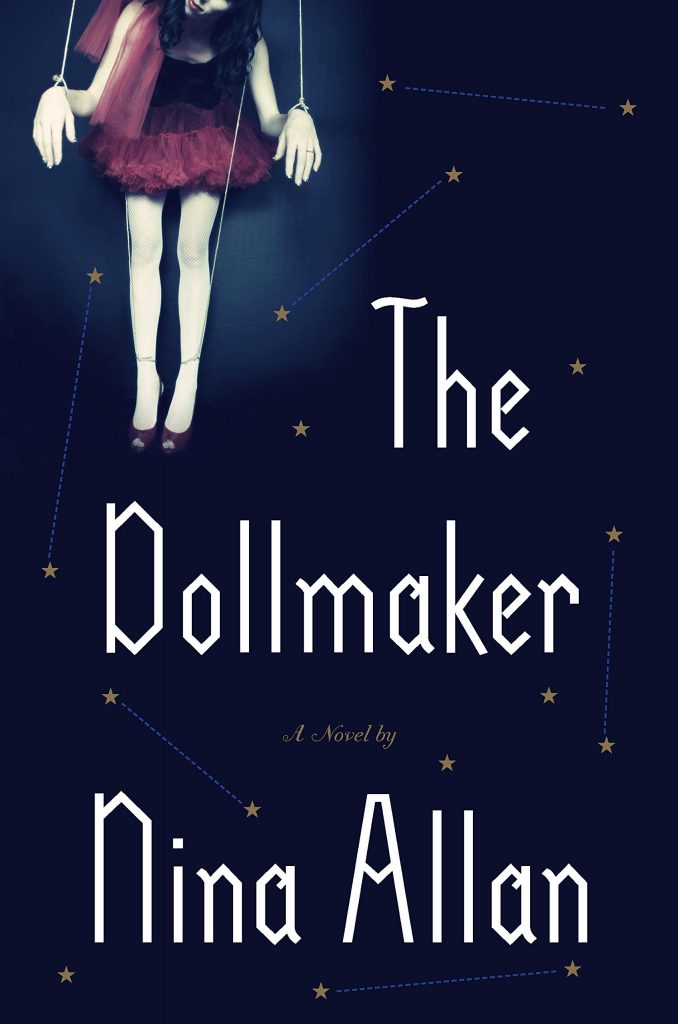

The Dollmaker is published in the US today – excuse me while I gloat over the fantastic (and creepy) cover art:

Huge thanks to Judith Gurewich and the whole incredible team at Other Press for steering Andrew on his journey across the Atlantic.

Nina Allan's Homepage

The Dollmaker is published in the US today – excuse me while I gloat over the fantastic (and creepy) cover art:

Huge thanks to Judith Gurewich and the whole incredible team at Other Press for steering Andrew on his journey across the Atlantic.

I read The Handmaid’s Tale not long after it was published. I was still at university and I remember it was a much talked-about title, even then, in the way that William Styron’s novel Sophie’s Choice had been when the film adaptation came out, which happened to be the year I started doing my ‘A’ Levels. I tend to think of these two novels, still, as a kind of pair – both discussed important ideas, both had a profound effect on me at the time, both – again, at the time – felt safely removed from my lived reality. For my young-adult self, these novels provided a significant focus for my developing intellect, an illustration of how bad things might – could – get if complacency were allowed the ascendancy over political engagement.

I remember reading The Handmaid’s Tale and feeling a visceral, red-robed hatred of Gilead’s organising structures and founding ideology. I also remember reassuring myself that as a society we had moved past these dangers, that the arguments Atwood was rehearsing were largely theoretical.

I was a child of the Cold War. The year The Handmaid’s Tale won the Clarke Award, I was in Russia meeting other young students and experiencing first hand the stirrings of a new political reality that would bring down the Berlin Wall only two years later.

Yes, it was incredible and yes, it feels like ancient history. The Handmaid’s Tale became an instant classic because it is so perfectly conceived, so exquisitely judged as writing, so powerful as story. But the definition of a classic goes further: for a book to remain in the literature it must continue to feel relevant, ten, twenty, fifty, one hundred years and more after it was written. A relatively short thirty years after Atwood wrote her breakout book, it feels more relevant, more important and certainly more terrifying than it did when it won the Clarke Award. In political terms this speaks for itself. In literary terms it is an incredible achievement, and a marker of Atwood’s status as one of the most important writers of the post-Vietnam period.

