I don’t think it is any coincidence at all that we are living through a new golden age of horror fiction. In a recent review of Jac Jemc’s well-nigh perfect work of rural unease, The Grip of It, I recalled the horror boom of the seventies and eighties, kick-started by the publication of Stephen King’s debut novel Carrie in 1974, spluttering to a halt in the 1990s through massive grunge overload. The ultimate effect of this boom-and-bust on horror writers was pretty disastrous, leading as it did to an extended period – twenty years, more or less – during which it was practically impossible for even the best writers to sell a horror novel.

Looking back on that period now, we can observe how horror did not actually go away, but rather evolved. The Stephen King brand of horror – let’s call it baby boomer horror – focused closely and brilliantly on small town anxieties, childhood trauma, the undermining of common decency through unholy powers. It reflected the anxieties of its age, in other words – the violent overthrow of old certainties, the dawning of new perils in a post-Hiroshima, post-Vietnam world. We see this clearly in the American horror cinema of the time – John Carpenter’s Halloween, Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, George A. Romero’s zombie movies – which closely parallels the themes and style of King’s fiction. Much has been written about how the 70s boom degenerated into splatterpunk and died – for more on this do read this excellent essay by Steffen Hantke on the Dell Abyss series (and please read Kathe Koja’s The Cipher if you haven’t already) – but what actually happened, eventually, was that 70s horror and its small-town ambience bifurcated into urban fantasy on the one hand (think Buffy, Twilight, Neverwhere) and the serial killer thriller on the other. While both these trends are still very much with us, they have done what trends do and become established, therefore comfortable. We know what to expect from them and – continue to enjoy them as we might – in terms of what is new now in horror fiction they have little to offer.

In the wake of the splatterpunk implosion, horror literature became a no-go zone for mainstream publishers. You could still buy King and Koontz, but everyone else interested in writing horror fiction was pushed back into small press imprints, most with poor distribution and close to zero visibility in the marketplace. Writers will keep writing though, and while many of the authors who enjoyed a precarious overnight success during the boom years disappeared from the field (thank God) with equal rapidity, in the pages of the Year’s Best horror anthologies, a new generation of writers were coming to prominence.

Perhaps inevitably, much of the new horror fiction of the early noughties chose to discard the shiny excesses of shopping mall horror, returning instead to older certainties and classic themes. The Elder Gods were much in evidence as writers such as Caitlin R. Kiernan and Laird Barron opened the eyes of a new generation to the vast and eerie possibilities of Lovecraftian cosmic horror. The literature of the ‘bad place’ – the haunted house novel, in other words – also began enjoying a renaissance, and it is here that we begin to see the first manifestations of the horror literature that is now enjoying its own boom in the 2010s and, we would hope, on into the 2020s.

What makes this time different from the last time? I would argue that this new horror is more adult, more serious in intent, and therefore more durable. In their stories of urban decay and alienation, horror writers now are not content merely to reflect social anxiety in their fiction, they want actively to engage with it. Horror archetypes, it seems, are among the most useful and flexible for the purposes of quantifying what is going so badly wrong with the way we live now. But what most differentiates this new horror from the pop horror of the 80s and 90s is, above all, its tenacious sense of place.

The very mention of sense of place lends an impression of solidity, fixedness. We speak also of ‘spirit of place’, a concept infused with the numinous, an identification with the ancient ineffable that writers of the first wave of weird fiction – Machen, Blackwood, Bierce, even M. R. James – would have us believe is somehow ‘in the blood’. Later writers such as Aickman, while masterfully reinforcing the notion that places are strange, also went some way to exploring how slippery and, yes, dangerous such concepts can be, how close to delusion and the kind of mythmaking that foregrounds exclusion and demonises difference. The ground beneath our feet, ironically, has never been as threatened as it is today. As ambient, ever-present anxieties over climate change, plastic pollution, the wholesale destruction of species and ecosystems become – as they should – ever more the substance and spirit of our horror fiction, we should equally remember that our nostalgia for place and time is not bound up with blood, but with personal memory. These places are special to us not because we ‘belong there’ so much as because we were born there, lived there, read stories from there, watched them concrete there over. Which is to say, we all belong wherever there might be, whether we possess an old daguerreotype of our great-great-great-grandparents posed carefully in the living room of the house down the road, or whether we moved in next door only yesterday.

How can we truly belong if we do not protect – which is to say, protect everyone, every species? Even as it is in our nature as writers, humans and chroniclers to cherish our relationship to a particular time and place, to maintain that the arbitrarily defined patch of land we like to call our own is any more ‘special’ than any other is a specious luxury we cannot afford. Even as we croon the old songs, our places are being destroyed. The Elder Gods are close and they are hungry. Horror writers know this. The new horror is a literature not so much of nostalgia as of exposure.

