June 10th sees the publication of my fourth novel The Good Neighbours. By way of celebration, I’m going to be posting an essay a week through the month of June under the #FolkloreThursday hashtag, delving into the magic and mystery of the fairy mythology that forms one of the book’s defining strands. To begin, I’m going to cast an eye over humanity’s timeless obsession with the fairy world, as well as sharing a handful of my own favourite fairy fictions.

*

Most of us learn about fairies at an early age. It seems strange, when you think about it as an adult, that our parents and grandparents, from whom we most commonly hear our first fairy tales, are so eager to impart to their young children stories of an eldritch otherworld that might swallow them forever. A secret kingdom that exists in tandem with our own, from which magical beings might emerge to visit us, to spy on us as we sleep, to trick us into dangerous behaviours or, on occasion, to steal us for themselves. What were they thinking? we might ask ourselves now, even as we ourselves pass on similar stories to our own best friends, cousins, step-brothers, children or children’s children. Because fairy tales are strange tales, designed to give us pause for thought, structured to demand our deeper engagement with what we really believe, parables that teach us, more than anything, that appearances can be deceptive, that the world we see before us may be more than it seems. Such duality can be frightening. It teaches us that our human lives are built on shifting sands.

I loved – no, rather, I was obsessed with fairy stories from the time I could first understand them. Happy to consume dark, sordid tales such as The Snow Queen and Rumpelstiltskin alongside Arthur Rackham’s rapturous fairy paintings, Enid Blyton’s Your Book of Fairy Stories and Cicely Mary Barker’s Flower Fairies of the Garden, my first encounter with fairies in the real world came with the loss of my first milk tooth, and my parents’ immediate insistence that I offer it as a gift to the tooth fairy. You might get a reward, they hinted, and I can still remember the excitement I felt, slipping my hand beneath the pillow as I awoke, the feel of that bright piece of silver, different somehow from other money and what with that nagging mystery tugging at my brain – how on Earth could anyone get that coin under my pillow without waking me up? – it never occurred to eight-year-old me to wonder what were the fairies doing with all the teeth?? If I were to consider the question now, the story I would tell would have something to do with biological data capture, with the fairies’ collating of human code for nefarious purposes. And we give it over voluntarily, you see, that’s the horror of it. Our children’s DNA, sold for a shilling…

You can see how my imagination is apt to fly away with me, how the subject of fairies still exercises its mystical allure. As a writer, what I love about the fairy world is its dark ambiguity. Even as children, we learn that fairies grant wishes but they also throw curses, that lurking behind every fairy godmother is a bad fairy at the christening. Be careful what you wish for, in other words, and a deeper, more considered dive into fairy mythology reveals that the fair folk are neither good nor bad, only themselves. We humans are the alien invaders, clod-hopping beasts in a numinous realm we cannot hope to safely navigate, or understand.

I believe in fairies as the imaginative embodiment of the unknown, the kingdom we enter in dreams or glimpse at twilight from the corner of an eye, the promise inherent in all of art that there are other worlds than these. At a more prosaic level, fairies are symbolic of the fact that we often fail to notice what is under our noses. My first published story ‘The Beachcomber’ might be classified as a piece of fairy fiction. ‘Fairy Skulls’, written ten years after that, identifies itself. My fourth novel, The Good Neighbours, started out as a mystery novel loosely inspired by a family murder in the West Country. It was not until I began writing about Johnny Craigie, the taciturn carpenter who everyone has pegged as a murderer but who might just be a genius, that the little people – the Good Neighbours of the novel’s title – began inveighing themselves into the narrative, and I realised I had embarked upon a journey still more difficult and more mysterious than the one I’d first imagined.

It was almost as if I’d been tricked – pixie-led – into writing The Good Neighbours, as if the fair folk themselves were demanding to be included in what turned out to be, after all, their story.

Over the next few weeks I will be delving deeper into fairy mythology, exploring more of the works and ideas that make these stories so compelling and so perennial. In the meantime, I will leave you in the company of five of my favourite works of fairy fiction – disturbing and beguiling in equal measure, these are books to spirit you away to another world.

The Stolen Child by Keith Donohue. This 2006 novel tells the story of a boy who is taken from his home by fairies and forced to become one of a gang of changelings. These wayward creatures mature in mind as the years pass, though their bodies remain frozen in childhood, at the moment of their abduction. Henry Day, or Aniday as he is rechristened, roams the countryside in search of food and shelter, becoming increasingly forgetful of his human self. Meanwhile, the changeling left behind in his place begins to develop memories of a time before his abduction, when he had a place and a rightful future in the world of humans. Chilling, beautiful and poetic, Donohue’s novel was inspired by Yeats’s poem ‘The Stolen Child’, a magnificent piece of fairy fiction in its own right.

The Iron Dragon’s Daughter by Michael Swanwick. Jane is a human slave in a dragon factory managed by elves (which is all you need to know, right?) After forging a relationship with one of the sentient machines, she bands together with some other changelings and plots their escape. Released into a world of unstable factions and multitudinous dangers, Jane travels deep inside the fairy realm in pursuit of her true identity and ultimate purpose. Swanwick’s exploration of fairy mythology is dark and original and desperately real, made all the more frightening by the glimpses of our own world – Jane’s world – that are briefly offered up to us before being ripped away. The Iron Dragon’s Daughter is simultaneously a thrilling adventure and a philosophical investigation of reality itself.