I was not able to be at the London event to commemorate the launch of her sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, The Testaments, but I was lucky enough to bag a ticket for the live cinema broadcast of that event, an interview with Samira Ahmed interspersed by readings from the new novel by actors including Ann Dowd, who plays Aunt Lydia in the TV adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood has grown gracefully into her role as literary grande dame and she is wonderful in interview: incisive, insightful, sardonic, quick-witted, fearless, funny. I feel lucky to have been there, as it were, and nothing could diminish my admiration for Atwood both as a writer and as a human being. But what of The Testaments itself? It is a book that seemed desperately wanted, but did we need it? And, to put the question bluntly, is it any good?

The answer to both questions, as so often, is yes and no. There is so much commentary on The Testaments available online now that to summarise the plot again here seems superfluous to requirements. Suffice it to say that the novel comprises three alternating first-person narratives, that the architecture of the novel is structured around revealing the links between them. One of the narrators we know already – or at least we think we do. The other two we have previously glimpsed – but at some distance. The thrust of the novel’s action concerns the fate of Gilead as a political system. Where The Handmaid’s Tale was slow, interior, close-focus, its acute tension derived from the withholding of knowledge and answers, The Testaments is structured more like the later, non-book-related TV series of The Handmaid’s Tale: information is withheld, but only until the next episode. Characters are there not simply as their complicated, contradictory selves, but to represent particular facets of a problem or system. There is action and there is cruelty. There is plot exposition in the form of dialogue.

It reads well because it is Atwood and she has now reached that summit of experience where she can – in all likelihood literally – write in her sleep. But the whole enterprise feels lightweight to me, a MCU version of The Handmaid’s Tale in which cruelties are avenged and villains are vanquished. Most superhero movies bore me because they’re morally simplistic (even the ones that strain so desperately not to be). The Testaments feels the same. I came across a reader review the other day that said The Testaments felt like YA, ‘as if the sequel to Nineteen Eighty-Four turned out to be The Hunger Games’. I can’t think of a more accurate critical summation.

In answer to my original questions, I would say personally that no, we did not need this book. In terms of language, interiority, structure, conceit, complexity and resonance it lacks the power of the original. If The Testaments were by a lesser known author and did not have the might and weight of The Handmaid’s Tale to act as an anchor, it would quickly become lost among all the other similarly timely feminist dystopias currently being written and consumed. At the level of reading pleasure, it has plenty to offer. I turned its pages quickly and with enjoyment, finding the first half (the set up) a great deal more interesting than the facile-seeming denouement, but then that’s true for me of virtually all mass-market SFFH. I did not hate it – not at all. I will remember it with affection because of everything it represents about Atwood and about now. But taken purely for itself, as text, it is disposable.

Even in spite of this, there is a case to be argued that rigorous critical appraisal of The Testaments is not the point of the story, that this is not a book so much as a phenomenon. I find it interesting and moving that the generation of young women who are growing up with the TV version of The Handmaid’s Tale, many of whom will have read the novel after seeing the series, are precisely those who have flocked in such numbers to launch events for The Testaments, who have queued outside bookstores at midnight to obtain their copies first, who have felt such a passionate sense of ownership of the original novel and its characters that it is they, in some sense, who would seem to have provoked and inspired Atwood into writing a sequel, where thirty years of steady sales and campus admiration did not. In a very real sense The Testaments is their book, not mine. That the book exists is in itself a phenomenon, a testament to the power of The Handmaid’s Tale and its own justification.

Does The Testaments diminish the power of the original text? Of course it doesn’t, and nor should it. But whilst I will hope to continue visiting with The Handmaid’s Tale, The Blind Assassin, Alias Grace, my beloved Cat’s Eye, Oryx and Crake even, and those marvellous interlinked stories in The Stone Mattress, I cannot imagine wanting or needing to reread The Testaments, which if not a bad book is a weak book by comparison. Its solutions are too easy, too rapid. It feels like wish fulfilment. No doubt I’ll watch the TV adaptation, when it inevitably arrives on our screens, but I already know in advance that it will vaguely annoy me.

