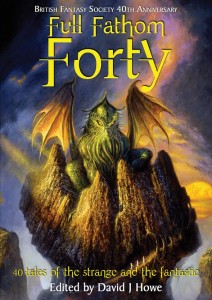

The British Fantasy Society is forty years old this year, and to celebrate, the current chair David Howe has been busy putting together a mammoth forty-story anthology entitled Full Fathom Forty. The book will be launched at this year’s FantasyCon in Brighton. I was surprised and delighted to find one of my own stories, ‘Feet of Clay,’ selected as part of the line-up.

‘Feet of Clay,’ which was originally published last year in the anthology Never Again, edited by Joel Lane and Allyson Bird, had a curious – not to say panic-stricken – genesis. Joel and Ally’s brief was simple: they wanted stories that expressed an opposition to fascism or any other form of racism or hate crime. Not a difficult sentiment to express, you might have thought, and I also believed I had my submission all worked out. As an older child and young adult I adored dystopian fiction. The strong anti-totalitarian message contained in such novels as Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four, Zamyatin’s We, Huxley’s Brave New World and Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day was a positive reinforcement to the idealistic left-wing politics I was dabbling in back then, and I loved the skilfully cadenced call to revolution these stories inspired. The mixture of SF and politics was driving and compelling. More subtle explorations of these themes – Keith Roberts’s magnificent Pavane and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids (possibly my favourite book then and still my favourite Wyndham to this day) made me even more of an addict.

The book that changed everything for me, in a political sense most immediately but in a more far-reaching artistic sense also was Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. It slapped my innocent face with its experience, stunned me with its tensely fought counter-arguments to exactly those questions I had been so devotedly pondering, and – most of all and most importantly – thrilled me with its radical and decidedly European style of engagement with the issues that mattered most to me: freedom of expression and the freedom to decide one’s own fate. What it also showed me – like Orwell’s great novel before it – was how political argument could be voiced in terms of a moving and compelling drama of the emotions.

(It’s a far cry from Chernyshevsky, believe me…… )

What stuck – and sticks – most about the Koestler was its ambiguity. When art is employed in the service of politics of whatever stripe, a dangerous game is being played – dangerous for the politicians (hopefully) and for the artist (certainly). No writer of any worth can ever place himself wholly and one-hundred percent in allegiance with any one party – if he does he’ll find he’s doomed as a writer. For me the ‘simple’ task of writing a story ‘against’ fascism turned out to be hideously difficult. The most obvious pitfall was cliche – it’s all been done before and so much better. Close behind it came the slipperiness of the arguments, the elusiveness of the ‘enemy’ himself: was the death of Heydrich worth the destruction of Lidice? Certainly not. The most obvious means of fighting oppression are rarely the cleverest.

I had decided the best thing to do would be to try my hand at precisely that kind of dystopian tale that had so caught my imagination when I was younger. I took a fragment of something I had tried to write a year or so earlier and turned it into what eventually became ‘The Silver Wind.’ A disastrous decision as it turned out, because Ally and Joel wanted stories of 6,000 words or less; ‘The Silver Wind’ came in at 16,000.

At that point I had precisely two weeks left to meet the deadline. I like to have at least a month to work on a story, and I was in a right panic. In a desperate effort to pull something out of the bag I tried something I’d never attempted before, and wrote the story outwards from the centre. The central scene I had in mind at least was clear to me: a father and a daughter, exploring the hills of the Derbyshire Peak District and talking about a death in the family. That was all I knew at that point, but once I got Jonas and Allis having their conversation it came together. The story even manages to make some points about fascism: not just the horror of its more outrageous crimes, but the insidious ambiguity of its legacy, the Midas-like toxicity of any form of violence, in whoever’s name.

Reading the proofs of the story for Full Fathom Forty I experienced that surge of surprise you occasionally get as a writer when you come upon your work unawares. It was more than a year since I wrote ‘Feet of Clay,’ and I felt glad I had written it.

If the ToC for Full Fathom Forty is anything to go by, this promises to be a book packed with variety and surprise, a genuine ‘snapshot’ of the face of British fantasy in 2011. The only story in the book (apart from my own) that I’ve read thus far is the Rob Shearman, brilliant and brilliantly original as always. The rest I shall have to look forward to along with the rest of you.

For those of you not coming to Brighton, you can pre-order a copy of FFF here