We’ve spent most of this past week in Lincolnshire. Now well into his second draft of The Adjacent, Chris suddenly decided he really needed to visit the WW2 bomber bases at Coningsby and Scampton, territory that formed one of the main settings for The Separation and that features strongly again in the new book. And so we set off. I always derive huge benefits and excitement from visiting parts of the country that are new to me, and when the relatively simple act of travelling to somewhere unknown is combined with such weird and arresting experiences as sitting in the pilot’s seat of an old Canberra B6 or standing beneath the windows of the room where Guy Gibson and his squadron received their mission briefing for the Dam Busters raid, then these happenings pass from memorable to significant.

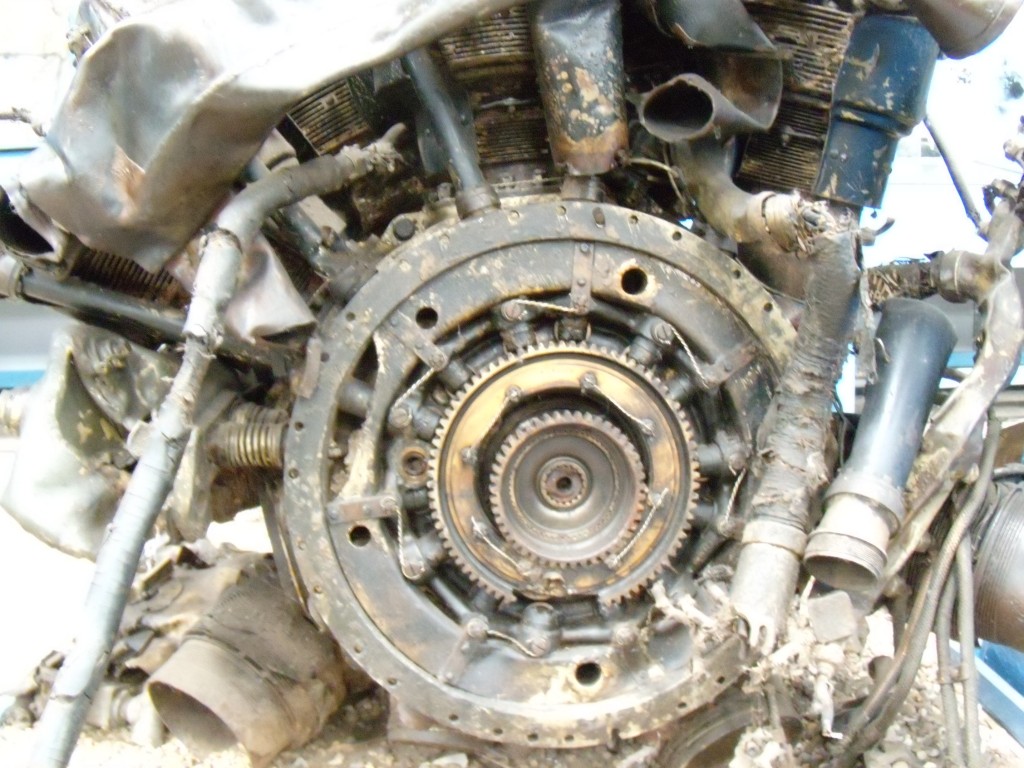

‘Bomber County’ is quietly, unassumingly beautiful, a place for hiding out and holing up. But reminders of what you might even call the bombing industry are everywhere here, and make thoughts of war and anger over it inescapable. Wandering around the vast hangars filled with historic aircraft and crash site excavations trying to get my own take on everything I came back again and again to the thought that once a war has been fought what we are mostly left with is twisted and rusting machinery and the stories, which become legends, of the courage and forbearance of those individuals who fight or suffer war’s oppressions and privations. The rest – the politics and rationale behind every war – is ultimately proved mendacious or misguided.

An intense and intensely valuable couple of days, not least because for a writer it’s impossible not to want to respond on some level. Trips like this yield stories, inspirations that are often different from those that seem more immediately discernable.

The trick is to wait.

Returned to the news that Dietrich Fischer Dieskau has passed away. I can scarcely believe it.

A wonderful book with a very personal take on WW2 is Daniel Swift’s Bomber County, the story of one man’s search for his lost grandfather and the lives and experiences of the Allied airmen as revealed through poetry. I really can’t recommend this highly enough.

Fischer Dieskau is probably most famous for his interpretations of Schubert, but his repertoire was vast, his knowledge and understanding of the German Lied completely unique. Fortunately we’ll be able to go on treasuring this and drawing on it through the legacy of his recordings. I’ve been listening to him this morning in a recording of ‘Firnelicht’, a song from a little-known Lieder cycle called Berg und See by Othmar Schoeck. The song is about a Friedrichian ‘Wanderer’ as he thrills to the strange radiance, the particular light of the mountains. Thinking about Fischer Dieskau today, the words of the last verse seem particularly appropriate.

What can I do for my country before I go to rest in my grave? What can I give that will outrun death? A word perhaps, perhaps a song. A still, small Shining.

(The words are by Conrad Meyer 1825-98.)

Was kann ich für die Heimat tun, bevor ich geh im Grabe ruhn? Was geb ich, das dem Tod entflieht? Vielleicht ein Wort, vielleicht ein Lied, ein kleines stilles Leuchten!