I’m thrilled to announce that La Fracture – the French-language edition of The Rift – has this past week been longlisted for two of France’s most prestigious and enduring literary prizes: the Prix Medicis, established in 1958 to recognise authors ‘whose fame does not yet match their talent’ and the Prix Femina, established in 1904 and decided each year by an exclusively female jury.

Glancing down the list of past recipients, I feel quite overwhelmed! This year’s longlists can be found here, and here. Finding myself in such company is surreal, to say the least.

I am incredibly pleased for my French publishers, Editions Tristram, who have been staunch and stalwart in their commitment to my work right from the beginning, and doubly indebted to my translator, Bernard Sigaud, without whom none of this would be happening.

They’re all amazing people and these longlist placings belong equally to them. Salute!

A couple of weeks ago I was fortunate enough to catch the writer Rebecca Stott reading her essay ‘On Ghost Cities’ on Radio 4. Drawing on her early childhood, when her family were still part of the Exclusive Brethren, Stott describes her enduring fascination with urban spaces forsaken by their human inhabitants, either through gradual depletion or traumatic change. For Stott, the imagery of cataclysm was not alien, but something she had lived with as a daily reality. I found Stott’s essay beautiful and profound, full of ideas that resonated with me on a personal level. It also served to remind me that I had not yet read In the Days of Rain, Stott’s Costa-winning memoir of her family’s connection with and eventual severance from the Exclusive Brethren. Which is how I came to be reading it on the train this Tuesday as I travelled into Glasgow to attend a live screening of Margaret Atwood’s launch event for The Testaments at the NFT.

In truth, Ada-Louise’s face had come to stand for all those women who’d been shut up or locked up. Not just Brethren women, but all women who’d been bullied or belted by men who’d been allowed too much power in their homes. Her face haunted me. One day when my daughters were a bit older, I told myself, I’d talk to them about that, about patriarchy and how dangerous unchecked male power can be. I’d talk to them about Ada-Louise.

“Mum, you’ve read The Handmaid’s Tale,” Kez said. “You know we can’t ever take feminist progress for granted. They’ll take our freedom away again unless we protect it.”

One of those strange coincidences that feel like more than coincidence, when a particular text falls into your hands precisely at the time you need to be reading it. In the Days of Rain is more than just a memoir. Written when Stott was already mid-career and fully in command of her material, it is a furious and tender examination of faith, credulity, community, scepticism, love, folly and the human propensity for both the numinous and the monstrous. It is also a book about women and the numberless ways in which – then and now – they are set up to act as scapegoats for men’s greedy descent into violence and error.

There’s more, though. While Stott wholeheartedly condemns the psychological and latterly physical and sexual abuse that came to define and ravage the Exclusive Brethren, she remains determined to explore the more surprising truths of what it is like to have one’s formative experiences and imagination shaped by living in what is, in effect, a parallel universe.

What is clearly difficult and sometimes painful for Stott to explain is that not all of these experiences are negative. I found these parts of the book – Stott’s examination of the language, imagery and philosophy of visionary belief – affecting and thought-provoking. As I happen to be in the early stages of work on a novel that deals with some of the same themes I cannot help thinking and wondering about the recent crop of writers – all of them women – who have drawn vital inspiration from their experiences of life in faith communities: Tara Westover, Sarah Perry, Grace McCleen, Miriam Toews. Their work is luminous. The questions they ask are hard questions. Most remain unanswered.- .

Atwood’s interview with Samira Ahmed – witty, mischievous, deeply intelligent and fiercely timely – set a new standard in book events. It was a privilege to be present at its screening, heartening to learn afterwards that the multi-venue livestream topped the UK’s cinema box office takings for that day. Having Rebecca Stott as my literary companion in the hours before and afterwards provided a powerful poetic symmetry. I am still thinking about her book and what I can learn from it. I am still thinking about ghost cities, the many uncanny ways in which the future continues to leak into the present.

Just a quick reminder that The Silver Wind is published today in an expanded and updated edition from Titan Books.

This is not simply a reissue. In fact, I would go so far as it say it’s a whole new book! This edition not only brings the original text together with the previously uncollected, associated stories ‘Darkroom’ and ‘Ten Days’, it also includes a brand new novella, The Hurricane, which delves deeper into the early life and apprenticeship of The Silver Wind’s mysterious mastermind, Owen Andrews.

