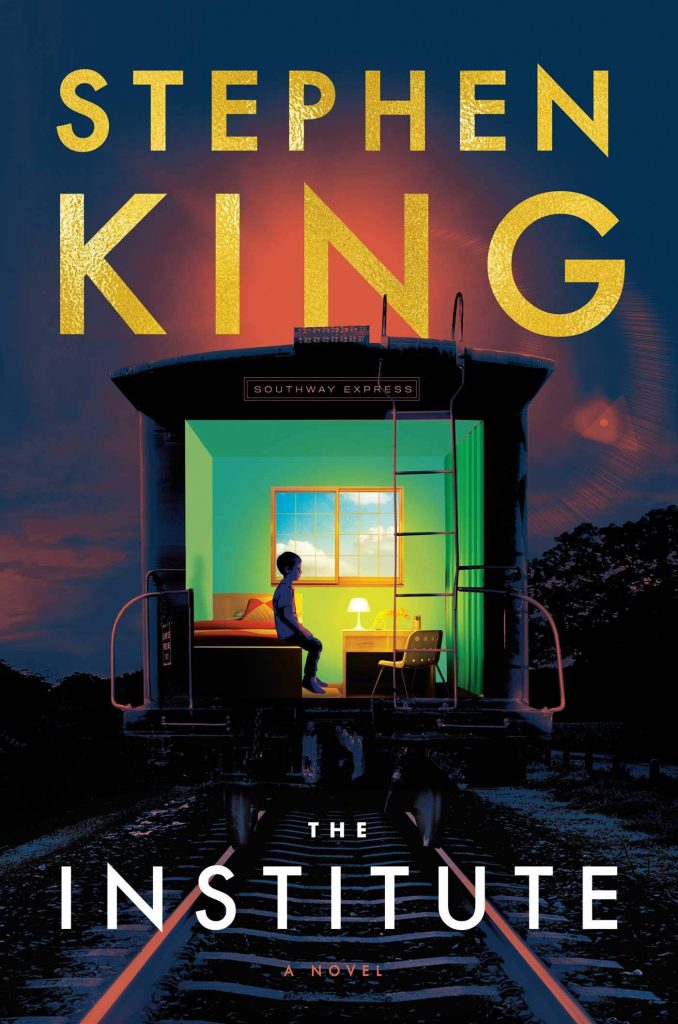

This week sees my debut as a book critic for The Guardian, with the appearance of my review of Stephen King’s new novel The Institute.

Taking on the King so publicly might have been daunting had it not been so interesting. Reading and reviewing his latest book encouraged me to contemplate – more even than usual – what exactly it is about this particular author that provokes such fierce reactions, be they of fanatical loyalty or chilly contempt. More even than that, what does King mean to me?

I have a long history with King, but that history is unusual in that it begins much later than is apparently the norm for most King devotees. I did not read him at all as a teenager – I remember pouring scorn on my brother’s dog-eared copy of Pet Sematary, and on my brother for reading what I ignorantly insisted must be trash – and it wasn’t until I was in my mid-thirties, and becoming a writer myself, that I began to understand for myself some of the many qualities that make King’s work unique in the speculative canon.

Two things happened more or less simultaneously: first, a record company rep I knew began passing on to me the promotional copies of King audiobooks he had taken to reading on his regular driving routes. Then, as a beginning horror writer eager to learn everything and then some about the field, I stumbled across King’s personal history of horror in the 20th century, Danse Macabre.

That book changed my life. Not only did it help to bring a semblance of order to my thoughts about horror, not only did it introduce to me a bunch of important writers previously unknown to me, it revealed to me also how well King writes, how uncannily closely his imagination and intellect are in tune with one another. Most of all, how his voice is, quite literally, inimitable. I remember listening to Rose Madder on audio while decorating my living room, thrilled by how completely I had become immersed in the intricacies and detail of that story. That King was one of the narrators of that particular audiobook no doubt affected the way I read and hear him to this day. His emphasis on particular phrases, often repeated, his ear for dialogue, his understanding of and love for certain tropes. All of this spoke to me powerfully, because it convinced me more or less in an instant that King knew what he was doing, not just in a narrative sense but in an ironical, metafictional sense. That his approach to fiction went way beyond story and deep into Story.

I fell in love. Rose Madder is not a popular work among King’s Constant Readers, but I am fiercely protective of it, still. My journey as a King fan had begun.

I raced through much of the back catalogue at that point. I loved what the King commentariat think of as the core works – I think Salem’s Lot is a classic of the twentieth century, I’m still spasmodically arguing with Chris over just how great Misery is (again, it’s classic) still regretting the presence of ‘that one stupid chapter’ in the otherwise masterfully epic IT. Already though my personal preferences were becoming tinged with unorthodoxy. I am one of the possibly three people who believe that Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining is actually deeper and stranger than King’s original. I prefer Four Past Midnight to Different Seasons. I like From a Buick 8. My favourite King work ever is Hearts in Atlantis.

No one who knows my writing will be surprised to discover the affection in which I hold the paired Bachman/King novels The Regulators and Desperation. But I know I’m going to lose company with all of you when I confess that for me, King’s scariest novel to date has been (yes, I’m going to say it) The Tommyknockers.

Second-favourite King novel? The Gunslinger, which contains some of his finest writing ever.

Favourite King short story? ‘Dolan’s Cadillac’. (I laughed right along with him.)

Favourite King-on-screen that isn’t The Shining? Storm of the Century (I’ve watched it four times and counting).

Most recent almost-masterpiece? Revival, which is destroyed, and I mean destroyed, by a denouement that might as well have been cribbed from a rejected screenplay of ‘The Rats in the Walls’. (Honestly Steve, there are times you break my heart.)

Unlike so many, I did not read King young, but I read him at a time of huge importance in my life, and I am in no doubt he has left his mark on me as a writer in ways I am only partially aware of. It is King’s sense of the possible, most of all, that marks him out, his eye for the marvellous, which exists everywhere, and often makes itself known when you least expect it. His sense of the numinous. His love of stuff. The way he’ll over-pad a novel till it strains at the seams and yet still make you feel obsessed by whatever he’s talking about.

As readers and as writers, King offers back to us the world we live in, subtly changed and ripe for exploration. My favourite parts of The Institute? The irrelevant bits, of course: Tim Jamieson’s convoluted route to becoming a night knocker deep in the boonies, Luke’s escape and epic train journey, which reminds me of Rosie’s flight from her killer cop husband all those years ago. King’s plots may be propulsive, but it is the details that make them compelling, the detours and sidetracks, the moments that stick in the mind like authentic memories.

I’m often critical of King – because he writes too much too quickly, because he falls back too willingly on generic tropes where more subtle and elusive solutions would prove more satisfying, because he too often breaks his own rule and lets us see the monster. My dissatisfaction with certain aspects of his work, sometimes with entire novels (Lisey’s Story, I’m looking at you) never detracts from my enjoyment of his achievement as a whole, my pleasure in the very fact that it exists. There are not so many writers whose privilege it is to leave such a lasting impression on us, or to excite such debate. It’s good to have him around.

Long live the King.