On Thursday November 19th I had the pleasure of taking part in a panel presentation and discussion to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the publication of David Lindsay’s novel A Voyage to Arcturus. The event was organised by Dimitra Fimi under the aegis of the University of Glasgow’s Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic and my fellow panellists were the Lindsay and Tolkien scholar Douglas A. Anderson and Professor Robert Davis of the University of Glasgow, who specialises in religious and cultural studies and has a longstanding interest in speculative fiction.

The event was well attended and hugely enjoyable, and ended with the feeling that the discussion could have gone on much longer. I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to everyone involved in making it such a success. Several people have asked me if I could make the text of my personal presentation available through my blog, and so here it is (an appropriate subtitle might be: me making trouble as usual). Thanks once again to Dimitra and the Centre for Fantasy, and here’s hoping our next meeting will be in person.

A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS: A CELEBRATION?

My relationship with A Voyage to Arcturus is a strange one. I first read the novel more than thirty years ago, sometime during the period of my mid-to-late teens, when I was hoovering up science fiction more or less indiscriminately. My memories of it from that time are indistinct – I remember a wandering, quest-like narrative rather in the manner of Jules Verne (his Journey to the Centre of the Earth was one of the first science fiction novels I ever read) only much weirder. I knew nothing about the book’s author, David Lindsay – I had no idea he was Scottish, and I hadn’t realised how much earlier Arcturus had been written than some of the other novels of the fantastic I was reading at the time.

Something of the book’s poetry and mystery must have stayed with me, however, because when I came to write my novel The Rift I knew at once and almost subconsciously that one of its key sections would carry Lindsay’s title. The Rift tells the story of two sisters, Selena and Julie, who are reunited after a separation of twenty years, during which Julie claims to have been living on an alien planet called Tristane. Of course not everyone believes Julie – even her sister is uncertain of whether her account can be trusted – and I think it was this sense of ambiguity around what had happened to Julie that made me remember Arcturus. I was attracted by the poetic synchronicity between my novel and Lindsay’s, the lack of closure around what really occurs. Did the voyage take place, or not? Was it all in the mind? Also I loved the title, just the feel of the words, the chilly elegance of them. I don’t think it’s any accident that when Julie first arrives on Tristane she finds herself in a cold place – the word ‘Arcturus’ was resonating with me even then.

What a surprise to me then when I discovered that A Voyage to Arcturus was not the book’s original title! Lindsay’s working title for his manuscript – some ten years and more in the writing – was Nightspore in Tourmance. His publishers were afraid that sounded too obscure, so encouraged him to change it. A Voyage to Arcturus was first published in 1920 – the same year Isaac Asimov was born, a fact that helps us to remember perhaps just how new science fiction still was as a genre, how original and shockingly outlandish A Voyage to Arcturus must have seemed to readers at the time.

Rereading the novel some three decades after first encountering it, I was immediately struck by how closely Arcturus chimes with the fantastic literature of the age, yet also stands apart from it. Lindsay was known to have read and admired writers like Jules Verne and Rider Haggard as well as his fellow Scots Robert Louis Stevenson and Walter Scott, and their influence is clear: A Voyage to Arcturus is an adventure narrative like no other – its protagonist, Maskull, states from the outset that he is ‘in search of adventure’ – and it’s not hard to find within the narrative echoes of novels such as Ivanhoe, Kidnapped, King Solomon’s Mines and Journey to the Centre of the Earth. But that is where meaningful comparison ends. Although A Voyage to Arcturus might usefully be grouped with science fiction’s early essays in ‘scientific romance’ – the novels of HG Wells being the most obvious example – it is not really like them. Where Wells and Verne style their novels as genuine attempts to imagine or to extrapolate how human society might develop, what wonders and dangers humanity might encounter in exploring the cosmos, the unsolved riddle of our own Earth, even, what Lindsay attempts in A Voyage to Arcturus might be claimed as one of science fiction’s earliest voyages into innerspace.

More even than Wells, I find it interesting to compare Lindsay’s work with Alexei Tolstoy’s 1923 novel Aelita, the first full-length work of Russian science fiction and as important to Russians as Wells’s War of the Worlds is to us Brits. In Aelita, a maverick engineer who has constructed a spacecraft to take him to Mars advertises for a resourceful travelling companion to accompany him on his journey. His eventual comrade is a Bolshevik soldier who is finding it hard to readjust to civilian life in the wake of his experience fighting in the Russian civil war. The metal sphere in which they make their fantastical journey is not at all unlike the crystal torpedo used by Krag, Nightspore and Maskull in their voyage to Arcturus. But whereas Tolstoy uses his scientific romance to further illuminate and explore the harsh ideological landscape of revolutionary Russia, David Lindsay, once again, is doing something rather different.

As Alexei Tolstoy’s experiences in the Russian civil war strongly influenced the writing of Aelita, A Voyage to Arcturus bears the marks and scars of having been written against the bloody backdrop of World War One. If Arcturus could be said to have a central question it could perhaps best be summed up as what makes human existence meaningful, and how do we bear the essential nihilism of a world in which death and suffering are all around? In matters of style and formal approach, there are useful comparisons to be made between the work of David Lindsay and HP Lovecraft. But whereas Lovecraft is obsessed with the terminal nature of everything, the inescapable madness of the howling void, the vision Lindsay offers up is more transcendent than nihilistic. Death comes to all, but in feeling ourselves at one with the universe, in surrendering our selfish desires, we can gain insights into a truer, more spiritual reality, and voyage there without fear.

