Fairy painting has existed for as long as fairy mythology, though as a genre it has come to be associated with its first great flowering in Victorian England. Various theories have been put forward as to why Victorian artists – and the Victorian public – showed such a fervent interest in the depiction of alien realms. Some suggest the fashion was tied up in the resurgence of enthusiasm for Shakespeare, and the consequent popularity of such plays as The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream in which fairies and the fairy world feature as salient characters. Others have seen the phenomenon as a form of escapism born out of the seismic social and environmental changes of the Victorian age. With rapidly increasing industrialisation and the growth of the suburbs, both artists and art lovers experienced a yearning for scenes and subjects that featured the natural world. The spiritual, mystical aspect of fairy paintings in some sense symbolised the innocence people felt they were losing, for some even seeming to act as a conduit between the living and the dead. There is also the possibility that fairy painting was seen by more forward-thinking Victorians as a way of beating the censor. Many of the bucolic scenes that form the bedrock of the genre reveal more than a tantalising glimpse of naked flesh, and are characterised by an openness about sexuality and physical attraction that would have been scandalous if the characters featured had not been fairies.

For this reason alone, it is no surprise that the artists of the pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, with their progressive approach to relationships and unconventional modes of living, showed a notable enthusiasm for fairy subjects. There were other artists who made a career specialism of fairy art, including Richard Doyle and his brother Charles, John Anster Fitzgerald, Joseph Noel Paton and most famously Arthur Rackham. Their paintings were characterised above all by jewel colours, translucent tonal effects and an intense focus on tiny details.

This delicacy of approach and emphasis on fairy-tale-like beauty has recently been taken up by the ‘new wave’ of immensely skilled and deeply imaginative fairy painters including Brian Froud, Terri Windling and Anne Sudworth. But perhaps the best known – and least understood – of all fairy painters is Richard Dadd, a nineteenth century artist who started his career as a prodigiously talented painter in the Victorian tradition and ended it in the asylum, painting scenes and subjects that owed more to the disturbed and ultimately unknowable landscape of his inner world than the pastoral idylls that form a defining feature of the genre as a whole.

Dadd is usually described as an outsider artist, a term that is often applied to those with no formal training and who have sometimes also suffered damage to their mental health. I’m not a big fan of the label, which is often used more as a form of gatekeeping – a way of subtly indicating who is and who is not worthy of being described as an artist, who is important enough to be classed alongside ‘real’ artists who studied at art school and know their way around the industry – than as a genuine attempt to engage with the characteristics and unique insights of art like Dadd’s. In the case of Dadd, it also erases the fact that he started out very much as an insider, admitted to the Royal Academy of Art at just twenty years of age. His talent was outstanding, and led directly to him being offered the commission that would alter his life forever.

In 1842, the gentleman traveller and former mayor of Newport Sir Thomas Phillips engaged Dadd as the official artist on an expedition he was planning to make through the nations of the southern Mediterranean and the Middle East, culminating in a voyage up the Nile amidst the wonders of Ancient Egypt. Dadd was in a fever of enthusiasm for the enterprise – his early paintings focus very much on re-imaginings of the ancient world, and in spite of his delicate constitution, the promise of seeing these scenes and places for himself was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity he could not forgo. Friends and witnesses say he worked in a kind of delirium, often remaining outside for hours in the boiling sun, in spite of being warned of the dangers, especially for a Westerner unaccustomed to the climate. He was encouraged to rest, to eat properly, But Dadd worked on.

And not even those closest to him fully realised how deeply he was being affected by the sights he saw. The multitudes of people, the unfamiliar customs, the poverty, the glaring new colours, the overabundance of detail and sensation were working a profound and cataclysmic change in the artist. At first, Sir Thomas and other friends of Dadd attributed the painter’s increasingly strange and violent behaviour to an attack of sunstroke. He was shipped home to England, where his father Robert accompanied him to Cobham, a quiet Kentish village that, his father believed, would be the perfect environment for his son’s recuperation.

Tragically, it was not to be. In August 1843, Dadd fatally stabbed his beloved father in a public park, having become convinced that Robert was the devil. After a brief time on the run, Dadd was apprehended, declared to be of unsound mind, and sentenced to spend the rest of his life in the Bethlem (later Broadmoor) hospital for the criminally insane. His doctors encouraged him to keep on with his art, and his greatest work, The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke, was painted in the asylum. He was judged in many ways to be the model patient, retaining much of the friendliness and enthusiasm for life of his younger years. He never did lose his paranoid convictions, however, believing to the end of this days that he was the servant of the Egyptian god Osiris, sent to do his bidding here on Earth. Contemporary psychiatrists and neuroscientists who have studied Dadd’s case have mostly concluded that he was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, a genetic inheritance that also affected other members of his family.