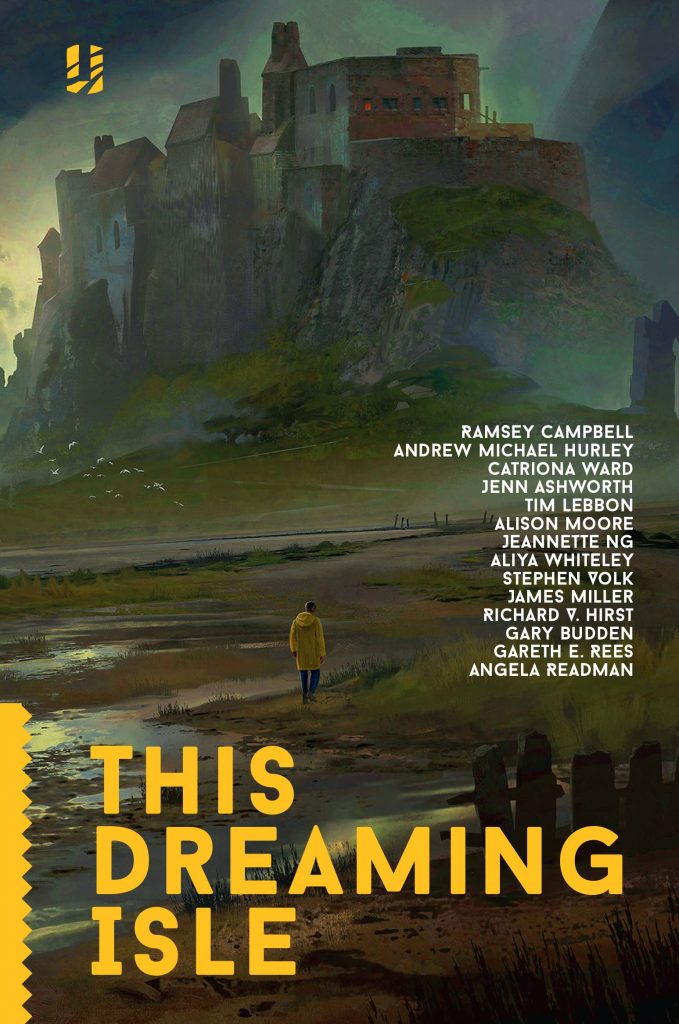

Which brings me, finally, to the point of this essay in drawing attention to a new anthology, which I believe may come to be seen as a landmark in the field. This Dreaming Isle, edited by Dan Coxon for Unsung Stories, brings together a group of writers whose work is intimately concerned not only with sense of place, but with the increasing pressures being brought to bear on our notion of self and belonging – the very concepts that form the core of contemporary horror fiction.

Ramsey Campbell has been writing about this stuff for forty years. A writer who pretty much defines what modern horror is, he was one of the worst affected, in publishing terms, by the collapse of the horror market in the 1990s, yet this has never deterred his output, or damaged his phenomenal ability to plumb the darkest recesses of our crumbling society.

Aliya Whiteley was also hit by shifts in publishing at the beginning of her career. Undaunted, she worked her way back up through the pages of the speculative fiction magazines and anthologies, before publishing two novellas – The Beauty and The Arrival of Missives – that have set a benchmark for quality in new horror fiction and ensured Whiteley’s place as one of the most original voices in the field today.

With the phenomenal success of his debut novel The Loney – a novel of place if ever there was one – Andrew Michael Hurley could be deemed responsible for helping to kick off the new horror boom in the first place. Following closely in his footsteps and with seemingly effortless ease, Catriona Ward has written two back-to-back New Gothic novels rich in geographical specificity, and as good as any that have been published in the past two hundred years. (For more of my thoughts on Cat’s new novel Little Eve, see the next issue of Black Static.) Jenn Ashworth, recently and deservedly named as one of the Royal Society of Literature’s Forty Under Forty, is a phenomenal writer who has never been afraid to utilise horror in talking about class inequality, family, and of course place, while Jeanette Ng, with her 2017 novel Under the Pendulum Sun, has created one of the most imaginative dark fantasy debuts I have ever read, a bold questioning of aspects of faith and belief as well as a provocative and knowledgeable inquiry into the life and work of the Bronte sisters. Co-founder of Influx Press, Gary Budden has been directly instrumental in raising the profile of psychogeography, new weird and strange fiction within a distinctly British context. His own stories, recently showcased in his debut collection Hollow Shores, engage with place, class and memory at a gut level, seeming to morph into something else even as we encounter them.

I would like to reserve a special mention for Alison Moore. Well known in the horror and weird community for some years, Moore was brought to wider public attention in 2012 when her debut novel The Lighthouse was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Her novel appeared on the shortlist alongside Deborah Levy’s Swimming Home, which like The Lighthouse was notable for being published by an independent press. Deborah Levy has since entered the mainstream, a pioneer of the new autofiction and a regular subject of broadsheet author interviews and think pieces. Moore has continued in her own quiet way to produce novels of striking power, originality and literary achievement, but to far less fanfare. I have made no secret of how much it galls me, that Moore has thus far received only a fraction of the appreciation that is her due. To my mind, Moore’s novels are amongst the most assured and potentially durable in English fiction now. Moreover, they are distinctly less London-centric than Levy’s, portraying ordinary people living ordinary lives in a way that reveals how extraordinary we all are, how unstable and unnerving the times – and the places – we live in. Her most recent book, Missing, is her best yet.

These are just some of the writers who have contributed stories to This Dreaming Isle, which is kickstarting now. Fully funded in less than twenty-four hours, the anthology will be officially launched at this year’s FantasyCon in Chester. I’m looking forward to picking up my copy, and would encourage anyone, anywhere who is interested in new horror, folk horror, the strange and the weird to back it now – we want to see those stretch goals met, after all!

For anyone who might be wondering, Dan Coxon did invite me – several times – to contribute to This Dreaming Isle, but in the end I had to decline due to lack of time available. I do have a story half-written that may yet surface at some point in the future. In the meantime I have written this essay, to show how much I wanted to be a part of this project, and to encourage you to be a part of it too. This is going to be good.