The crab showed no reaction whatsoever, nor did it slacken its pace. Ignoring Jimmy completely, it walked straight past him and headed purposefully into the south. Feeling extremely foolish, the acting representative of Homo sapiens watched his First Contact stride away across the Raman plain, totally indifferent to his presence.

He had seldom been so humiliated in his life. Then Jimmy’s sense of humour came to his rescue. After all, it was no great matter to have been ignored by an animated garbage truck. It would have been worse if it had greeted him as a long-lost brother… (Arthur C. Clarke, Rendezvous with Rama.)

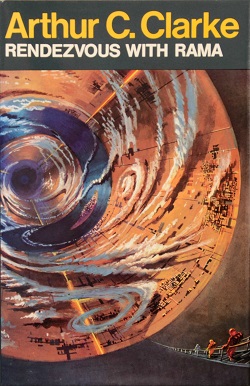

After my less than satisfactory experience with The Last Astronaut, I decided it might be interesting to revisit what I took to be that novel’s originating influence. I was curious to see not only how well the older book fared by comparison (I took comfort from the fact that it could hardly be worse) but also how well it stood up as a novel at a distance of forty-plus years since its publication. I was pretty sure I had read Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama during my late teens, along with a shipload other other classic science fiction both of that period and earlier, though I had almost literally no memory of it aside from the basic premise: an unknown object is detected entering the solar system, a team of astronauts are sent up to investigate. I hadn’t read any Clarke for decades anyway, so this rereading promised to be fascinating on several levels.

It is 2131, and humanity has founded settlements on several of the other planets in our solar system as well as their moons. When an interstellar object is detected beyond the orbit of Jupiter, satellite images reveal that it is not an asteroid, as previously imagined, but a perfectly cylindrical vessel, some fifty kilometres in length and clearly alien in origin. The unidentified craft is named Rama, after the Hindu god, and a party of astronauts leave Earth on a mission to discover what kind of threat – or otherwise – it might pose to human civilization. The Endeavour is commanded by William Norton, who in matters of personal integrity and exploratory zeal identifies strongly with the long-dead captain of his own ship’s much older namesake.

On entering Rama, the crew of the Endeavour are met with a series of marvels and mysteries that defy human understanding. They know their time on Rama is limited – the vessel will soon pass too close to the sun for the Endeavour to continue safely with its mission. Gathering as much information as they can, they must also contend with the increasingly hostile rhetoric of representatives from the planetary settlement on Mercury. The Hermians believe themselves to be at particular risk from Rama, and given the fact that the vessel’s intentions cannot be verified, they are minded to shoot first and ask questions later.

I felt certain The Last Astronaut had taken inspiration from Rama. I was unprepared for quite how much. The narrative trajectory of TLA follows that of Rama pretty much identically: the long and exhausting climb down into the vessel, the discovery of a breathable atmosphere, the melting ice, the gradual awakening of native life forms – everything, right down to the captains of both missions being the same age. Intentional homage or unpardonable laziness? I don’t know and frankly, aside from a feeling of mild to middling outrage on Clarke’s behalf, I don’t even care that much. If The Last Astronaut were a better book, these ‘coincidences’ might matter more. As things stand, The Last Astronaut is a disposable potboiler, while Rendezvous with Rama is deservedly a classic of Western science fiction. No argument over who wins this particular battle of the BDOs.

One embarks on reading older science fiction novels braced for an onslaught of square-jawed heroes and unpalatable opinions, but aside from one highly unfortunate likening of a crew member to a monkey, and one ridiculous and totally uncalled-for meditation on the motion of women’s breasts in zero gravity, Clarke does pretty well. He is consciously progressive in his treatment of sexuality – homosexual and polyamorous relationships are seen as normal in his 2100s – and women on board the Endeavour (the odd lapse into innuendo aside) enjoy not only equal status, but equal respect. In a particularly notable sequence, Sergeant Ruby Barnes, a master mariner, is granted control of the mission when members of the crew are suddenly threatened by an enormous tidal wave:

She’s magnificent, thought the Commander – obviously enjoying every minute, like a Viking warrior going into battle.