My own fascination with the life and work of Richard Dadd began with a postcard reproduction of The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke my mother had purchased on a visit to the Tate Gallery in London, where the original painting is kept. The postcard is not the ideal format for a painting as intricately detailed as the Fairy Feller, but still I was captivated. I already had a bit of a thing for fairy art, but Dadd’s approach was different from any I had previously encountered. His colours are understated, the dour greys and greens of a winter in the country. His fairies are unfriendly-looking and almost threatening. More even than that, they seem completely immersed in their own world, their own private business; looking in on them feels like a dangerous act of trespass.

A number of years later, and I was finally able to see the real painting, on display at the Tate. I was struck once again by its resistance to human scrutiny, the profusion of detail. Seeing the painting in the flesh also helped to make plain the hours and years of work Dadd had lavished upon his masterpiece. In contrast with the minute brush strokes and refined surfaces that characterise much of Victorian fairy painting, The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke is densely clogged and heavily textured, paint upon paint upon paint, as if to reflect the agony Dadd suffered in attempting to convey a vision so personal and so traumatic he could never escape its hold on him.

Dadd laboured for ten years, and still chose to leave the painting unfinished. Amidst the jostling figures, the tangled undergrowth there are scattered patches of canvas that remain bare of markings. That one of these lacunae is the fairy feller’s axe? We can read into that what we will. What must be plain to any viewer is the sense of enchantment, of time forever stilled that rises up from this painting. Dadd could not bear to let his vision go. In this sense at least, he is still with us.

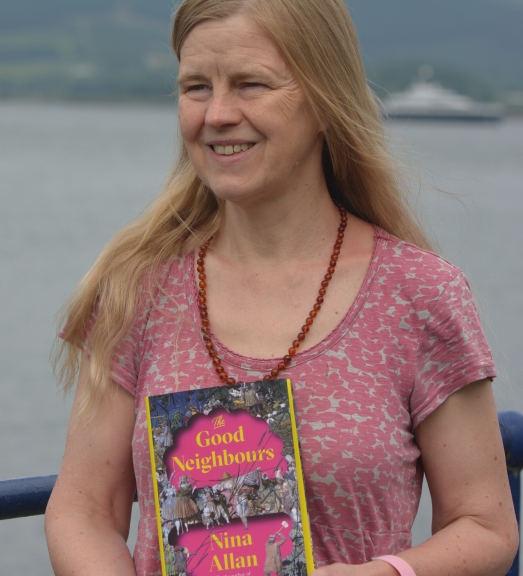

Almost from the moment I published my first story, I knew in my gut that at some point I would attempt to say something about Richard Dadd, to try and tell his story in a way that felt appropriate to his legacy. Dadd has left us with much to think about: the nature of genius, the traumatic fallout of mental illness, the sometimes fatal difficulty of trying to exist in a world that cannot tolerate difference. When I first began writing The Good Neighbours, I did not know that Richard Dadd would finally be making his appearance in the pages of my fiction. Which is not to say I was surprised when he chose to show up. Even today, information on Richard Dadd is scarce, and leaves many gaps, not least in relation to other members of his family. I feel certain there is more of his story to be uncovered. In the meantime, we have his paintings, and I can only hope that catching glimpses of them in The Good Neighbours will encourage more people to seek them out.

FURTHER READING:

Victorian Fairy Painting edited by Jane Martineau. A catalogue that was produced to accompany a 1997 exhibition at the Royal Academy, this lavishly illustrated book includes essays and a wealth of supplementary information from experts in the field. If you are into fairy art, this is a must-have!

Richard Dadd: the artist and the asylum by Nicholas Tromans. This is the most comprehensive biographical work on Dadd to date. Here you will find images of many of his most important paintings, including a series of enlarged plates that reveal The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke in full and extravagant detail.

Bedlam by Jennifer Higgie. An experimental novel that attempts to convey Dadd’s genius and breakdown through a series of poetic vignettes. Higgie is an art critic and editor and her approach to Dadd is powerfully felt. This is an essential work in the Dadd bibliography and deserves to be better known.

Come Unto These Yellow Sands by Angela Carter. Written in 1985 as a play for radio, Come Unto These Yellow Sands attempts to conjure the world of Richard Dadd by bringing his own fantastical creations verbally to life. I was lucky enough to catch a rare broadcast of this small masterpiece on Radio 3 in 2018, while I was still deeply engaged in the writing of The Good Neighbours. To my mind it comes closer than anything previously attempted in conveying both Dadd’s heightened state of consciousness and his tragic collapse. I wish the BBC would make this work of Carter’s permanently available. Luckily the full script is included in the anthology of Carter’s plays The Curious Room.