The Good People by Hannah Kent. Kent’s second novel has its roots firmly in historical reality as we meet Nora Leahy, an Irish countrywoman who inherits the care of her grandson Micheal when her daughter tragically dies. Once a healthy, well developed child, the little boy who comes to live with her seems utterly changed, and utterly impervious to Nora’s desperate attempts to love and care for him. Convinced that her real grandson has been replaced by a fairy changeling, Nora enlists the help of Nance Roche, a local wisewoman, in forcing the fairies to return the boy. The results are horrific and disastrous for both women. Kent’s use of language in summoning a world of rural isolation – a world in which ancient beliefs and superstitions have as much influence on people’s everyday lives as the weather and the local priest – is a miraculous intersection between the keenly observed and the fearfully imagined. Most of all, her summoning of changeling mythology as a tool with which to interrogate the entrenched misogyny of the period makes The Good People an essential work of feminism as well as a cornerstone of fairy literature. I reviewed the book for Strange Horizons here.

Under the Pendulum Sun by Jeannette Ng. An original and marvellous twist on the missionaries in space trope, Under the Pendulum Sun gives us missionaries in fairyland. Laon Helstone has journeyed deep into Arcadia, the kingdom of the fae, in search of new understanding and new converts. Nothing has been heard from Laon in some time, and so his sister Catherine, desperate for news of him, decides to follow in his footsteps. Arriving at the castle of Gethsemane, Catherine finds herself a virtual prisoner, with the mansion’s strange and secretive inhabitants reluctant to reveal even the smallest amount of information about the whereabouts and wellbeing of her absent brother. Ng’s novel is one of the most interesting and well achieved fantasy debuts since Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell, drawing on classic gothic tropes, the lives and literature of the Bronte sisters as well as philosophy and theology to deliver a story that is striking in its literary ambition and in places genuinely chilling.

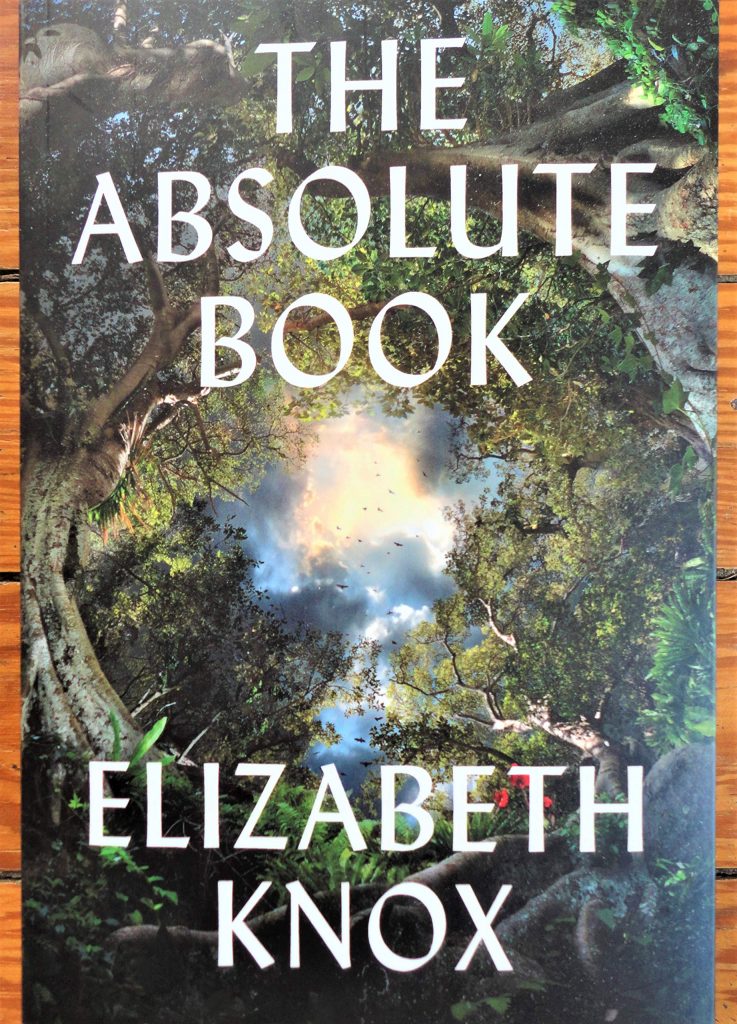

The Absolute Book by Elizabeth Knox. A modern, sharp-eyed take on some classic tropes, Knox’s epic takes us on a journey that sees the fairy realm invaded by demons with our own world held to ransom. Taryn Cornick is still desperately grieving for her dead sister. She believes Beatrice was murdered – but has no idea why. She especially has no idea about the finer details of her own past, or the true nature of the house at Prince’s Gate, from which all her most precious memories ultimately stem. Knox’s fairyland can be a dangerous place, but then so can our own world, and as Taryn struggles to overcome her own demons she is not always a safe person to be around. The Absolute Book is a rich and complex achievement, a new masterwork of fantasy, which I reviewed for the Guardian here.