we are: alarming her friends by wanting to throw herself away on a worthless young man.’

The horror of Harriet’s eventual fate is equalled only by the bizarre network of relationships and lies that enable it. Elizabeth Jenkins’s abiding interest as a writer is centred upon human relationships – between men and women, between families – and her understanding of the characters at the heart of this story is acute and brilliantly rendered. She enters into the mind and heart of each person equally, whether they be innocent, guilty, or a little of both. Her descriptive writing has immense power, as we see here in her description of Lewis, standing at the London dockside not long before his devious plan goes into operation:

Hoarse cries sounding from the water, unintelligible words ceaselessly filling the ear, the perpetual hurrying to and fro of figures in the gloom, made an atmosphere so enthralling that hours passed unnoticed; and as Lewis stood amidst this stir he knew that a power was coming to him, too, that he was about to enter the sphere of those who moved the world by their activity; that whole tracts of his own being were waking to life which had lain stagnant in the routine of poverty and restricted labour.

Four people stood trial for Harriet’s murder: Lewis himself, his brother Patrick, Patrick’s wife Elizabeth and Lewis’s lover Alice. They were sentenced to hang, a judgement that was commuted to a pardon for Alice, and life imprisonment for the others just forty-eight hours before the executions were due to be carried out. Patrick died in prison just a couple of years later. Elizabeth and Lewis were released twenty years later in 1897. Lewis finally married Alice and the couple emigrated to Australia. Elizabeth went on to run a boarding house, where the rumours surrounding her never entirely subsided.

Elizabeth Jenkins did venture into true crime again with her 1972 novel Dr Gully, based on the affair of Dr James Manby Gully, his affair with Florence Bravo and the consequent suspicious death of her husband Charles. Jenkins claimed Dr Gully, published in 1972, as her favourite among her own works.

The third of our spotlighted books was published in the same year as Harriet, though the case that inspired it has remained much closer to the centre of public consciousness, quite possibly because, for one of those who stood trial at least, the eventual outcome represents one of Britain’s most horrific miscarriages of justice, one that even at the time led to vociferous calls for the abolition of the death penalty. The case of Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters, popularly known as the Ilford murder, took place in 1922. Edith, unhappily married to the rather staid and predictable Percy Thompson, became passionately attached to Bywaters, a young and handsome merchant seaman who was originally a friend of both the couple, so much so that Percy Thompson offered him lodgings in their house in Ilford.

When Bywaters stabbed Percy Thompson to death in the street in October 1922, he claimed he never set out to kill him, wanting only to confront Thompson in an attempt to resolve the situation between the three of them. Edith played no part in the murder and had no idea Freddy was even in the vicinity. She was arrested solely on account of the love letters she wrote to Bywaters, found in his room after his arrest and filled with tirades against Percy and fantasies about possible ways to get rid of him. The two were jointly convicted according to the ‘rule of common purpose’, and in spite of a million-strong petition pleading for mercy, they were hanged at the beginning of January 1923.

Edith’s case has generated a substantial amount of both fiction and non-fiction over the years and the horror of her execution – the hangman in question, John Ellis, later took his own life – has continued to generate discussion as a standing argument against the death penalty. One of the most interesting fictional treatments of the case is Fryn Tennyson Jesse’s 1934 novel A Pin to See the Peepshow, which is as much an exploration of the background and particular character of Thompson herself as an account of the crime and of the trial. Jesse, a writer and journalist who was the great-niece of the poet Albert Lord Tennyson, had a longstanding interest in criminology and the law. She edited and introduced several volumes in the Notable British Trials series, most notably the Madeleine Smith case and the John Christie case. In 1924, she published the investigative volume Murder and its Motives, positing the theory that there are six main categories of motive that might lead to murder: Gain, Revenge, Elimination, Jealousy, Conviction and Lust of Killing.

In contrast with the rigorous, fact-based approach taken by Elizabeth Jenkins in Harriet, Jesse tells her story using characters and situations more loosely inspired by the real people involved. A Pin to See the Peepshow focuses on the young Julia Almond, an intelligent, articulate and highly imaginative young woman from a lower middle class family who makes a dull marriage and soon wishes herself out of it. From the very beginning, we observe Julia’s love of romance, her desire for excitement and for a life beyond the ordinary suburbs of her upbringing. Her tendency to daydream, to fantasise is beautifully captured by Jesse, not least in the passage that gives the novel its name. Here we see the sixteen-year-old Julia, who is minding a class of younger pupils while their teacher is absent, confiscating a home-made ‘peepshow’ box from the nine-year-old boy who, a mere ten years later, is to change her life forever:

Then she picked up the box. A round hole was cut into each end, one covered with red transparent paper, one empty. To the empty hole was applied an eye, shutting the other in obedience to eager instructions. And at once sixteen year old, worldly wise London Julia ceased to be, and a child, an enchanted child was looking into fairyland. The floor of the box was covered with cotton-wool, and a frosting of sugar sprinkled over it. Light came into the box from the red-covered window at the far end, so that a rosy glow as of sunset lay over the sparkling snow. Here and there little brightly-coloured men and women, children and animals of cardboard, conversed or walked about. A cottage, flanked by a couple of fir trees, cut from an advertisement of some pine-derivative cough cure, which Julia saw every day in the newspaper, gave an extraordinary impression of reality and of distance. This little rose-tinted snow scene was at once amazingly real and utterly unearthly. Everything was just the wrong size – a child was larger than a grown man, a duck was larger than a horse; a bird, hanging from the sky on a thread, loomed like a cloud. It was a mad world, compact but of insane proportions, lit by a strange glamour. The walls and lid of the box gave to it the sense of distance that a frame gives to a picture, sending it backwards into another space. Julia stared into the peepshow, and it was as though she gazed into the depths of a complete and self-contained world, where she would go clad in snow-shoes and furs, and be able to tame savage huskies and shoot bears; a world of chill pallor, of an illimitable white sky, both only saved from a cruel rigour by the rosy all-pervading light.

To end with this passage seems particularly appropriate, because Jesse demonstrates so well in her writing how fiction has an important part to play not just in bringing information about true-life crimes to public awareness, but in digging deeper into the personal psychology, historical background and possible motivations that might have had an impact on the case. The glorious thing about fiction is that it sets you free to imagine beyond what is already known.

As a final postscript, Edith Thompson’s heir and executor, Rene Weis, who has long petitioned for an official pardon for Edith, finally had his application referred to the Criminal Cases Review Commission in March of this year. I hope that it succeeds. Nothing can make amends for the horror of her execution, but I like to think at least that Edith – imaginative, romantic, adventurous Edith – would be pleased to know that a century after her death, she is a poster girl for women’s justice as well as a figure of inspiration for writers and film makers. Edith Thompson was unjustly killed, dying well before her time, but she has ended up becoming immortal and of that we can be glad.