The Hurricane was always central to my conception of The Silver Wind as a whole. I wrote several versions of it back in 2010, but none of them truly satisfied me and so in the end I decided to go ahead and publish the book as it stood. When Titan approached me last year with the idea of relaunching The Silver Wind I was thrilled, not only because this new edition would introduce the work to a wider audience, but also because I would finally have the opportunity to present the text to readers in a form that more accurately represents my original vision.

The Silver Wind is important to me. Not only do I love these characters and their overlapping stories, they were written at a time when I was actively beginning to get a grip on what I wanted to achieve as a writer. As such, I would count The Silver Wind as my first significant work. It was a joy to finally bring all its constituent parts together, to edit and revise the book as a single entity. I am proud of the result and endlessly indebted to the team at Titan for making this new edition a reality.

I hope new readers enjoy accompanying Martin Newland on his journey(s). To those who read and liked the original version, please do consider investing in a copy of this new and definitive edition. I would never normally encourage book duplication just for the sake of it, but in this case I’m trusting you will find the outlay worthwhile.

If Julia Lloyd’s magnificent cover art isn’t enough to tempt you, I don’t know what is!

This week sees my debut as a book critic for The Guardian, with the appearance of my review of Stephen King’s new novel The Institute.

Taking on the King so publicly might have been daunting had it not been so interesting. Reading and reviewing his latest book encouraged me to contemplate – more even than usual – what exactly it is about this particular author that provokes such fierce reactions, be they of fanatical loyalty or chilly contempt. More even than that, what does King mean to me?

I have a long history with King, but that history is unusual in that it begins much later than is apparently the norm for most King devotees. I did not read him at all as a teenager – I remember pouring scorn on my brother’s dog-eared copy of Pet Sematary, and on my brother for reading what I ignorantly insisted must be trash – and it wasn’t until I was in my mid-thirties, and becoming a writer myself, that I began to understand for myself some of the many qualities that make King’s work unique in the speculative canon.

Two things happened more or less simultaneously: first, a record company rep I knew began passing on to me the promotional copies of King audiobooks he had taken to reading on his regular driving routes. Then, as a beginning horror writer eager to learn everything and then some about the field, I stumbled across King’s personal history of horror in the 20th century, Danse Macabre.

That book changed my life. Not only did it help to bring a semblance of order to my thoughts about horror, not only did it introduce to me a bunch of important writers previously unknown to me, it revealed to me also how well King writes, how uncannily closely his imagination and intellect are in tune with one another. Most of all, how his voice is, quite literally, inimitable. I remember listening to Rose Madder on audio while decorating my living room, thrilled by how completely I had become immersed in the intricacies and detail of that story. That King was one of the narrators of that particular audiobook no doubt affected the way I read and hear him to this day. His emphasis on particular phrases, often repeated, his ear for dialogue, his understanding of and love for certain tropes. All of this spoke to me powerfully, because it convinced me more or less in an instant that King knew what he was doing, not just in a narrative sense but in an ironical, metafictional sense. That his approach to fiction went way beyond story and deep into Story.

I fell in love. Rose Madder is not a popular work among King’s Constant Readers, but I am fiercely protective of it, still. My journey as a King fan had begun.

I raced through much of the back catalogue at that point. I loved what the King commentariat think of as the core works – I think Salem’s Lot is a classic of the twentieth century, I’m still spasmodically arguing with Chris over just how great Misery is (again, it’s classic) still regretting the presence of ‘that one stupid chapter’ in the otherwise masterfully epic IT. Already though my personal preferences were becoming tinged with unorthodoxy. I am one of the possibly three people who believe that Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining is actually deeper and stranger than King’s original. I prefer Four Past Midnight to Different Seasons. I like From a Buick 8. My favourite King work ever is Hearts in Atlantis.

No one who knows my writing will be surprised to discover the affection in which I hold the paired Bachman/King novels The Regulators and Desperation. But I know I’m going to lose company with all of you when I confess that for me, King’s scariest novel to date has been (yes, I’m going to say it) The Tommyknockers.

Second-favourite King novel? The Gunslinger, which contains some of his finest writing ever.

Favourite King short story? ‘Dolan’s Cadillac’. (I laughed right along with him.)

Favourite King-on-screen that isn’t The Shining? Storm of the Century (I’ve watched it four times and counting).

