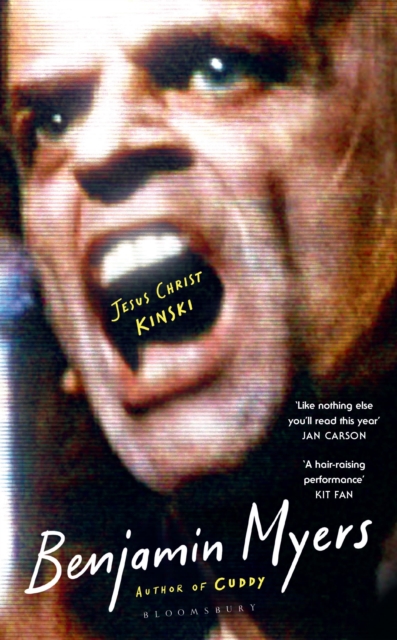

Rock stars, like lunatic actors intent on dominating or destroying every person who crossed their path – including entire film crews in remote jungle locations – were now highly unfashionable relics in an era that placed great value on virtue.

Or, viewed another way, for the first time in a century, children in the Western world had become more boring than their parents.

And did I find myself setting the book aside to take a look at the film? Of course I did. And I was rewarded with something so indisputably out there it is close to hypnotic. And Myers is right in his contention: the closest thing to this kind of outburst we have seen this summer (at a music festival – of course) sees its perpetrators immediately barred from multiple stages, the act itself reduced to a partially deflated political football, batted about the media arena, the meaning behind the words predictably ignored, the mere act of expressing them deemed so scandalous as to be beyond discussion.

The film of Kinski is itself a work of art, the background footage – the cops (grim-faced, arms folded), the promotional flyers, the audience shuffling into the auditorium in their winter coats – is almost equally engrossing, overlaid with a soundtrack of looping, minor-key piano that sounds like a Soviet film soundtrack from the same era. The fashions, the hairstyles, the strange concatenation of an almost forgotten brand of radicalism with terrible dress sense – the queasy unsettlement of being returned with such jarring immediacy to the 1970s.

Myers’s new novel is an essential counterpoint to Ian Penman’s sort-of-autofiction Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors, a still more personal excavation of a particular milieu, a total immersion in both zeit und geist from a writer just that bit further down the road, certain enough of himself not to fall victim to the (almost irresistible, when you’re not only a writer but a British writer, raised in a culture where artists – until officially deemed ‘successful’ and with the trappings to prove it – are regarded with suspicion and hostility as shirkers, routinely condemned for – that ultimate British taboo – ‘getting above themselves’) temptations of self-deprecation in the personal passages.

Thinking about all this one’s mind turns inevitably to what might have happened if Kinski and Fassbinder had been thrown into the lions’ den of working together.

It is clear from the first – the nudges and winks, the catcalls from the further reaches of the auditorium – that the audience are there for a spectacle, for a happening, to see what goes down when things kick off and to expedite that process if necessary. ‘But you have never done any work,’ some would-be agitator yells from the outer darkness. (See what I mean?) A Christian protestor implores those watching to look elsewhere for Christ. And what am I thinking? How come I didn’t stumble upon this brilliant madness sooner? is what I’m thinking, already in danger of being dragged back inside my recurring obsession with the postwar German writers known as Die Gruppe (from whom I have always turned aside from fear of not having a defensible angle because I’m not German, because what I’m running on mainly is instinct, second-hand knowledge, an empathy I can’t explain and therefore can’t claim, although maybe, thinking about it now, the biggest part of my problem is that I’m just too careful) and wondering whether I might dare try digging deeper into Herzog (whose blazing presence I still remember from my time as a bookseller, browsing the Film department, spending hundreds of pounds on glossy monographs before disappearing, far too soon, back into the streetscene) or whether I would do better to set my sights a little lower because how does one say anything meaningful about a genius? (See the lure of self-deprecation, above.)

Myers’s comparing of Kinski with Hitler is a tad predictable, but so what? When Kinski loses it, there’s no way you can’t think of Hitler, it’s almost obligatory, the same as when in pre-2001 movies you catch a glimpse of the New York skyline with the World Trade Center still intact you can’t not think of 9/11. Kinski would most likely not have been thinking of Hitler when he goes crazy but we are. Which is itself worth mentioning, worth putting out there, and surely most of what writing should be is putting it out there. What’s weirdest of all is that Kinski – his lean and hungry look, his rancorous proselytizing, his messiah complex, his raging against the machine – really is much closer to the real Christ than the sanitized, doctrine-burdened icon we’re accustomed to contemplating. Kinski is scratched and dirty and sick, he‘s the Isenheim altarpiece. Jesus wandered in the desert too long and almost lost his mind and this is the result. Truest words: what Myers says near the end about Kinski being lonely. One should judge a man mainly from his depravities. Virtues can be faked. Depravities are real.

Bravo Ben. Bravo Klaus. Bravo, bravo, bravo.