Not a hint of gendered language in sight, with Norton readily deferring to Barnes’s greater expertise. It is Ruby who makes the decisions here, proving how capable Clarke was of imagining women in positions of command. I also liked Clarke’s treatment of religious faith. One of the Endeavour’s crew members is a devout member of the Church of Christ Cosmonaut (Jesus was a spaceman, basically). Whilst Norton does not share his beliefs, he does not belittle them either; rather, he takes particular note of this crewperson’s integrity, commitment and logical approach in trusting them to undertake a crucially important and potentially hazardous manoeuvre at a critical time.

Just as impressive is the novel’s overall attitude towards alien life. The concept of the alien as hostile and/or disposable has become so much the norm within Hollywoodised media that as an audience we have become more or less inured to it. In The Last Astronaut, the wonders of 21 are ultimately of no account when set against the terrifying threat to Earth the vessel poses, a threat that must be destroyed – with enormous weapons – as noisily as possible. (And yes, if monstrous megaworms really were about to eat the planet then I’d be first to press the button, but it is important to remember that this is fiction and authors have choices.)

The life forms encountered in Rama are not only imaginatively drawn, they are also notable in that Clarke makes a proper attempt to describe creatures that are alien without being monstrous. The attitude of the crew towards these beings is also significantly refreshing. Even Jimmy Pak, ‘a man of action, not introspection,’ feels guilt over his purloining of a botanical specimen, and Norton is determined they do nothing to harm the Raman ‘spiders’ that invade their camp:

Training was one thing, reality another; and no one could be sure that the ancient, human instincts of self-preservation would not take over in an emergency. Yet it was essential to give every entity they encountered in Rama the benefit of the doubt, up to the last possible minute – and even beyond.

Commander Norton did not want to be remembered by history as the man who started the first interplanetary war.

What a relief and a delight, to travel with a crew whose first instinct is to observe rather than to interfere or destroy.. That the tripedal spiders and other ‘biots’ are allowed to remain essentially a mystery is also to Clarke’s credit. Rama is vast and time is short. At least for now, the secrets of this alien civilization must remain unknowable, a tactic that renders them immortal and endlessly alluring. The novel’s penultimate sequence, in which the crew of the Endeavour are briefly caught in the wake of this vast alien structure as it prepares to take on fuel for its onward journey, has a poetry and a grandeur that reduced me to tears.

It was dropping out of the Ecliptic, down into the southern sky, far below the plane in which all the planets move. Though that, surely, could not be its ultimate goal, it was aimed squarely at the Greater Magellanic Cloud, and the lonely gulfs beyond the Milky Way.

Rendezvous with Rama earns its classic status not just through its expert deployment of classic tropes but in its conscious invocation of classical archetypes. Clarke’s novel is an Odyssey, a hero’s journey in which the hero is Rama itself as much as Norton. The tests and trials we encounter along the way are provided not by hydra or sirens but by physics and maths, while the end of the journey transcends anything so simple as ‘closure’ precisely because the central mystery remains unsolved.

There will be those who argue that Rama is unsatisfactory as a novel through being more or less plotless; for me, the book’s imaginative reach, its stylistic economy, its ability to inspire debate makes that irrelevant.

We could have a long debate over how The Last Astronaut’s mirror-likeness to Rama might be justified or defined. It could be argued, for example, that Wellington’s novel is actually intended to be an anti-Rama – a deliberate examination of how the story might have played out had the alien vessel been actively hostile. I would counter that for such a strategy to be successful, The Last Astronaut would have to be Rama’s equal in terms of literary achievement. What is beyond doubt is that the quality of Clarke’s writing – marked by age in places yes, but always cogent, cleanly descriptive, economical and stylish – raises his novel to a level Wellington’s never approaches. Eschewing cheap thrills, Rendezvous with Rama is characterised throughout by that philosophical stateliness, that sense of rapt idealism and thirst for knowledge that has helped to define science fiction as a mode of literature.