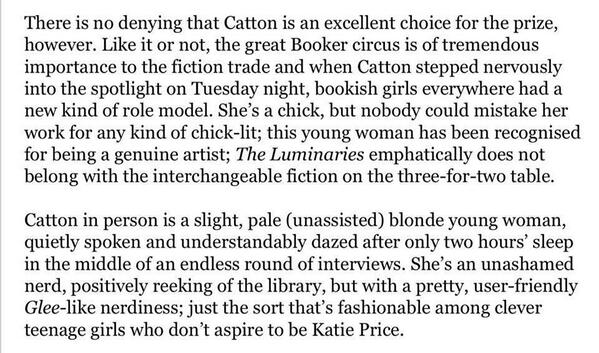

I read a blog post by Adam Roberts over the weekend, in which he talked interestingly about the cultural significance of so-called Young Adult fiction and the challenge it presents to literary prizes like the Booker, which, as Adam would have it, ‘likes complex, challenging art’ but that which ‘never, ever rewards primitivist art.’

Adam wrote his post in response to an article on the OUP blog by a colleague of his at Royal Holloway, Robert Eaglestone, and a follow-up discussion on Twitter about the Booker shortlist. Eaglestone argues that said shortlist is diverse and innovative, Adam counters that in ignoring SF, crime, and YA, the Booker is deliberately avoiding engagement with three of the most culturally significant literary trends of the present time, thereby rendering itself irrelevant and parochial.

Familiar arguments then, and I’d say I’ve found myself on Adam’s side in those arguments far more frequently than not. I admire Adam’s literary criticism hugely – it combines erudition with a sharpness of wit that do not always make a natural pairing. His commentary on last year’s Booker was a tour de force and a joy to read. Why then, apart from the fact that I normally respect Adam so much as a critic, did I find myself becoming more and more uncomfortable with his post on YA? Why did I spend a significant amount of time over the weekend thinking about it, and coming finally to the decision that I had to reply?

Well, mostly because of this:

Imagine a music prize that has, through the 70s and 80s and up to the present, shortlisted only abstruse jazz, contemporary classical and Gentle-Giant-style prog rock concept albums. I love my prog rock, and partly I do so because it ticks all those aesthetic boxes I mention above—it is complex and challenging and intricate music. But I wouldn’t want to suggest that prog has had anything like the cultural impact or importance as pop, punk or rap. That would be silly. So how would you tell the judges picking those shortlists about the Ramones, the Pistols and the Clash? How would you persuade them that they’re missing out not just good music but actually the music that really matters?

Which is all well and good – once again, I agree with Adam. The problem is that the analogy he is presenting seems utterly false, because the literary equivalents of The Ramones, The Sex Pistols and The Clash (and Kristin Hersh and Siouxie and Patti Smith) are not Suzanne Collins, J. K Rowling and Stephenie Meyer, as Adam would have them here, but Charles Bukowski, James Kelman, Irvine Welsh, Sarah Kane, Janice Galloway and (much though he pisses me off a lot of the time) Bret Easton Ellis. In terms of sophistication, formal achievement, and the way their product is received by its intended audience, Meyer et al are actually closer to the manufactured boy- and girl-bands that (like Meyer, Rowling and Collins) started coming to prominence in the nineties and noughties. Both are a cultural phenomenon, yes – but in terms of what one might call the Ongoing Literary Project (and the Booker Prize is expressly about the Ongoing Literary Project) their status is negligible. Complaining that Booker will never reward the ‘artistic primitivism’ of Breaking Dawn is like complaining that the jury will never award the prize to Fifty Shades of Grey.

There is another crucial point here that Adam never addresses. The punk and alternative bands of the 1970s (and continuing into the present day) were and are themselves made up of (necessarily slightly older) young adults, making music for themselves, for their peers, in the way that best expresses their view of the world and their fears for its future. Commercial YA fiction is (in the vast majority of cases) written by adults, for consumption by readers younger than they are, or to call it by its proper name, for the young adult market. Moreover, the market certainly and in many cases the books Adam names in his blog post are not progressive, as he suggests, but didactic. The Twilight series certainly is, and both his books and his many interviews make it impossible to forget that Philip Pullman was a teacher before he ever became a full time writer.