Most recent almost-masterpiece? Revival, which is destroyed, and I mean destroyed, by a denouement that might as well have been cribbed from a rejected screenplay of ‘The Rats in the Walls’. (Honestly Steve, there are times you break my heart.)

Unlike so many, I did not read King young, but I read him at a time of huge importance in my life, and I am in no doubt he has left his mark on me as a writer in ways I am only partially aware of. It is King’s sense of the possible, most of all, that marks him out, his eye for the marvellous, which exists everywhere, and often makes itself known when you least expect it. His sense of the numinous. His love of stuff. The way he’ll over-pad a novel till it strains at the seams and yet still make you feel obsessed by whatever he’s talking about.

As readers and as writers, King offers back to us the world we live in, subtly changed and ripe for exploration. My favourite parts of The Institute? The irrelevant bits, of course: Tim Jamieson’s convoluted route to becoming a night knocker deep in the boonies, Luke’s escape and epic train journey, which reminds me of Rosie’s flight from her killer cop husband all those years ago. King’s plots may be propulsive, but it is the details that make them compelling, the detours and sidetracks, the moments that stick in the mind like authentic memories.

I’m often critical of King – because he writes too much too quickly, because he falls back too willingly on generic tropes where more subtle and elusive solutions would prove more satisfying, because he too often breaks his own rule and lets us see the monster. My dissatisfaction with certain aspects of his work, sometimes with entire novels (Lisey’s Story, I’m looking at you) never detracts from my enjoyment of his achievement as a whole, my pleasure in the very fact that it exists. There are not so many writers whose privilege it is to leave such a lasting impression on us, or to excite such debate. It’s good to have him around.

Long live the King.

Still Worlds Turning is an anthology of new contemporary short fiction edited by Emma Warnock and published by No Alibis Press, an independent imprint run from a bookshop of the same name in Belfast. This was one of the books I decided to take with me to read at Worldcon, due to its firm (though by no means exclusive) focus on Irish writers.

Anthologies are strange beasts. At their best, they are genuinely eye-opening. At their worst, they are shapeless, uneven in quality and, occasionally, pointless. As with single-author collections, my taste in anthologies is very much for those that have a coherence about them, not necessarily in terms of theme (themed anthologies can quickly lose their appeal) but in terms of approach. They should have something to say, in other words – a sense of direction, a message to communicate about the state of fiction now.

Happily, Still Worlds Turning has all the radicalism and cohesion you could possibly wish for. Reading it is like being a fly on the wall at a gathering of talent so fresh and so furious it is almost gladiatorial.

Some of the writers included – Eley Williams, Joanna Walsh, Wendy Erskine, Sam Thompson, Jan Carson, Lucy Caldwell – were already familiar to me, the others new names. The quality was consistent throughout and while the the editor has deliberately shied away from imposing any overarching theme on Still Worlds Turning, what these stories have in common is a rawness and intensity of approach, a willingness to wrestle with the stuff of language. In the hands of these writers, the short story is cast not as a precious jewel, refined and entire unto itself, but as a living drama constantly evolving before our eyes. There is humour here, and pathos, where humour is a defining feature of resilience.

And for those who are into theme, it is there to be found. No doubt it was my own gothic sensibilities that led me to discern in this anthology a through-thread of the uncanny, not just in Sam Thompson’s appropriately named ‘Seafront Gothic’, but also in Lucy Caldwell’s disturbing and eerie ‘Night Waking’, Daniel Hickey’s brilliant and brutal – and very funny – ‘The Longford Chronicle’ (think/dream Boris Johnson meets The Hunger Games), Laura-Blaise McDowall’s strange and lovely ‘Balloon Animals’, and Mandy Taggart’s poignantly Faustian ‘Burn’.

There are stories here that I found challenging, not so much in the way they are written but in the vision they present. Judyth Emanuel’s ‘Tw ink le’, Jan Carson’s ‘The World Ending in Fire’, Dawn Watson’s ‘The Seaview Hundred and Fifty-Two’ and Lauren Foley’s ‘Molly & Jack at the Seaside’ in particular are viscerally raw snapshots of life at the margins but I count this very much as a plus because these are stories that need to be heard. I would point readers towards Lauren Foley’s account of Molly’s journey to publication for a sobering insight into how difficult it can be – still – to find publishers willing to take the risk with uncomfortable material, even when the editors themselves profess admiration for the work.

