“So I sought out others, entirely unlike myself, and when they spoke of secret wisdom, I listened. What men like myself would dismiss as superstition or worse, pure evil, I learned to cherish. The more I read, the more I listened, the more sure I became that a great and secret show had been playing throughout my life, throughout all our lives, but the mass of us were too ignorant, or too frightened, to raise our eyes and watch. Because to watch would be to understand the play isn’t being staged for us. To learn we simply do not matter to the players at all.”

“So I sought out others, entirely unlike myself, and when they spoke of secret wisdom, I listened. What men like myself would dismiss as superstition or worse, pure evil, I learned to cherish. The more I read, the more I listened, the more sure I became that a great and secret show had been playing throughout my life, throughout all our lives, but the mass of us were too ignorant, or too frightened, to raise our eyes and watch. Because to watch would be to understand the play isn’t being staged for us. To learn we simply do not matter to the players at all.”

And so Robert Suydam – the rich and evil genius of the piece – goes on to speak to Tommy Tester – the black Tom of the title – of a King who sleeps at the bottom of the ocean:

“The return of the Sleeping King would mean the end of your people’s wretchedness. The end of all the wreck and squalor of a billion lives. When he rises, he wipes away the follies of mankind. And he is only one of many. They are the Great Old Ones. Their footfalls cause mountains to topple. One gaze strikes ten million bodies dead. But imagine the fortunes of those of us who were allowed to survive!”

Has Robert Suydam not seen Remembrance of the Daleks?? Certainly Tommy is not convinced they should be messing in with all this:

Tommy remained on the porch long after Robert Suydam shut the door. A bright morning in Flatbush, that’s what Tommy saw, but he had a tough time walking down the steps, down the treelined path, and out to the sidewalk. He kept expecting he’d set one foot off the porch and right into an ocean where the Sleeping King waited. And why couldn’t this happen? That’s what paralysed him. If all the rest could be true, then why not so much else?

But with $200 in his pocket, and the promise of $200 more if he returns to Suydam’s mansion the following evening, Tommy finds himself wondering if a second visit might not be in order after all. ‘The old man had been right,’ he acknowledges. ‘Tommy Tester did enjoy a good reward’. And when Tommy returns home to discover that his beloved father has been murdered by the odious detective, ‘Mr Howard’, he begins to see Suynam’s prophecy through new eyes:

What was indifference compared to malice?

“Indifference would be such a relief,” Tommy said.

*

We are in New York in 1924. Tommy Tester is a small-time hustler and musician, getting by the best he can in a world that is predisposed, when it notices him at all, to find him inferior. Tommy knows how to duck and dive though, and with loyal friends and a close relationship with his father, he’s getting by OK. Until the three vectors of his fate – his meeting with Suydam, the death of his father, his theft of a certain piece of notorious arcana – intersect, that is, and Tom realises the world he has been making do with is no longer enough for him.

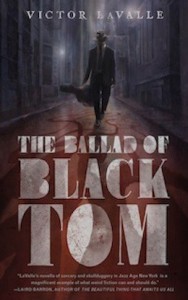

The events and personages of The Ballad of Black Tom are closely modelled upon those of H. P. Lovecraft’s 1925 story ‘The Horror at Red Hook’, and LaValle’s novella is in essence, an impassioned response to that tale, and the seething, furious racism it contains. In Lovecraft’s New York, the eldritch horrors of Parker Place are laid directly at the door of its mainly immigrant population. His story, which is nine-tenths exposition, is an expression of fear and loathing, a certain proof, for any who still need one, of Lovecraft’s bigotry and dis-ease concerning ethnic minorities. LaValle returns Harlem and Red Hook to the people who live there. He makes the protagonist of his story a black man – and if Black Tom ends up a monster, we as readers are left in no doubt as to who has made him one.

In Lovecraft’s story, the detective Malone, like so many of Lovecraft’s protagonists, prefers to look away from what he thinks he has seen. LaValle’s Malone is not given that choice.

There is powerful material here. Tommy’s initial journey out to the mainly white suburb of Flatbush, where his very presence on the train exposes him to personal danger, is a powerful reminder of the violence and opposition faced by African Americans during Lovecraft’s time simply in living their lives. The circumstances surrounding the death of Tommy’s father are particularly devastating when viewed in the knowledge that similarly monstrous injustices are still being perpetrated on a more or less daily basis. Aside from its social and political commentary though, The Ballad of Black Tom should be applauded for making of ‘The Horror at Red Hook’ an actual story. It is a gripping yarn, featuring real characters with real motivations – a claim that can not safely be made for the original tale. That HPL and Sonia make their own cameo appearance is a nice touch also.

What LaValle’s story does not have though is Lovecraft’s language. For all its fomenting lunacy, there is no escaping the fact that HPL’s way with a sentence was something special:

Age-old horror is a hydra with a thousand heads, and the cults of darkness are rooted in blasphemies deeper than the well of Democritus. The soul of the beast is omnipresent and triumphant, and Red Hook’s legions of blear-eyed, pockmarked youths still chant and curse and howl as they file from abyss to abyss, none knows whence or whither, pushed on by blind laws of biology which they may never understand. As of old, more people enter Red Hook than leave it on the landward side, and there are already rumours of new canals running underground to certain centres of traffic in liquor and less mentionable things.

LaValle’s prose, grounded and sound in both mind and body, seems pedestrian by comparison.

*

(Do check out this great interview with Victor LaValle at Electric Literature here, and also this one at SF Signal here.)