Mass market YA is not representative of some kind of social revolution, nor is it even properly zeitgeisty. Adam talks about the Harry Potter novels as ‘one of the great representations of school in Western culture,’ yet how many kids in Britain today could realistically compare their own schooldays with Harry’s time at Hogwarts, and I’m not just talking about the magic? Adam lauds the way sex is characterised in the Twilight books as ‘something simultaneously compelling and alarming, that draws you on and scares you away in equal measure’ – well, if that’s how you want to describe the bizarre and (to me) seriously dodgy amalgam of titillation and partisan prudery that is the strongest characteristic of these narratives, then OK. If you don’t, then you’ll be bound to admit that most of the most popular YA series are – like the manufactured pop that dates even as you download it – anodyne and half baked even in cultural terms, let alone in literary terms.

Let me make myself clear: it is not YA as such that I’m objecting to (much though I personally dislike the rather pointless label that has been slapped on it) but Adam’s (devil’s advocate? can he really be serious?) insistence on the lowest common denominator, on his confusion here of the popular with the excellent or culturally significant. There is absolutely nothing wrong with young adults reading, enjoying, discussing, role playing or writing fan fiction about Harry Potter or Twilight. There’s no doubt that the power of story that exists in these books is considerable, and marvellous, and that the authors can and should be congratulated and rewarded for helping to instil in younger people an enjoyment of reading and perhaps also of writing that will often continue into adulthood. There’s nothing inherently wrong with adults reading and enjoying this kind of popular YA either, so long as they acknowledge it for what it is, which is literary comfort food. But what Adam seems to be doing in his article is the equivalent of demanding that Star Trek novelisations should be placed on a level playing field, in literary prize terms, with seriously intended and formally accomplished works of speculative fiction such as those produced by M. John Harrison or Liz Jensen or Simon Ings or even Adam himself. Bollocks, is what I say to that. If we want YA to be taken seriously, shouldn’t we be pointing readers – and critics, and the judges of literary prizes – away from the sludge at the bottom of the literary barrel and towards those books and writers that genuinely do represent excellence, and cultural significance, and literary innovation in their writing for young adults? I’m sure that’s what Adam would do if he were arguing a similar case for SF, so why not here? Because (as with SF, as with crime) there are a wealth of books that fit into the young adult bracket that are also worth reading as literature. Natasha Carthew’s Winter Damage, Sally Gardner’s Maggot Moon, Helen Grant’s The Glass Demon and Rachel Hartman’s Serafina to name but four recent examples, the fiction of Melvyn Burgess and Frank Cottrell Boyce and Frances Hardinge and wonderful Margo Lanagan. As with science fiction itself, the list is extensive.

Nor is it correct to assume that YA will ‘never’ be rewarded or even acknowledged by the likes of the Booker. YA is already making its way on to the shortlists of the major ‘adult’ speculative fiction prizes – see Patrick Ness’s Monsters of Men in 2011, Rachel Hartman’s Serafina earlier this year. Jenni Fagan’s YA-friendly The Panopticon, also a finalist for this year’s Kitschies, has been widely praised in the literary mainstream and Fagan was herself named as one of 2013’s Granta Best of Young British Novelists. There was plenty of discussion, both before and after it won the Clarke Award in 2012, as to whether Jane Rogers’s The Testament of Jessie Lamb should be classified as YA – and yes, there it was on the Booker longlist. These books have been recognised by prize juries because they are good books – that is, demonstrating significant accomplishment in terms of style, use of language and literary form. Whether they are YA or not (or SF or not, or crime or not) is of secondary importance.

Adam complains that the Booker never rewards ‘primitive’ art. I’m not sure if he’s wanting to categorise the whole of SF as primitive art along with mass market YA – I know I wouldn’t (just read Light) – but the central question here is: do we want it to? What could possibly be gained by a panel of Booker Prize judges deciding to give the nod to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows? This surely is not what the Booker – or the Clarke, come to that – is for. The way mass consumables work in the marketplace should never be confused with what literature does, which is to be sceptical, to question, to call to arms, to stretch the imagination and the intellect, to further the possibilities of what printed words on a piece of paper can accomplish. One could argue, perhaps rightly, that reaching a lot of people is in and of itself a significant literary achievement. But The Daily Mail reaches a lot of people and I don’t see Adam arguing that the Mail – that most perniciously conservative of daily rags – should be held up as an icon of the zeitgeist.

The task of literature – and that includes our YA literature – is not to reflect mass trends, but to buck them. The task of the Booker Prize, surely – and of the Clarke, and the Kitschies – is to recognise writers who are genuinely striving to do that.