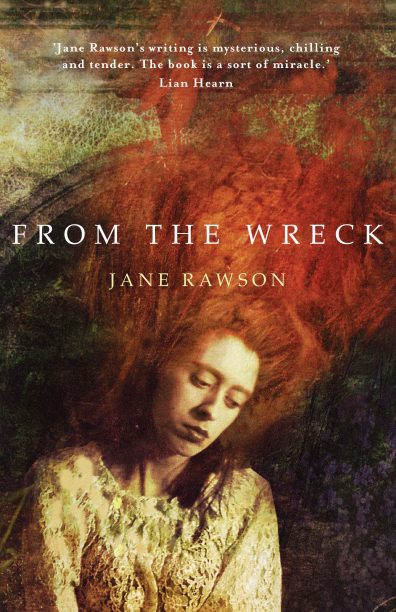

From what I’ve read about her, Jane Rawson would seem to be one of those writers – like Aislinn Hunter, like Claudia Casper – who sometimes struggle to be heard amidst the tumult of overhyped debuts and routine praise for more established voices. Her novels are defiantly uncategorizable – her own debut was named Austrailia’s most underrated book – mixing and leapfrogging genres with scant regard for marketing categories. Well, the good news is that Picador have acquired UK rights to Rawson’s most recent book, the haunting and marvellous speculative novel From the Wreck, making her work available to a wider audience in 2019 and Clarke-eligible in 2020.

From what I’ve read about her, Jane Rawson would seem to be one of those writers – like Aislinn Hunter, like Claudia Casper – who sometimes struggle to be heard amidst the tumult of overhyped debuts and routine praise for more established voices. Her novels are defiantly uncategorizable – her own debut was named Austrailia’s most underrated book – mixing and leapfrogging genres with scant regard for marketing categories. Well, the good news is that Picador have acquired UK rights to Rawson’s most recent book, the haunting and marvellous speculative novel From the Wreck, making her work available to a wider audience in 2019 and Clarke-eligible in 2020.

From the Wreck takes real historical events and bends them to its own ends in a manner I’ve not seen before, an imaginative leap that truly exemplifies the nature of radical speculation. On August 6th 1859, the steamship Admella (named for the ports she regularly sailed between, Adelaide, Melbourne and Launceston, Tasmania) was wrecked on Carpenter Rocks, South Australia. Although multiple efforts were made to reach the stranded survivors, foul weather made a rescue attempt impossible and of the 113 souls on board, only twenty-four ever made it back to shore. One of the survivors, cabin steward George Hills, was Rawson’s great-grandfather. The only woman survivor, Bridget Ledwith, disappeared from public view soon after the tragedy, making her identity a matter of mystery and speculation.

I was personally fascinated to discover that the Admella was built in 1857 by Lawrence Hills & Co, of Port Glasgow, on the Clyde. It is interesting to note that yet another Mr Hills – or more accurately Hill – has a part to play in this story: the painting Wreck of the Admella by Charles Hill hangs in the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

What Rawson does with these established facts – with her own family history – is really quite extraordinary. George Hills returns home after the wreck. Traumatised by his experiences, he finds himself unable to forget the woman who he believes saved his life in the days spent clinging to the remains of the stricken vessel:

“She was a sea creature. He knew that. She had come into the boat from the ocean and she looked and smelled and felt all over like a human woman, but he was damned sure she was not.”

So begins George’s obsessive search for Bridget Ledwith. Yet ‘Bridget’ may be closer to home than he realises. In the shapeshifting alien’s symbiotic relationship with George’s son Henry, other human-alien relationships come swiftly to mind – I was reminded especially of John Wyndham’s Chocky – and yet there is something tender and fragile and edgy that sets Rawson’s work apart:

“And not right then but soon after, when this ocean floor is settled, when all of the fat is gone and the bigger of the things with teeth dispersed, when we’ve remembered that yes it is possible to be even lonelier than you are when you are feeding on wet, rotten fat with the cousins of some crazy lantern-heads, then. When we remember that it is one thing to be in a world all ocean when that world is your own and quite another to be in a world all ocean when no one down there gives a holy damn about you and the only one who does on the whole bereft and stinking planet is some skinnylegged filthy-fingered swollen-hearted little upright on some dusty island up there where the sun is hot and the air is dry, well, then. That’s when we go. Then.”

The three key players in the drama – George, Henry, and the alien – are caught in a strange sort of love triangle that comes close to destroying them all, but the key to this novel is surely its ending, wise and beautiful and blessed because it is earned, arrived at through genuine struggle and personal cost. This is the opposite of the kind of artificially opposed positions we have seen in certain recent works of escapist SF, where real pain and danger are largely absent through being contained within a strictly codified set of markers, and resolution is swiftly arrived at because the conflict was only ever there in the first place to provide the satisfaction of a risk-free resolution. The relationships in From the Wreck are messy and ambiguous, holding the potential for real damage. Rawson’s ending is won through grief, through tragedy, through humility. and love that is as imperfect as it is genuine. From the Wreck provides perhaps the most positive view of humanity in relation to the alien I’ve read in a while, hinting at the innate ability of all parties to transcend boundaries, to learn, to find a safe common ground in spite of mutual ignorance and fear.

Other characters in the narrative are no less well drawn. The character of Bea in particular offers us a wonderful portrayal of a woman who simply will not fit the mould society has prepared for her. Her rebellion and personal victory are quiet yet determined, a refusal to be broken that does not exclude concern for others.

From the Wreck is informed by Rawson’s strong environmental concerns, her deeply sympathetic fascination with other life forms, and above all her sensitivity and skill as a writer, her fearlessness in seeking out new ways to tell stories and new stories to tell. From the Wreck is genuine ‘what if’ science fiction, exploring the possibility of first contact in a manner that does not give humans sole charge of the encounter. Rawson is fully aware that we are the strangers here, that the description of ‘alien’ is only ever a matter of perspective.