When Jane sits back down to her files and notes, we gather around her again, though sometimes she reads too fast for us to follow because even a quick glance at a word like button seller can call to mind a shop with a wall of oak drawers along its length; the smell of the wood polish applied every morning before the doors were opened for business. We see teacher or joiner or clock repairer and suddenly some of us can feel the grit of chalk dust, see holes bored into wood, hear a broken chime drag its heels across the hour – some version of our selves appearing in these notices, a hint of relation, though the details are so scant they don’t make room for the person we were starting to feel we were; someone who may have taken delight in snowfall or a child’s curtsey, the canter of a horse or the efficiency of stamps, or the rough ardour of a washerwoman. These files say nothing of generosity, playfulness, the wing-collared jacket one of us believes he preferred, the bowl of ripe fruit one of us remembers painting in art class, a fly sitting on the leaf of the strawberry. (The World Before Us p 195)

The act of remembering, the action of time upon memory – twin subjects, twin preoccupations, and the central concern of my new novel The Rift, not to mention pretty much everything else I’ve ever written.

The act of remembering, the action of time upon memory – twin subjects, twin preoccupations, and the central concern of my new novel The Rift, not to mention pretty much everything else I’ve ever written.

I remember when my own memory changed. Not the exact day or even the year, but at some point during my thirties I realised that my own past wasn’t available to me the way it once had been. Up until that point, my life appeared to me as a continuous passage, in both the literal and metaphorical senses of that word. I was walking along the passage, occupying the ever-shifting end-point and with only a fraction of a moment’s glimpse into the space beyond the space I currently occupied. But at any time I could, if I chose, turn around and look back down the passage, opening up a vista that encompassed an almost infinite number of moments, all equally fresh, all equally real. In the manner of H. G. Wells’s Time Traveller, I could travel in time through the action of memory. It was an ability I took entirely for granted.

At some point, that changed. Although I was still able to travel back in time, the passage was not continuous, as it had been before. It was as if I’d turned some kind of corner, and now when I looked behind me there was a wall. There was still a door in that wall through which I could pass, but I had to think about it, make a decision, turn a key. The memories behind the door were no longer part of a continuum, but instead had transformed themselves into something else: something more distant, something behind glass, something that could definitively be labelled ‘the past’.

I found this frightening and I still do. More than any physical signs of ageing imposed by time upon my body, it is my most concrete, constant reminder of getting older.

The World Before Us by Aislinn Hunter is one of the most beautifully achieved and penetrating examinations of memory that I have read. Its protagonist, Jane, is a museum archivist who begins to research the disappearance of a young woman, N. from a Victorian mental asylum in the 1870s. This story would be fascinating enough on its own, but Hunter has provided her readers with a delicate tracery of interlinked narratives, threads of memory weaving in and out of one another, a tapestry of knowing. Jane’s interest in the asylum reaches beyond the academic and deep into the personal, for the adjoining woodland where N. went missing was also the site of the traumatic event that defined Jane’s adolescence. Jane is accompanied on her quest by a chorus of ghosts, inmates of the asylum and others closer in time, all bent on recapturing, through Jane’s enquiry, their own memories of who they were and how they came to be there.

I thought at first that I would find Hunter’s ‘ghost chorus’ annoying, an over-ambitious affectation, an imposition of whimsy upon a narrative that would have been just as compelling – and better conceived – without it. I was wrong, though. Hunter handles her ghosts beautifully. They add to, rather than detracting from, the story in hand – their memories form an inextricable part of what is happening to Jane, and one quickly grows used to and looks forward to their presence. Their whispered confidences fuse the novel to a seamless whole.

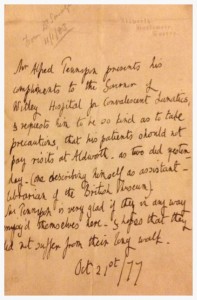

I would probably never have encountered this novel, were it not for this insightful review at Strange Horizons. I loved the sound of the book, and ordered a copy more or less immediately. The copy I ordered was second hand, and turned out to be an advance proof. The cover image is formed by the 1877 letter sent by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, to the governor of a local lunatic asylum and Hunter’s original inspiration for the novel. I found the idea of this proof cover quite beautiful, and wish the publishers had retained it for the final version.

insightful review at Strange Horizons. I loved the sound of the book, and ordered a copy more or less immediately. The copy I ordered was second hand, and turned out to be an advance proof. The cover image is formed by the 1877 letter sent by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, to the governor of a local lunatic asylum and Hunter’s original inspiration for the novel. I found the idea of this proof cover quite beautiful, and wish the publishers had retained it for the final version.

Hunter’s writing in the book about objects, and specific or special objects as touchstones of memory, is especially insightful and to me, driven as I am by similar obsessions, beautiful and moving. Needless to say, my own copy of the book has now become an object-memory in its own right: nearing the end of the novel, I thought I’d go outside to read the last few chapters. I placed the book on the area of concrete hardstanding near our back door while I went to make a cup of tea. While I was doing this, Chris mock-threatened one of our cats with the length of hosepipe attached to the cold water tap next to our log store. The game over, he laid the hosepipe down, and unbeknown to him, a residue of water left in the hose crept out on to the concrete. By the time I returned to my book a few moments later, the water had snaked up to it, soaking the back cover and the last thirty pages right through.

It dried out fine, and the accident was no one’s fault, but it left the book marked, the back cover slightly torn from where it came up off the concrete, the last sixth of the book permanently wrinkled in a wave pattern. I find it sad to look at this damage to what was a beautiful object, but at the same time there’s something magical and almost lucky about it – part of that time, the specific details of that afternoon, captured within a physical object for as long as that physical object itself exists.

I’m kind of glad it happened. I’m very glad I discovered the work of Aislinn Hunter, a writer of true insight and powerful vision. Her prose is quiet but it cuts deep. I loved this book.

(You can read an interview with Aislinn Hunter here. Recommended.)