‘The poem, like most of my poems, and like the story I’d promised to expand, conflated fact and fiction, and it occurred to me – not for the first time, but with a new force – that part of what I loved about poetry was how the distinction between fiction and nonfiction didn’t obtain, how the correspondence between text and world was less important than the intensities of the poem itself, what possibilities of feeling were opened up in the present tense of reading.’

(Ben Lerner, 10:04)

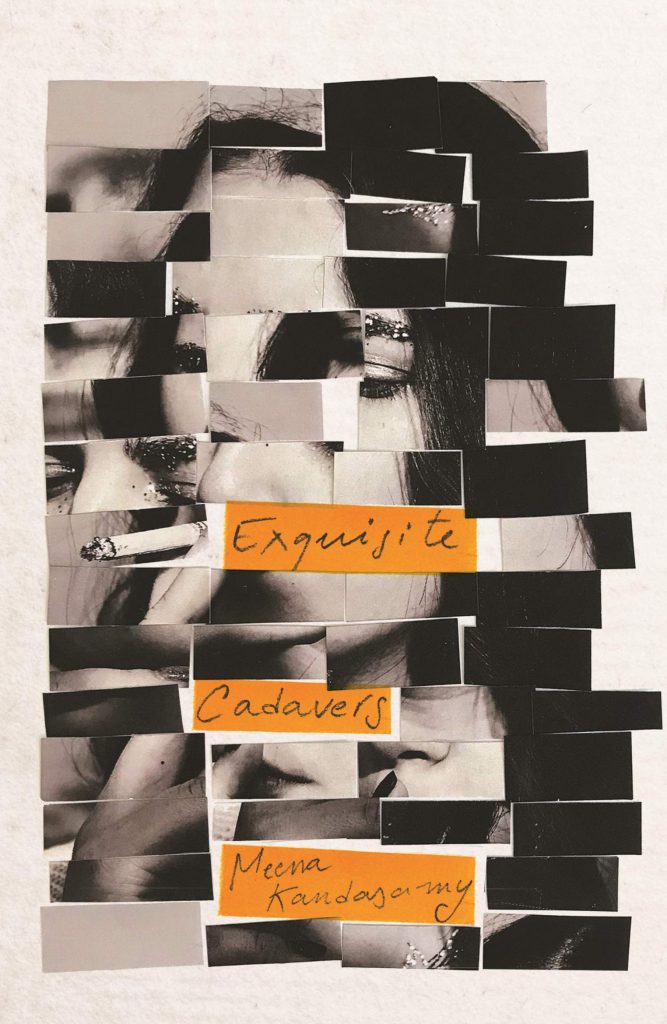

In a recent episode of BBC Radio 4’s Open Book, an interview with the American writer Ben Lerner about his new semi-autobiographical novel The Topeka School could be heard back-to-back with a discussion between Olivia Sudjic and Meena Kandasamy on the nature and rise of autofiction. I read Sudjic’s Exposure earlier this year. At the time of listening to the programme I had just finished reading Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04 in preparation for reading The Topeka School. As I write these words now, I turned the final page of Kandasamy’s third novel Exquisite Cadavers about half an hour ago.

Kandasamy has spoken of how Exquisite Cadavers is in part a response to the response surrounding her second novel, When I Hit You, much of which had the effect of relegating this singularly audacious, virtuoso autofictional essay on the radical power of literature to the domain of misery memoir. As part of the discussion on Open Book, Kandasamy was upfront about the repeated frustration she has experienced in being subjected to this kind of commentary:

‘When I wrote my second novel and it was very personal, people would reduce the whole thing to “oh, she just wrote about what happened to her”. Most of the emphasis was on the ‘what happened to her’ part of it, as opposed to the fact that ‘she wrote about it, and she’s creating a work of art here’. The fact that you’re a woman, the fact that this is an artistic endeavour that’s taken years to write is just erased.’

Sudjic was quick to confirm that her experience as a writer has thus far been very similar and I could have listened to their conversation for hours:

‘Autofiction when it’s written by women is often seen as this indulgent thing where they’re writing about themselves, and I find that so strange, because what they’re really doing is drawing attention to the frame. It’s a technique that sits next to metafiction really, which is drawing attention to how it’s all constructed, and I find it very frustrating that that’s what gets ignored when it’s women doing it, whereas for example with Ben Lerner, everyone’s very on board with reading those books as real, structural, artistic works, rather than constantly asking him what his mother thinks about the way she’s represented in them.’

Exquisite Cadavers is a brave and important work on so many levels. With a structure partly inspired by Derrida’s 1974 novel Glas, it presents a fictional story of a mixed-race couple living in contemporary London alongside margin notes detailing the ideas, events and research that inspired it. As the book progresses, the invented story and the autobiographical elements begin in their own strange way to coalesce, each illuminating the other in a way that reads as a genuine representation of the way fiction is actually created. It’s a brilliant achievement, and what I love most about it – as with When I Hit You – is its visceral revelation of the power literature can still wield, not in spite of its ‘literariness’, but because of it. The ‘lived experience’ is the creation of these words, these sentences, this body of work, not the facsimiles of experiences described, which may or may not be ‘true’ but who the hell cares? What we care about is what is on the page, the experience that brings reader and writer closer together.

The irony, as Sudjic points out, is the extent to which she and Lerner and Kandasamy are engaged in similar literary endeavours, as set against the peculiar distance that is drawn between them by many readers and commentators. I loved Lerner’s first two novels so much I found myself weeping in gratitude. I cannot imagine a more important writer right now than Kandasamy. I found Sudjic’s polemic in Exposure vitally enlightening and, safe in the knowledge that her second novel Asylum Road is coming down the line soon from Bloomsbury, I am about to begin reading her debut, Sympathy.

I’m saving The Topeka School for the week between Christmas and Hogmanay. Far from being played out, the novel today is more exciting than it’s been for years.