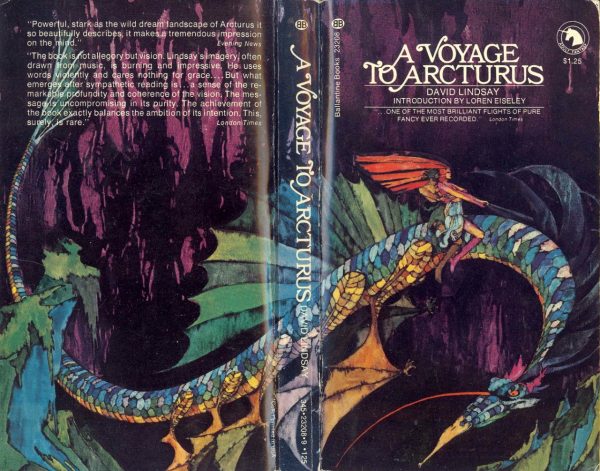

For me, the most successful aspect of A Voyage to Arcturus is Lindsay’s landscape writing. His visions of an alien planet are incandescent, wildly strange and often inspiringly beautiful. The breadth and depth of imagination on display in his descriptions of the terrain, flora and fauna of Tormance, not to mention its people might almost persuade the reader that Lindsay is describing his own dreams.

There is a Wagnerian grandeur to Lindsay’s vision, and I wasn’t entirely surprised to discover that the composer and pianist John Ogdon had written a large-scale operatic composition based on Arcturus, bringing excerpts from the text into consort with passages from the gospels – Ogdon, like others, clearly saw Arcturus as a religious work, somewhat akin to John Bunyan’s A Pilgrim’s Progress, with Maskull in the role of Christian.

Equally fascinating is the new musical adaptation of this impossible novel. Its Australian creator and director, Phil Moore says he was actively drawn to Arcturus because of its philosophical underpinning and because it was ‘a real drama’ as opposed to satire or comedy, in the manner of earlier science fiction musicals like The Little Shop of Horrors or Rocky Horror Picture Show. He has cleverly cast Maskull as a young, attractive, sensitive man as opposed to the pedantic, sexist and peculiarly priggish character we meet in the novel.

For this is where we must ask ourselves how successful, exactly, Lindsay is in his ambition. The cult writer and alternative thinker Colin Wilson was a famous admirer of A Voyage to Arcturus – he called it a masterpiece of the twentieth century – but devotee though he was, he found his patience increasingly tested by what he saw as the stodginess of Lindsay’s style:

The man was a towering genius whose mind is cast in the same mould as that of Dostoevsky… [But] ordinary technical ability, the literary talent that so many third-rate novelists possess in abundance, was denied to him.

As a one-time Russian scholar with a particular interest in Dostoevsky, I found this quote from Wilson enlightening – because it’s not far wrong. Lindsay’s total commitment to and pursuit of an idea – not to say an ideal – is vividly apparent throughout Arcturus. Though his approach is radically different, Lindsay seems to be fired with the same epistemological zeal as the great Russian, and his work likewise offers a vast and tantalising array of possible meanings and interpretations. Dostoevsky though could write character, and did so with passion, as anyone acquainted with Rodion Raskolnikov or Ivan Karamazov would surely attest.

As a novel of character, A Voyage to Arcturus is an embarrassing failure, in which the demands of a simplistic quest narrative are the entire determinant of character action. For me it is not so much the style of Lindsay’s writing that is a problem – Lindsay was possessed of a vivid and singular imagination – so much as its peculiar turn of priggishness and rampant sexism. Lindsay does make some startlingly modern observations about gender and sexuality, even going so far as to invent a set of nonbinary pronouns for one character as he gropes towards a broader understanding of their nature, engaging with these issues in a way that prefigures writing by Ursula Le Guin or John Varley fifty years later.

However there is nothing to explain or excuse the all-round direness of his attitude towards women. In our journey through the landscape of Tourmance we meet Joiwind the angelic helpmeet, Oceaxe the temptress, Tydomin the jealous harpy and Sullenbode, who ‘is not a woman, but a mass of pure sex. Your passion will draw her out into human shape, but only for a moment. If the change were permanent, you would have endowed her with a soul.’

Lindsay has read Nietzche and Schopenhauer and boy it shows. DH Lawrence can get away with a lot when it comes to being a patronising sexist because he’s one hell of a writer. In A Voyage to Arcturus, Lindsay’s prejudices are embarrassingly on display.

Having reread the novel, I would have to frame its relationship to my own novel as ironical. In The Rift, Selena is faced with the choice of believing her sister and cutting herself adrift from her conventional worldview, or clinging to what logic tells her must be the truth and dismissing Julie’s experiences as post-traumatic madness, and I find a renewed satisfaction in the fact that these philosophical arguments are conducted between women – men here are strictly an optional extra. As we turn the final page of Arcturus, we find ourselves faced as readers with a similar dilemma: did any of it happen? Or are we back where we started, on the north east coast of Scotland on a stormy night, wondering why we came here and where we are going?

A Voyage to Arcturus is a singular, frustrating, baffling and ultimately rewarding book – rewarding precisely because of its obscurity, its own inner conflicts and confusion, its refusal to be typecast. It is possibly unique in science fiction, and shines a revelatory light on science fiction’s early development. Once you read it, you may not like it, but you’ll never forget it. I for one will be queuing up to see the musical!