No Alibis and Emma Warnock should be commended for taking that risk. Still Worlds Turning deserves notice as a key reference point for what is happening in fiction right now. Here is a generation of writers delving deep into issues of community, poverty, sexuality and trauma whose work does not just feel timely, it feels urgent. Above all, these are stories that demonstrate the power and the beauty of language, in which the gaps in language say almost as much as the words themselves, in which form is as vital as content. Read and learn.

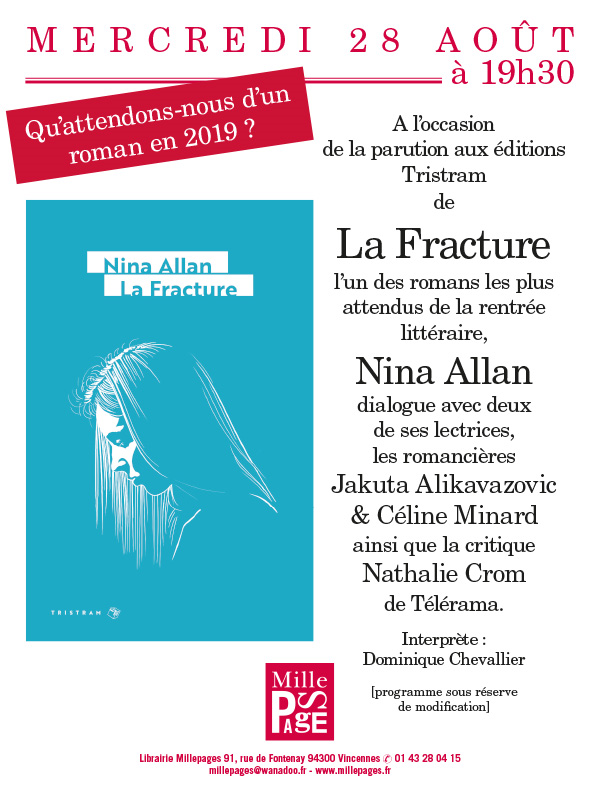

Just a reminder for anyone who happens to be in or around Paris this week that I shall be launching the French edition of The Rift, La Fracture, at Millepages bookstore in Vincennes at 19:30 this coming Wednesday.

I shall be in conversation with Nathalie Crom of the French literary and cultural magazine Telerama, and the evening will also feature an interview with the writer Jakuta Alikavazovic, whose fourth novel Night as it Falls will be published in the UK by Faber next spring, thus making her work available to an English-speaking audience for the first time. I am so excited to meet her!

The event has been organised by my amazing French publishers Editions Tristram and I cannot thank them enough for their steadfast commitment to my work and for their faith in me. Huge thanks are also due to graphic designer Thierry Dubreil, for creating the beautiful cover art for La Fracture, and to my translator Bernard Sigaud, who is irreplaceable. It’s a genuine thrill to be bringing The Rift to French readers, and of course to be returning to Paris, the setting for my 2018 story ‘The Gift of Angels’. Hope to see you there!

I was trying to ask her in a roundabout way if it was worth it. We felt the same nothingness, of that I was sure. But I wanted to see if she knew we were going to be okay or not. Or, at least, if I was. I was asking life advice, couched in the language of suicide, from a friend in a mental hospital. This was the direction my life had taken.

I picked up this book just prior to going to Worldcon. My choice was no accident. I’ve been enjoying reader reviews of The Pisces for some months now – the way this novel has divided opinion has made me insatiably curious about it – and I thought it would be a suitable companion for my first trip to Ireland. I wasn’t wrong. ‘Perfect summer read’ is not the kind of descriptive language I would normally go in for but in all the best possible ways – it’s set in California, it’s about a holiday romance with a merman – The Pisces is exactly that.

Magical, provocative, hilarious. I loved this book so much more than I ever expected to.

Lucy has accidentally broken up with her boyfriend, Jamie. She’s also stuck – interminably stuck – on her doctoral thesis, an exploration of silence in the work of Sappho. When her sister Annika suggests she spend the summer dog-sitting at her home in Venice Beach, Lucy can’t think of a reasonable excuse to say no, not even when Annika enrolls her in a group therapy circle attended by women driven to distraction by their pursuit of unavailable men.

