… and what better time to finally catch up with a classic of weird fiction that I have read a lot about but never read?

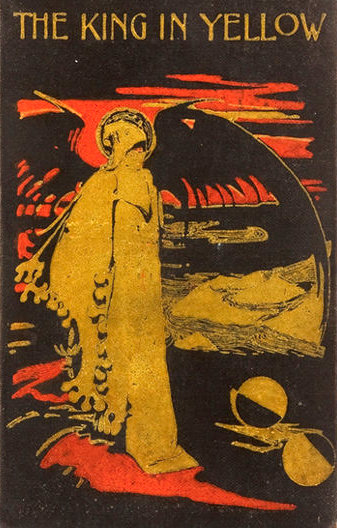

Robert W. Chambers’s The King in Yellow is one of those books. Written in 1895, this collection of stories has inspired and influenced writers all the way from HP Lovecraft to Nic Pizzolatto (and can you believe it has already been ten years since the first showing of True Detective??)

‘The King in Yellow’ is the title of a text-within-the-text, a play that brings insanity on anyone who reads it. I find it remarkable and rather wonderful, that the ‘cursed text’ trope is a hundred years old and more. So much of the power of the weird lies in its timelessness, the enduring appeal of its ideas and imagery. In the first story, ‘The Repairer of Reputations’, Hidred Castaigne is obsessed with the forbidden play, which he has read while convalescing from a head injury sustained in a horse-riding accident. Whether his madness stems from this accident or from reading ‘The King in Yellow’ is for the reader to decide. The glorious uncanniness of the story hinges on the fact that as readers we are drawn into Hildred’s delusion – that he is heir to a vanished kingdom – that we experience both shock and horror as his plan to assassinate his cousin in pursuit of his destiny comes closer to being enacted.

That the story is also science fiction – it is set twenty years in the future – adds another level of weirdness. The ‘future’ Chambers imagines is dark and sinister. There are suicide booths on street corners, a palpable sense of unease even in the most ordinary actions and interactions. All colours seem heightened, somehow. What I loved most about this story is how modern it feels.

Only the first four stories in the volume are explicitly bound by the ‘King in Yellow’ mythos. The remaining tales have often been dismissed or excluded from newer editions for not being weird enough, but I think this is a mistake. They are weird – very. There is a time-slip romance – a young man loses his way and ends up betrothed to a falconer in mediaeval France (very reminiscent of Le Grand Meaulnes) – and a brutal war story set during the Siege of Paris, which took place just twenty-five years before The King in Yellow was written. The chaos of war is written as a kind of haunting:

The fog was peopled with phantoms. All around him in the mist they moved, drifting through the arches in lengthening lines, then vanished, while from the fog others rose up, swept past and were engulfed. He was not alone, for even at his side they crowded, touched him, swarmed before him, beside him, behind him, pressed him back, seized and bore him with them through the mist.

Even in those stories where ‘lost Carcosa’ is not explicitly named, there is a sense that the realm of the lost king is there, waiting to reassemble itself, that the world we inhabit is the delusion, a temporary structure that might be swept away at any moment:

From somewhere in the city came sounds like the distant beating of drums, and beyond, far beyond, a vague muttering, now growing, swelling, rumbling in the distance like the pounding of surf upon the rocks, now like the surf again, receding, growling, menacing. The cold had become intense, a bitter piercing cold which strained and snapped at joist and beam and turned the slush of yesterday to flint.

That the overt weirdness of the stories recedes, reined back in the later tales to a suggestion, a supressed memory almost, makes the collection as a whole still more memorable and mysterious.

So much is left unsaid and unexplained. As if the writing of the book was interrupted, or prevented. It is unsurprising to me, that so many writers since have fallen in love with its atmosphere and – I use the term in its truest sense – obscurity. That they have felt bound to explore the yellow kingdom for themselves.

I may well become one of them…