It is only when Lucy meets Theo that the stage is set for romance of a more mythic variety. Is Theo simply the best sex of her life, or the embodiment of what Lucy, Sarah, Claire and maybe even Dr Jude are all secretly looking for: perfect love?

Negative critics of The Pisces seems to fall into two distinct brackets: those who dislike the explicit and occasionally startling portrayal of sex and the body that characterises the first half of the book especially, and those who find the characters – Lucy especially – unlikable and ungenerous. There is no doubt that the tone of Lucy’s narrative is bracing, not to say caustic, but rarely have I found a novel or a protagonist that speaks so honestly and with such deft, dark humour about what it is really like for a woman to grow up and come of age in a society which values her attractiveness to men, her ability to get and keep a man – scrap that, shall we just say MEN? above all else.

Such a (hilarious) relief, to see men – naked – through the female gaze for once. So poignant, such a vindication to have the corrosive effects of love addiction and the low personal esteem at its root dragged out into the open.

If some have called The Pisces savage and unfeminist, I call it savagely healing and one of the most unapologetically feminist novels I’ve read.

That the novel simultaneously plays out as a mysterious and satisfying work of speculative fiction makes it doubly pleasurable. As an examination of the habits of mer-people – how they see themselves reflected in our literature and through the lens of the human gaze – The Pisces is a delight, a ludic romance of ideas and mythology. Our discovery that Theo’s siren call turns out to be just that – a calculated seduction, a descent into delusion with potentially deadly consequences – leads us ultimately towards an ending that feels rewarding and true.

It makes a certain kind of sense to group this book with recent novels by Ottessa Moshfegh (My Year of Rest and Relaxation) Laura Sims (Looker) and Halle Butler (The New Me) – novels that have all boldly examined the female condition from the inside out. What makes The Pisces my favourite of an exceptional bunch is its leap into the vaster spaces of the fantastic. Lucy’s thoughts on Sappho are marvellously rendered, the novel’s understated satire on the self-serving nature of academe both delicious and accurate. The Pisces was a delight for me in every way, a further revelation of the versatility and imaginative richness of speculative ideas.

I booked my membership for the Dublin Worldcon when I came back from Paris in the autumn of 2017, so this con feels like it’s been a long time coming. At the centre of what has turned out to be a remarkably busy August, here is my schedule of events according to the programme:

Friday August 16th 12:00 Wicklow Room 1 – When Good Futures go Bad: dystopia as horror fiction

It’s not just for science fiction any more! How do horror dystopias differ from those in SF, and what are some examples, old and new, that we should be reading? {David Farnell, Pat Cadigan, Tim Major, Emil-Hjorvar Petersen.)

Friday August 16th 14:30 Point Square Stratocaster BC – Unwritable Stories

Every author has that perfect story that just refuses to be written. From wilful characters to wandering narratives and gaping plot holes, our panellists share the stories that would have even defied the Greek muses themselves. What made these stories so hard to write? What traps did they hold? And whatever happened to those old untold tales? Will they ever see the light of day or will they remain locked away in a hidden drawer? (Michael Swanwick, Karen Haber, Jacey Bedford, Jay Caselberg.)

Saturday August 17th 15:00 Wicklow Room 3 – What I Learned Along the Way

Writing is a many wondrous thing filled with highs and lows, but those lows can be really tough to navigate either after a great success or after a lack of success. Rejection is something every writer has to face, but how do writers keep writing in the face of failure? What lessons have they learned along the way? Our panellists share the ups and downs of a writing life. (Ian R. Macleod, Aliette de Bodard, George Sandison, Karl Schroeder.)

Saturday August 17th 20:30 Liffey Room 3 – Reading

I shall be reading from The Dollmaker – may contain elf queens…

My favourite convention to date has been the London Worldcon in 2014 and I’m certain Dublin 2019 is going to be its equal! The programme is looking excellent this year, with so much on offer for all segments of the science fiction community along every axis of interest. I am hoping in particular to get along to some of the ‘physics for writers’ panels, so I can stock up on hints and tips for future projects.

My first time in Dublin – my first time in Ireland, in fact – and I’m eager to check out some of the bookshops, museums and restaurants as well as catching up with SF ‘family’ and friends. If you’re around, please come and say hi. Here’s to the Irish Worldcon, and see you in Dublin!

© 2024 The Spider's House

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